In the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit C

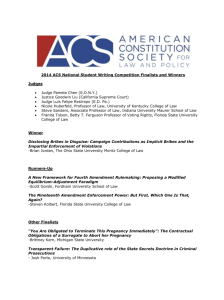

advertisement