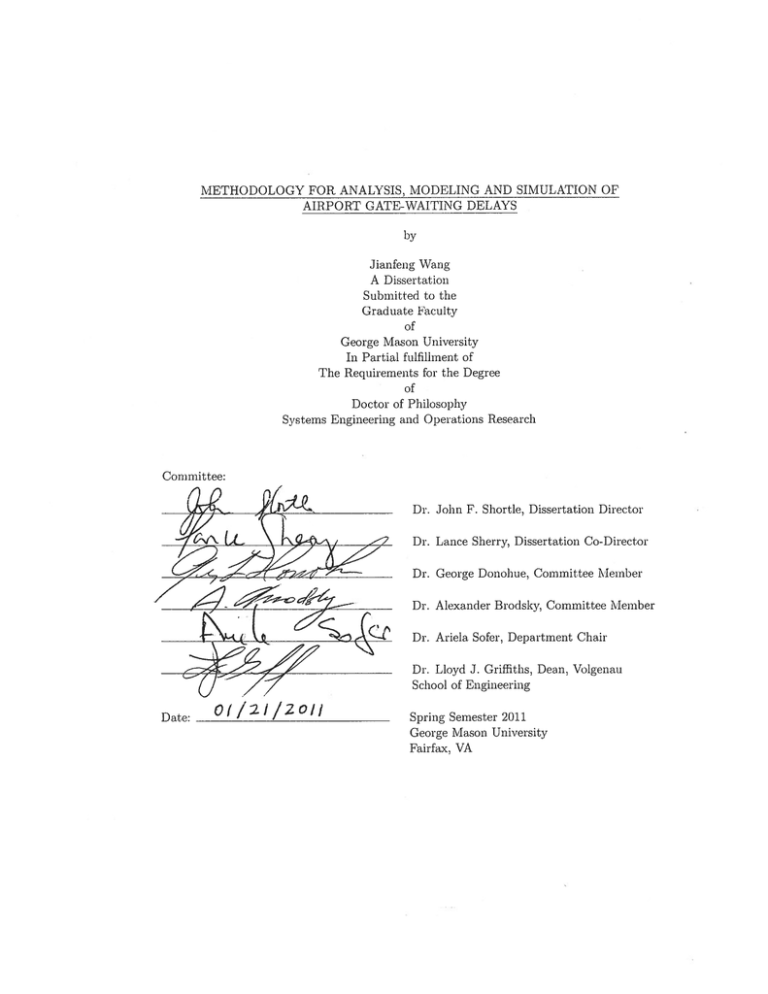

Methodology for Analysis, Modeling and Simulation of Airport Gate-waiting Delays

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University

By

Jianfeng Wang

Master of Science

George Mason University, 2007

Bachelor of Science

Civil Aviation University of China, 2002

Director: Dr. John F. Shortle, Associate Professor

Co-Director: Dr. Lance Sherry, Associate Professor

Department of Systems Engineering and Operations Research

Spring Semester 2011

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA

c 2011 by Jianfeng Wang

Copyright ⃝

All Rights Reserved

ii

Dedication

I dedicate this dissertation to my wife Xiaoxia Tang, my mother Hui Li, my father Bing

Wang, and my grandfather Zhongxue Wang.

iii

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following people who made this possible.

I would like to deeply thank my dissertation director, Dr. John F. Shortle for his tremendous care, encouragement and help on my Ph.D. completion. Dr. Shortle cared very much

for my Ph.D. study. At decision points in my Ph.D. study, the question in Dr. Shortle’s

mind was what would benefit me the most. Dr. Shortle’s encouragement kept me motivated

to complete the dissertation. With Dr. Shortle beside me, I never lost hope no matter how

difficult the situation was. Dr. Shortle offered tremendous help on my Ph.D. study. He

spent lots of time in advising me and thinking for me. He devoted much time to editing

this dissertation. He is very dependable. When I needed help, he always made time for me,

sometimes even over the weekend. After I started working full time, Dr. Shortle tried to

accommodate my schedule. For me, Dr. Shortle is a role model of a first class professor, a

responsible researcher and an integral person. The luckiest thing for me in this journey was

to have him as my dissertation director, and it is a great honor for me having been one of

his Ph.D. students.

I would like to thank my dissertation co-director, Dr. Lance Sherry for his advice, connections, encouragement, and challenges. Dr. Sherry advised me to use a problem-oriented

approach to identify a dissertation topic, to emphasize real world applications, and to use

goal-oriented approach to plan daily activities. Dr. Sherry used his extraordinary capability

to let me connect to many people to find shortcuts to complete the dissertation. For example, Dr. Sherry connected me to Juan Wang on statistics, to Guillermo Calderon-Meza

on database and SQL, to Chris Smith in Sensis Corporation on an algorithm validation, to

David Jacobs on gate operation visualization, to Mike Dupuy on dissertation editing, etc.

When I had challenges and got frustrated, Dr. Sherry often noticed it and offered strong

encouragement with his can-do spirit and bravery. For example, when I was frustrated for

not getting airline data, he told me that data would not be an obstacle. When I saw only a

few people in a conference room to listen to my presentation, he told me that my job was to

present it to one person and to make the person understand. Dr. Sherry also offered tough

questions for me to think more and be better prepared for presentations.

I would like to thank Dr. George L. Donohue’s thought-provoking questions and suggestions to make my dissertation realistic and applicable for policy decisions. His insightful

comments in seminars at the Center for Air Transportation Systems Research (CATSR)

sparked thinking and shaped my view on the air transportation system.

I would like to thank Dr. Alexander Brodsky for helping me to make this dissertation

understandable outside of the aviation community. I especially thank him for improving

my dissertation introduction, background, and conclusion.

