IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL FIRST DISTRICT, STATE OF FLORIDA

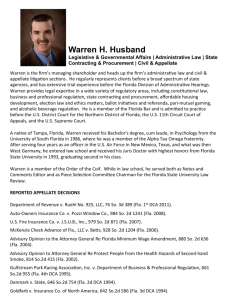

advertisement