Document 10744478

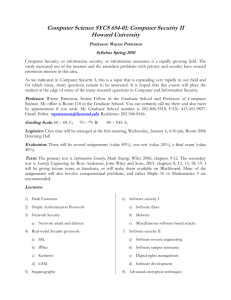

advertisement