IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA THE LEAGUE OF WOMEN et al Appellants,

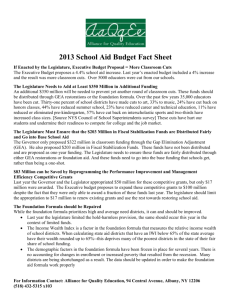

advertisement