I would like to thank Dr. Chun-Hung Chen for offering my first assistantship in the U.S.

so that I could pursuit my Ph.D. at George Mason University (GMU). I also thank him for

teaching me simulation.

iv

I would like to thank fellow CATSR students for helping me in my Ph.D. study. I

would like to thank Guillermo Calderon-Meza for setting up the BTS database server and

Concurrent Versions System (CVS) at CATSR and helping me with SQL programming and

Java programming. I would like to thank Juan Wang for helping me with statistics. I

would like to thank Maricel Medina for helping me with Excel pivot tables. I would like

to thank Abdul Qadar Kara for debugging in Java and recommending CVS. I would like

to thank Raheem Rufai on Java programming and debugging. I would like to thank John

Ferguson on his comments on my presentation slides and checking ATL airport gates for

me in person. I would like to thank Yimin Zhang and Vivek Kumar for their comments on

my presentation slides.

I would like to thank the following people in industry. I would like to thank Chris Smith

in Sensis Corporation for his courtesy to provide JFK airport surface operation videos

in Aerobahn. I would like to thank Dr. Tony Diana and Akira Kondo in the FAA for

providing access to the ASPM databases and help in understanding the databases. I would

like to thank Dr. Terry Thompson in Metron Aviation for his advice on making a good

presentation.

I would like to thank the following GMU graduates, students, and friends. I would like

to thank Dr. Donghai He for encouraging me not to be afraid of working on my Ph.D. while

working full time. He let me work hard such that year 2010 — the last year of my Ph.D.

study and the first year of my professional career — became the most achieving year for

me in life so far. He also helps me technically in many ways, including simulation debug,

LATEX, recommending JabRef to manage references, etc. I would like to thank Dr. Wei Sun

on his advice on Ph.D. study and LATEX. I would like to thank Mike Dupuy for editing my

dissertation.

I would like to thank my supervisor at CSSI, inc., Melissa Ohsfeldt, who always encourages team members on continuing education and publishing papers and is flexible with

work schedule.

Finally, I would like to thank my family for their support and influence. I thank my wife

Xiaoxia Tang, who keeps supporting me to accomplish this goal from September 2004 to

February 2011 despite my limited economic and time contribution to the family in this long

journey. I also appreciate her reminding me to stay focused on my study from distractions.

I thank my mother Hui Li, who encourages me to work hard when young, to be brave to

face difficulties, and to respect any work I do. I thank my grandfather Zhongxue Wang,

who provided me with pre-school education and cultivated my interest in natural science.

I learned from him to be truthful to the work I do and to be truthful as a person.

v

Table of Contents

Page

List of Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

List of Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

List of Abbreviations . . . . . . .

Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1 Introduction . . . . . . . . .

1.1 Airport Gate Congestion

.

.

.

.

xiv

xv

1

2

Problem Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.2.1 Research Objectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

6

1.2.2

Research Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

1.3

Unique Contributions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

1.4

Summary of Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

1.5 Potential Readers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2 Background and Literature Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9

10

1.2

2.1

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Airport Operations and Gate-waiting Delays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10

2.1.1

The Gate Assignment Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10

2.1.2

2.1.3

Gate Arrival Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Turnaround Operations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13

13

Related literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.1 Gate-waiting Delay Metric . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

14

2.2.2

Gate-waiting Delay Functional Causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

2.2.3

Gate-waiting Delay Mitigation Strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

2.2.4

Relationship Between Gate, Taxiway and Runway Capacity . . . . .

22

Summary of Key Gaps in the Literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

Data Sources and Algorithms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

3.1

Data Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.1.1 BTS Airline On-Time Performance Database . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.1.2 ASPM Individual Flights Database and Taxi Times Database . . . .

25

25

26

3.1.3

26

2.2

2.3

3

.

.

.

.

ix

xi

Comparison of BTS and ASPM Databases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

vi

3.2

3.3

4

3.2.1

Modeling of Taxi-in Process and Gate-occupancy Process . . . . . .

30

3.2.2

Algorithm 1: Estimation and Validation of Gate-waiting Delay . . .

31

3.2.3

Algorithm 2: Estimation of Gate Occupancy Time . . . . . . . . . .

33

Key Limitations and Assumptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

. . . . . . . . . . . .

36

Gate Delay Characteristics at Major U.S. Airports . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

4.1.1

Gate Delay by Airport . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

4.1.2

Gate Delay by Day . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

4.1.3

Gate Delay by Time of Day . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

4.1.4

Gate Delay by Carrier . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

4.1.5

Gate Delay by Aircraft Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

Functional Causes of Gate Delay in High Gate Delay Days . . . . . . . . . .

47

4.2.1

Analysis of Carrier Aggregated Data (6 Airports) . . . . . . . . . . .

49

4.2.2

Analysis of Carrier Specific Data (LGA) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

Analysis Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

4.3.1

Average Gate Delay Across the OEP-35 Airports . . . . . . . . . . .

63

4.3.2

High Gate-Delay Days at Six Major Airports . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

Gate Delay Simulation Model and Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

65

5.1

Gate-delay Simulation Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

5.1.1

Scope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

5.1.2

Terminology

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

5.1.3

Model Description and Data Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

69

5.1.4

Modeling Assumptions and Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

5.1.5

Implementation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

Simulation Results and Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

5.2.1

Canonical Airport Simulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

5.2.2

5.2.3

5.2.4

5.2.5

LGA Simulation . . . . . . .

ATL Simulation . . . . . . .

DFW Simulation . . . . . . .

Simulation Results Summary

.

.

.

.

88

92

94

98

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.1 Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.1.1 Gate Delay Severity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

102

102

102

4.2

4.3

5.2

6

28

30

Gate-waiting Delay Characteristics and Functional Causes

4.1

5

3.1.4 Other Data Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Algorithms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

vii

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

6.2

6.1.2

Gate Delay Characteristics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

102

6.1.3

Gate Delay Functional Causes

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

103

6.1.4

Gate Delay Mitigation Strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

103

Future Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.2.1 Improved Gate Delay Modeling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

103

103

6.2.2

104

Industrial Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A Functional Cause Identification of Extreme Gate Delays Using Carrier Aggregated

Data (BTS Data) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

106

A.1

A.2

A.3

A.4

A.5

A.6

A.7

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

B Simulation Model Source Code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

113

169

LGA . . . . . . . . .

