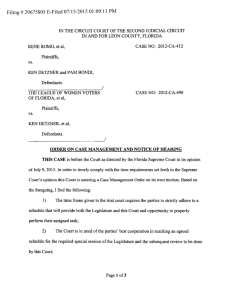

THE LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS et al Plaintiffs,

advertisement