Document 10744590

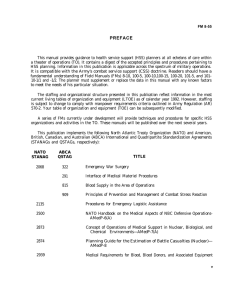

advertisement