ATL . . . . . . . . .

JFK . . . . . . . . .

EWR . . . . . . . .

DFW . . . . . . . .

MIA . . . . . . . . .

6 Airport Summary

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

viii

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

List of Tables

Table

Page

3.1

Coverage of BTS and ASPM databases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

3.2

Flights recorded in various data sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

3.3

Required parameters and data sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

3.4

Results for arrival departure pairing, ATL, summer 2007, BTS data . . . .

34

4.1

Scope of the analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

4.2

Top 10 airports (if available) which have high gate-waiting fraction flights,

Algorithm 1b . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.3

Gate-waiting delay by major carriers at several major U.S. airports, Algorithm 1a (ASPM data) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.4

41

46

Gate-waiting delay difference between major carriers, three major airports

in the New York, Algorithm 1a (ASPM data) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

4.5

Pearson correlation coefficients between gate-waiting delay and aircraft size,

4.6

ASPM data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Specific days analyzed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.7

Gate Delay Functional Causes in 12 High Gate-delay Days at LGA in Summer

59

5.1

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Deterministic simulation model parameters and assumptions illustrated with

LGA, part 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

5.2

48

55

Deterministic simulation model parameters and assumptions illustrated with

LGA, part 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

71

5.3

Stochastic simulation model parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

72

5.4

Demand disaggregation, fictitious data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

76

5.5

Disruption: one factor at a time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

83

5.6

Eight factors to be investigated, canonical airport (one carrier) . . . . . . .

86

5.7

One factor at a time for disruption and factorial design for mitigation strategies 87

5.8

Calculated mitigation effects on disruptions, canonical airport . . . . . . . .

89

5.9

Eight factors to be investigated, LGA (AA, MQ, DL, OH) . . . . . . . . . .

91

ix

5.10 Calculated mitigation effects on disruptions, LGA

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

93

5.11 Impact of common gates on gate delay reduction; disruption: arrival delay,

LGA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

94

5.12 Eight factors to be investigated, ATL (DL, FL) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

95

5.13 Calculated mitigation effects on disruptions, ATL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

96

5.14 Impact of common gates on gate delay reduction; disruption: gate-blocking

time extension, ATL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

5.15 Eight factors to be investigated, DFW (AA, MQ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

99

5.16 Calculated mitigation effects on disruptions, DFW . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

100

A.1 Functional Causes of High Gate Delay in the Worst 3 Days at LGA in Summer

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.2 Functional Causes of High Gate Delay in the Worst 3 Days at ATL in Summer

106

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.3 Functional Causes of High Gate Delay in the Worst 3 Days at JFK in Summer

107

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.4 Functional Causes of High Gate Delay in the Worst 3 Days at EWR in

108

Summer 2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.5 Functional Causes of High Gate Delay in the Worst 3 Days at DFW in

109

Summer 2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.6 Functional Causes of High Gate Delay in the Worst 3 Days at MIA in Summer

110

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.7 Gate Delay Functional Causes in 18 High Gate-delay Days in Summer 2007

111

112

x

List of Figures

Figure

Page

1.1

Loop of aircraft phases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

1.2

Gate waiting at penalty box at Chicago O’Hare airport . . . . . . . . . . .

3

1.3

High gate-delay-fraction days in OEP-35 airports, summer 2007, Algorithm

1b (will be discussed in Section 3.2.2) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

2.1

Chronological issues related to gate delay . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

2.2

Gate assignment GUI (an arrow represents a flight; a color represents an

aircraft type) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

2.3

Functional causes of gate-waiting delay . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

2.4

Gate delay mitigation strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

3.1

Delta and Northwest terminal and five remote gates at LGA. The fact that

Comair’s Gate 5A has no jet bridge or contact gate parking and that two

regional jets park at the remote gates indicate that Comair uses the five

remote gates; Source: Google Maps snapshot on 7/6/2009. . . . . . . . . . .

29

3.2

Taxi-in and gate-occupancy process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

3.3

Algorithm 1a: gate-waiting-delay estimation only using ASPM database . .

32

3.4

Algorithm 1b: gate-waiting-delay estimation primarily using BTS database

33

3.5

Arrival and departure pairing method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

4.1

Gate delay per scheduled fight in OEP 35 airports, summer 2007, Algorithm

4.2

1b . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Gate-delay fraction in OEP 35 airports, summer 2007, Algorithm 1b . . . .

4.3

Gate delay per scheduled fight in OEP 35 airports, summer 2007, Algorithm

4.4

40

1b . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

High gate-delay-fraction days in OEP-35 airports, summer 2007, Algorithm 1b 40

4.5

Rough gate/runway capacity ratio at some major U.S. airports . . . . . . .

42

4.6

Gate-waiting delay by day at ORD, Algorithm 1b . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

43

4.7

Daily gate delay of high gate-delay airports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

44

4.8

Gate-waiting percentage by time, Algorithm 1b (BTS data) . . . . . . . . .

45

xi

38

39

4.9

Scatter plot of gate-waiting delay in minutes by number of seats at EWR,

Algorithm 1a (ASPM data) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

4.10 Comparison of daily total gate delay and schedule volume, ATL and LGA,

summer 2007, BTS data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

4.11 Functional cause identification, ATL, 06/11/2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

4.12 Functional cause identification, ATL, 07/29/2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

52

4.13 Functional cause identification, LGA, 06/27/2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

4.14 Cancellations on 4 days, ATL, BTS data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

4.15 Daily gate-waiting delay and QQ plot against gamma model, summer 2007

57

4.16 Total gate-waiting delay by time of day and carrier, LGA . . . . . . . . . .

58

4.17 Gate usage of American and American Eagle, LGA, 6/27/2007 . . . . . . .

60

4.18 Comair gate-waiting delay, arrival rate at LGA on 8/9/2007 . . . . . . . . .

61

4.19 Gate delay and gate-occupancy time by time of day (actual gate-in time),

American and American Eagle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

5.1

Gate delay functional causes and mitigation strategies . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

5.2

Critical times in gate operation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

5.3

The remote gate area at Washington Dulles International Airport . . . . . .

