Document 10744580

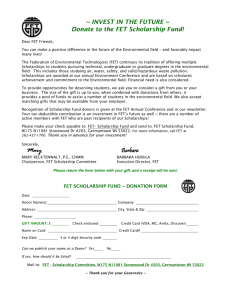

advertisement