Document 10744581

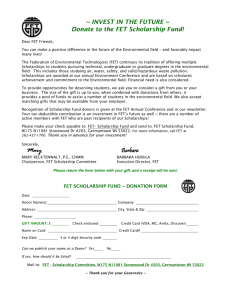

advertisement