69

5.4

5.5

Simulation model overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Simulation model demand input, LGA data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

73

74

5.6

Demand disruption A: arrival delay; start hour: 19, duration: 2 hours; arrival

delay: 3 hours; fictitious data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.7

75

Demand disruption B: regular turn gate-blocking time extension; start hour:

19, duration: 2 hours; gate-blocking time extension multiplier: 2; fictitious

5.8

data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Demand disruption C: regular turns converted to ending turns; start hour:

75

19, duration: 2 hours; fraction of regular turns converted to ending turns:

0.5; fictitious data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

76

Simulation model supply disruption and mitigation; LGA data . . . . . . .

77

5.10 Canonical airport demand profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

5.11 Canonical airport gate occupancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

82

5.12 Impact of disruptions: one factor at a time, canonical airport . . . . . . . .

83

5.13 Impact of demand disruption A: arrival delay; canonical airport . . . . . . .

84

5.9

5.14 Impact of disruptions (AA, MQ) on total daily gate delays (AA, MQ, DL,

OH): one factor at a time, LGA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

xii

90

5.15 Impact of disruptions (DL) on total daily gate delays (DL, FL): one factor

at a time, ATL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

5.16 Impact of disruptions (AA,MQ) on total daily gate delays (AA,MQ): one

factor at a time, DFW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

A.1 Gate delay functional cause identification at LGA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

106

A.2 Gate delay functional cause identification at ATL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

107

A.3 Gate delay functional cause identification at JFK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

108

A.4 Gate delay functional cause identification at EWR . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

109

A.5 Gate delay functional cause identification at DFW . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

110

A.6 Gate delay functional cause identification at MIA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

111

xiii

List of Abbreviations

ASPM

Aviation System Performance Metrics

ATC

Air Traffic Control

BTS

Bureau of Transportation Statistics

FAA

Federal Aviation Administration

NAS

National Airspace System

NextGen

Next Generation Air Transportation System

OEP

Operational Evolution Plan

OOOI

Out of the gate, Off the ground, On the ground and Into the Gate

ASQP

Airline Service Quality Performance

ARINC

Aeronautical Radio, Incorporated

xiv

Abstract

METHODOLOGY FOR ANALYSIS, MODELING AND SIMULATION OF AIRPORT

GATE-WAITING DELAYS

Jianfeng Wang, PhD

George Mason University, 2011

Dissertation Director: Dr. John F. Shortle

Dissertation Co-Director: Dr. Lance Sherry

This dissertation presents methodologies to estimate gate-waiting delays from historical

data, to identify gate-waiting-delay functional causes in major U.S. airports, and to evaluate

the impact of gate operation disruptions and mitigation strategies on gate-waiting delay.

Airport gates are a resource of congestion in the air transportation system. When

an arriving flight cannot pull into its gate, the delay it experiences is called gate-waiting

delay. Some possible reasons for gate-waiting delay are: the gate is occupied, gate staff

or equipment is unavailable, the weather prevents the use of the gate (e.g. lightning), or

the airline has a preferred gate assignment. Gate-waiting delays potentially stay with the

aircraft throughout the day (unless they are absorbed), adding costs to passengers and the

airlines. As the volume of flights increases, ensuring that airport gates do not become a

choke point of the system is critical.

The first part of the dissertation presents a methodology for estimating gate-waiting

delays based on historical, publicly available sources. Analysis of gate-waiting delays at

major U.S. airports in the summer of 2007 identifies the following. (i) Gate-waiting delay

is not a significant problem on majority of days; however, the worst delay days (e.g. 4%

of the days at LGA) are extreme outliers. (ii) The Atlanta International Airport (ATL),

the John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), the Dallas/Fort Worth International

Airport (DFW) and the Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) experience the highest

gate-waiting delays among major U.S. airports. (iii) There is a significant gate-waitingdelay difference between airlines due to a disproportional gate allocation. (iv) Gate-waiting

delay is sensitive to time of a day and schedule peaks.

According to basic principles of queueing theory, gate-waiting delay can be attributed to

over-scheduling, higher-than-scheduled arrival rate, longer-than-scheduled gate-occupancy

time, and reduced gate availability. Analysis of the worst days at six major airports in the

summer of 2007 indicates that major gate-waiting delays are primarily due to operational

disruptions — specifically, extended gate occupancy time, reduced gate availability and

higher-than-scheduled arrival rate (usually due to arrival delay). Major gate-waiting delays

are not a result of over-scheduling.

The second part of this dissertation presents a simulation model to evaluate the impact of

gate operational disruptions and gate-waiting-delay mitigation strategies, including building

new gates, implementing common gates, using overnight off-gate parking and adopting selfdocking gates. Simulation results show the following effects of disruptions: (i) The impact

of arrival delay in a time window (e.g. 7 pm to 9 pm) on gate-waiting delay is bounded. (ii)

The impact of longer-than-scheduled gate-occupancy times in a time window on gate-waiting

delay can be unbounded and gate-waiting delay can increase linearly as the disruption level

increases. (iii) Small reductions in gate availability have a small impact on gate-waiting

delay due to slack gate capacity, while larger reductions have a non-linear impact as slack

gate capacity is used up.

Simulation results show the following effects of mitigation strategies: (i) Implementing common gates is an effective mitigation strategy, especially for airports with a flight

schedule not dominated by one carrier, such as LGA. (ii) The overnight off-gate rule is

effective in mitigating gate-waiting delay for flights stranded overnight following departure

cancellations. This is especially true at airports where the gate utilization is at maximum

overnight, such as LGA and DFW. The overnight off-gate rule can also be very effective

to mitigate gate-waiting delay due to operational disruptions in evenings. (iii) Self-docking

gates are effective in mitigating gate-waiting delay due to reduced gate availability.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Growth in demand for air travel has outstripped the growth in capacity provided by airports

and the Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSP). In 2007, flight delays cost passengers

and airlines $12 to $14 billion in lost time and fuel [Robyn, 2008]. In 2010, nationwide air

traffic congestion is predicted to cost $46 billion to the nation’s economy [FAA, 2009].

Air passenger traffic is forecasted to double in 15 years and triple in 20 years with

an expected yearly growth rate of 5 percent [Yeamans, 2001]. To meet growing demand,

aircraft manufacturers have developed the A380 ‘super-jumbo’ jet that will be capable of

carrying from 555 to 800 passengers, and the Next Generation Air Transportation System

(NextGen) is designed to increase the capacity of the national airspace system (NAS), while

increasing efficiency and safety through the use of leading edge technology by using satellites

for navigation and communication [JPDO, 2007].

Currently, the capacity of the air transportation system is limited by airport capacity in

the U.S. [Dillingham, 2005] and airports will continue to be a primary element in the total

capacity of the air transportation system [JPDO, 2007, chapter 3, page 5]. Airport capacity

is affected by many factors such as the configuration and geometry of the airport, the

organization and procedures for airspace use (i.e., air traffic management), airport operating

procedures (i.e., how the runways are used), airmanship, and technology. Of prime concern

to the air transport system are the adequacy of the runways to handle the number of aircraft

movements and the adequacy of the number of terminal gates to load and unload passengers

and cargo. If the runway capacity or the terminal gate capacity is inadequate, delays will

occur [McGregor, 2004]. “Runway capacity at the busiest airports is the primary limiting

factor in NAS operations today, and even with the maximum possible efficiency gains,

some airports may need additional runways to accommodate the expected traffic growth.

1

Focus of this research

Gate queue

Travel starting

and ending point

Takeoff queue

Landing queue

Research scope

Figure 1.1: Loop of aircraft phases

Implementing super-density arrival/departure procedures enables closer spacing for arrivals

and departures and new runways can be built much closer to existing runways” [JPDO,

2007, chapter 2, page 18]. The secondary major limiting factor is the number of gates at an

airport [McGregor, 2004]. In enabling NextGen, one important component is “the reduction

of ground movement delays and congestion due to constrained airport infrastructure” by

“providing sufficient gate capacity” [JPDO, 2007, chapter 3, page 26].

1.1

Airport Gate Congestion

As an airplane arrives to and departs from an airport, it passes through several potential

choke points. These include arrival and departure paths, runways, taxiways, ramps, gates,

and so forth (Figure 1.1 shows a notional illustration). Depending on the demand and

number of resources, different points in this process may become constrained and act as a

choke point. For example, after an aircraft lands on a runway, there are scenarios in which

it cannot pull into its assigned gate and must sit on the tarmac to wait. This phenomenon

is defined as gate waiting. Several airports have created space for flights to “park” if their

assigned gates are not available. This space is known as the “penalty box”. Figure 1.2

shows the penalty box at Chicago O’Hare airport [Matt, 2005].

Studies have identified the stages of flight in which delays occur and the causal factors

that result in delays. For example, the Department of Transportation [Mead, 2001] classifies

delays as turnaround delay, taxi-out delay, airborne delay and taxi-in delay. Taxi-in delay

2

Penalty box

Figure 1.2: Gate waiting at penalty box at Chicago O’Hare airport

accounts for about 8% of overall delay [Mueller and Chatterji, 2002], and gate-waiting

delays (gate delay for short) are the dominant contributor to taxi-in delays [Idris et al.,

1999, Gosling, 1993].

Figure 1.3 shows the gate-waiting severity at the U.S. OEP-35 airports1 in the summer

of 2007. (The specific algorithms used to generate these results will be discussed in Section 3.2.2.) The dark bars in the graph, show the number of days during which 30% or more

of the flights experienced a gate-waiting delay in the summer of 2007. Out of the 35 major

airports, 10 had at least one such day; the other 24 airports did not have any such days, so

they are not shown on the x-axis. The lighter bars in the graph show the number of days

during which 30% or more of the flights experienced gate-waiting delay and pulled into the

gate after the scheduled arrival time. Flights that experienced gate-waiting delay due to

early arrival, but ended up arriving at the gate on time, are not counted. DFW, ATL, JFK

and PHL have the most days during which 30% or more of the flights experienced a strictly

positive gate-waiting delay. On average, 66% of these days in the three airports were due

to early arrivals, representing padding in the schedule and inflexibility/inability to change

1

commercial U.S. airports with significant activity [FAA, 2007]

3

60

50

40

Number of days

Early arrivals

30

30% or more flights experience gate waiting

30% or more flights experience gate waiting

and arrive later than scheduled

20

10

0

DFW

JFK

PHL

ATL

MSP

LGA

IAH

MIA EWR LAX

Airport

Figure 1.3: High gate-delay-fraction days in OEP-35 airports, summer 2007, Algorithm 1b

(will be discussed in Section 3.2.2)

gate assignments when early arrivals occur.

Gate delays affect airline operations and scheduling in many ways. First, gate-waiting

delay increases the cost of operating a flight, including fuel burned, crew cost, aircraft life

and engine life. Second, gate-waiting delays may have a propagation effect due to aircraft

turnaround and crew and passenger connections [Xu, 2007]. If the airport is the passenger’s

final destination, the passenger’s trip delay is equal to this flight’s arrival delay. However,

if gate-waiting delay causes passengers to miss their connections, the passenger’s trip delay

can be much higher than the arrival delay [Wang, 2007, Sherry and Donohue, 2009]. Third,

an airline’s schedule is limited by gate availability. For example, AirTran was not able to

add new flights at ATL until 2007 when three new gates were added [Ramos, 2007].

Gate delays affect an airport’s attractiveness to carriers. Gate availability is a prerequisite to attract new entrant carriers and to expand operations of existing carriers [Belliotti,

2008, page 30].

Gate delay can also affect the FAA Air Traffic Control (ATC)’s surface operations if

airports do not have enough space to hold aircraft waiting for a gate. For example, Boston

Logan International Airport (BOS) does not have holding pads where aircraft can wait for

4

gates, so held aircraft may contribute to surface congestion [Idris et al., 1999].

Gate delay can cause severe customer service problems. Being “trapped on a plane for

several hours causes a lot of frustration” [Stoller, 2009]. In January 1999, severe gate delays

of Northwest Airlines flights at Detroit in stranded hundreds of passengers on aircraft queued

on taxiways for up to 8.5 hours [Slater, 1999]. On August 8, 2009, Continental Airlines and

ExpressJet Airlines caused the passengers on board Continental Express flight 2816 to

remain on the aircraft at Rochester International Airport for almost 6 hours [DOT, 2009a].

In November 2008, the Department of Transportation proposed a rule to enhance airline

passenger protections, including a provision that requires airlines to adopt contingency plans

for lengthy tarmac delays and incorporate them in their contracts of carriage [DOT, 2009a].

New consumer rules prohibit U.S. airlines operating domestic flights from permitting an

aircraft to remain on the tarmac for more than three hours [DOT, 2009b].

Early identification of potential gate congestion is important to take proactive approach.

Atlanta airport has been historically gate constrained. Until 2007, it had not added gates

since building the international E concourse prior to the 1996 Olympics [Ramos, 2007]. After

its 5th runway was commissioned in 2006, gate constraints emerged as a bottleneck [Terreri,

2009] and three new gates were finally added in 2007 [Ramos, 2007]. However, the three new

gates are not enough to meet demand and have become “a sore point between the airport

and its two hub airlines, Delta and AirTran” as both airlines seek the gates’ exclusive use2 .

The severe gate constraint was not realized until the fifth runway was commissioned. After

high gate delay occurred, a reactive approach was taken to implement surface management

system and to assign common gates [Terreri, 2009]. The gate delay could have been better

mitigated if these processes were started earlier.

As the volume of aircraft increases in the national airspace system, ensuring that airport

gates do not become a choke point of the system is critical.

2

The airport finally assigned them as common use [Ramos, 2007]

5

1.2

Problem Statement

Research on gate delay is limited and insufficient due to limited data availability and rarity

of severe gate delays.

Many researchers refer to the gate-waiting phenomenon [Idris, 2001, Richards, 2008].

But most existing research on gate delay is limited to anecdotes [Slater, 1999], experience

or qualitative analysis [Gosling, 1993]. Few quantitative metrics have been given on the

percentage of gate delay as a cause of taxi-in delay [Idris et al., 1999]. NextGen’s concept of

operations “examines concepts that can advance the capabilities of existing infrastructure

and enable new infrastructure to be developed as needed,” but do not identify or intend

to identify specific locations for gate needs at existing airports [JPDO, 2007, chapter 3,

page 1].

No methodology has been developed to identify functional causes of system-wide gate

delay. Systematic analysis of functional causes of severe gate delay is limited because

severe gate disruptions are rare [Slater, 1999]. Mitigation strategies of gate delay have

been suggested individually, but their impacts have not been compared quantitatively or

evaluated collectively.

1.2.1

Research Objectives

The objectives of this research are as follows.

1. Estimate the severity of gate delay at major U.S. airports. The objective is to evaluate

the degree to which airport gates are a limiting resource in the flow of airplanes arriving

to and departing from an airport.

2. Investigate characteristics of gate delay (e.g. effects of carrier, aircraft type, time

of day, etc.). The objective is to determine how gate delays are distributed across

different carriers, aircraft types, and time, etc. For example, it is possible that gate

delays are a problem only for local to specific carriers, in which case gate exchange

among carriers would be helpful.

6

3. Identify functional causes of gate delay. The objective is to consider the system as a

queueing system where airplanes are users and gates are servers. According to queueing theory [Gross et al., 2008], waiting time is a function of arrival (runway landing)

patterns, service (gate occupancy) patterns, number of available servers (gates), and

the queueing discipline (first-come-first served, priority, etc.). The objective is to

identify which of these functions contributes most to the worst gate delays.

4. Evaluate mitigation strategies on gate delay. The objective is to compare different

gate-delay reduction initiatives and investigate how effective these strategies are in

dealing with gate delay under different functional causes.

1.2.2

Research Approach

To achieve the four objectives, the following approach is adopted:

1. Develop a set of unique algorithms based on publicly available data to:

(a) Estimate the gate delay of each arriving flight;

(b) Estimate the gate occupancy time of each turn;

(c) Construct aggregated hourly arrival rate, average gate occupancy time, and gate

utilization;

2. Build a gate-delay simulation to evaluate mitigation strategies of different scenarios:

(a) Develop a stochastic process-based discrete event simulation queueing model to

simulate aircraft movements through gate system;

(b) Construct disruption scenarios based on historical analysis;

(c) Conduct experiments of disruption scenarios with mitigation strategies;

(d) Conduct an experimental design to rank factors and interactions between them

by effects on gate delay.

7

1.3

Unique Contributions

There are three major contributions of this dissertation:

1. This research develops a systematic method for analysis of gate-delay severity and

characteristics. Gate-delay comparison across different airports can be used to identify

specific locations of airport development needs. The asymmetry of gate delay across

airlines can be used by airports for decision making on airline gate allocation and

common gate reservation.

2. This research develops a systematic method to identify functional causes for severe

gate delays.

3. This research develops a gate-delay simulation model, which enables researchers to

evaluate the impacts of major gate-delay functional causes and mitigation strategies

collectively. For example, the simulation can be used to answer questions like, “How

do common gates mitigate gate delay compared with adding new gates?” The model

can also be used to predict gate congestion beyond historical boundaries.

1.4

Summary of Results

This dissertation shows the asymmetry of gate delay across different airports, carriers, days

and time of day. Airports with the biggest gate-delay problems in 2007 were ATL, JFK,

DFW and PHL. There are significant gate delay differences between carriers as a result

of disproportional gate allocation. On most days, gate delays are minor and do not limit

throughput through the airport. However, the worst days tend to be extreme outliers.

Observed severe gate delays were always related to operation disruptions, rather than

over-scheduling. Disruptions include higher-than-scheduled arrival rate, longer gate occupancy time and reduced gate availability. Among the 18 worst days in the summer of 2007,

higher-than-scheduled arrival delay occurred in 9 days, longer gate occupancy time occurred

in 10 days, and reduced gate availability occurred in 10 days.

8

Use of common gates can mitigate gate delays effectively, especially for airports that

are not dominated by a small number of carriers, such as LGA. Overnight off-gate parking

can be effective in mitigating gate disruptions in evenings, especially at airports where gate

utilization is at maximum overnight, such as DFW. There are diminishing returns in the

use of multiple mitigation strategies.

1.5

Potential Readers

Airlines can use this research to assist with the decision on flight cancellations and aircraft

swapping — a process that often ignores gate constraints and delays. In addition, airlines

can use this research to make decisions on gate exchange with other airlines, as well as

investment on new gates/stands and automatic docking systems.

Airports can use this research to gain insights of gate utilization and to assist policy

decisions regarding common gates and gates allocation to airlines. The FAA can use this research to identify specific locations for airport development needs, considering runway/gate

capacity expansion and departure/arrival operation management.

9

Chapter 2: Background and Literature Review

This chapter reviews existing literature related to gate delay. Section 2.1 describes airport

operations related to gate delay. Section 2.2 reviews research related to gate-waiting delays.

Section 2.3 summarizes the key gaps in the literature.

2.1

Airport Operations and Gate-waiting Delays

Gate delay occurs when a flight cannot pull into its gate and must therefore wait on

the tarmac. This phenomenon is closely related to gate assignment, gate arrival process,

turnaround process, etc. Figure 2.1 shows the chronological issues related to gate delay.

2.1.1

The Gate Assignment Process

Gate-waiting delay is closely related to gate assignment, the process of assigning flights to

gates. Gate assignment is usually handled in three phases [Bazargan, 2004].

Phase 1: Feasibility Check

The first phase is a long term planning effort which occurs several months before the day

of operation. Ground controllers check that a feasible gate assignment can be made with

the proposed flight schedule, without making an actual gate assignment. A gate assignment

planning tool (similar to what is shown in Figure 2.2) can be used to give an overall sense

of the gate assignment plan. The schedule must be changed or reduced if there are not

enough gates (except for over-scheduling).

10

Airports (sometimes with airlines): Terminal

building and common gate allocation

(sometimes exclusive gates allocation)

(usually years before operation)

Possible issue: over-scheduling,

schedule padding (quick response to

market)

Airlines: publish schedule

(about 3 months before operation)

0:00

Gate 1

Gate 2

Gate 3

……

Gate n

3:00

6:00

Possible issues: sub-optimal gate allocation

to carriers and common gate reservation

(slow response to market)

12:00 15:00 18:00 21:00 24:00

Airlines: make initial gate assignment

(hours before operation, say 4 am on the

operation day)

Airlines / NAS / ATC: land aircraft (operation)

Airlines: dock aircraft at gate (operation)

Possible issue: not enough buffer

time between two consecutive turns

to absorb operation disruptions (early

arrivals, late departures)

Possible issue: arrival disruption (land

early and no gate, land late and depart late,

arrival cancellation)

Possible issues: gate occupied, ground

crew unavailable (manpower, weather),

inflexible gate change policy

Airlines: turn around aircraft (operation)

Airlines: push back (sometimes needs ATC

clearance or considers ATC information)

ATC: sometimes hold aircraft at gate or other

areas at an airport (operation)

Possible issue: cancellation, flight crew

shortage, ground crew shortage, gate

hold due to GDP

Figure 2.1: Chronological issues related to gate delay

0:00

3:00

6:00

12:00 15:00 18:00 21:00 24:00

Gate 1

Gate 2

Gate 3

……

Gate n

Figure 2.2: Gate assignment GUI (an arrow represents a flight; a color represents an aircraft

type)

11

Phase 2: Development of Daily Gate Assignment Plan

The second phase involves development of a single-day plan prior to the start of the actual

day of operation. A gate assignment tool, similar to the planning tool, can be used to get

the initial gate assignment plan at the start of the day, or the initial gate board.

This phase is the main focus of research on gate assignments. The objective is to improve

the performance of initial gate assignments. The problem is usually modeled as an integer

program [Haghani and Chen, 1998, Yan and Huo, 2001], a mixed integer program [Bolat,

1999, Bolat, 2000] or a network flow problem [Yan and Chang, 1998, Yan and Tang, 2007].

Due to uncertainty in the input data driving the gate assignment process, the gate

assignment tool must be designed such that it produces solutions that are robust to uncertainty. Certain input parameters related to resource demand, such as the expected landing

time and the expected pushback time, are difficult to predict prior to these events [Roling

and Visser, 2007]. A gate assignment planning tool must therefore be able to adapt to perturbations in these input conditions, as well as to account for taxi-in delay due to taxiway

congestions. Adding a buffer time usually improves robustness, but it is still a heuristic

approach constrained by gate capacity.

Phase 3: Change of Gate Assignment During Operation

The third phase revises these daily plans throughout the day of operation due to irregular operations such as delays, bad weather, mechanical failures and maintenance requirements [Bolat, 2000]. The same gate assignment tool can be used to create the initial gate

board at the beginning of the day (phase 2) and to update the gate assignment throughout

the day (phase 3). These updates affect gate waiting, and hence flight on-time performance,

as well as airport staffing and passenger relocations. The updates are made based on gate

controllers’ experience sometimes with the assistance from computer algorithms.

Some models have been developed to focus on gate changes [Gu and Chung, 1999, Yan

and Tang, 2007]. In addition, some research has evaluated the relationship between the

initial gate assignment plan and the real-time gate changes necessary to meet the stochastic

12

flight delays that occur in real operations [Yan et al., 2002, Yan and Tang, 2007, Dorndorf

et al., 2007].

2.1.2

Gate Arrival Process

When an aircraft lands on a runway, it usually goes straight to the ramp (with possible

taxiway delay) and pulls into its assigned gate. In some cases, an aircraft is unable pull

into its gate and is obliged to hold on the tarmac to wait, due to gate unavailability, ground

personnel unavailability, or other causes. The aircraft may stay on the ramp, penalty box,

inactive taxiway, or inactive runway to wait. Generally, it is preferred to park the aircraft in

a non-movement area to minimize disruption to taxiway and ramp operations. For example,

Boston Logan International Airport (BOS) uses hangar positions to store aircraft that do

not have a gate readily available [Idris, 2001]. Chicago O’Hare airport uses a penalty

box to park gate-waiting aircraft temporarily [Matt, 2005]. New York John F. Kennedy

International Airport (JFK) uses inactive taxiways (based on observation of Sensis Taxiview

video1 ).

2.1.3

Turnaround Operations

After arriving at the gate, an aircraft usually goes through a turnaround process to disembark passengers and embark passengers. The turnaround operation includes passenger deplaning and boarding, fueling, and other activities [Fricke and Schultz, 2008]. The

turnaround operation has been mainly investigated using the Critical Path Method (CPM)

[Braaksma and Shortreed, 1971, Idris et al., 1999, Wu and Caves, 2003, Fricke and Schultz,

2008] to study operational procedures consisting of several work flows in order to identify

critical paths in the operation, including passenger flow, crew, catering, fueling, luggage,

cleaning, maintenance, etc.

After the turnaround operation, an aircraft may continue occupying its gate until its

planned departure time to conform to its schedule or its destination airport capacity limit

1

http://www.sensis.com/docs/261/, accessed on Oct. 2, 2010

13

(Ground Delay Program). However, when its gate is requested by another aircraft, this

flight may be pushed back to wait on the tarmac for runway departure.

2.2

Related literature

Research related to this dissertation can be categorized into the following areas:

1. Gate-waiting delay metrics

2. Gate-waiting delay functional causes

3. Mitigation strategies of gate-waiting delay

4. Relationships between gate, taxiway and runway capacity

2.2.1

Gate-waiting Delay Metric

Researchers have mainly described the gate-waiting delay phenomenon anecdotally [Slater,

1999, DOT, 2009a] or by experience [Gosling, 1993, Stoller, 2009, Richards, 2008]. Gatewaiting delay is considered to be the largest contributor of taxi-in delay [Gosling, 1993].

Metrics have been developed to quantify the severity of gate-waiting delay in several major airports. The Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS)

records delay duration and cause based on voluntary pilot reports [Idris et al., 1999, Idris,

2001]. Percentages of total delays by cause show that, for Dallas/Fort Worth International

Airport (DFW), Chicago O’Hare International Airport (ORD) and Boston Logan International Airport (BOS), there is a dominance of the taxi-in delays due to gate congestion (gate

occupied) over the other delay categories, such as ramp and field congestion [Idris et al.,

1999]. Based on an analysis by the Department of Transportation [Mead, 2001], taxi-in

delay accounts for about 8% of overall delay [Mueller and Chatterji, 2002].

To date, the author is not aware of any system wide analysis of gate delay using quantitative metrics.

14

Estimation and

characteristics

Functional causes

Stroller 2009

Idris 2001

United 2007

Gate Delay

Factors

•Airport

•Day

•Time

•Carrier

•Aircraft size

Idris 2001

Idris 2001

Gross et al. 2008

Bazargan 2004

Over-scheduling

Higher Arrival Rate

Lower Service Rate

Idris 2001

Richards 2008

Idris 1999

United 2007

Lower Gate Utilization

Waiting time

λ 0(t )

→1

µ 0(t )c 0

1

λ(t)

µ(t) ⋅ c(t)

λ (t ) > λ 0(t ) λ (t ) : Arrival rate

µ (t ) : Service rate

µ (t ) < µ 0(t ) c(t ) :

No. servers

c(t ) < c 0

Figure 2.3: Functional causes of gate-waiting delay

2.2.2

Gate-waiting Delay Functional Causes

Gate-related delays can be understood according to concepts in queueing theory [Gross

et al., 2008], where arriving flights can be thought of as “customers” and gates as “servers”.

Generally speaking, congestion in queueing theory is determined by the utilization quantity,

ρ(t) = λ(t)/c(t)µ(t), where λ(t) is the arrival rate at time t, c(t) is the number of servers

at time t, and µ(t) is the service rate of each server at time t. Higher values of ρ(t)

correspond to greater congestion. Flight operations are based on a schedule where the

scheduled utilization quantity is ρ0 (t) = λ0 (t)/c0 µ0 (t), where λ0 (t) is the scheduled arrival

rate at time t, c0 is the nominal number of servers, and µ0 (t) is the scheduled service rate

of each server at time t. There are four functional causes for gate delay, over-scheduling

(ρ0 (t) is already high (approaching 1)), higher-than-scheduled arrival rate (λ(t) > λ0 (t)),

lower-than-scheduled service rate (µ(t) < µ0 (t)), and reduced available gates or reduced

utilization (c(t) < c0 ), as shown in Figure 2.3.

Over-scheduling can result in gate-waiting delays [Stoller, 2009]. For example, some

airlines over-scheduled their gates at Boston Logan Airport and consequently had more

aircraft on the ground than the number of available gates [Idris, 2001]. Typically, airlines

schedule gates for only up to 80% occupancy, knowing that they will need reserve capacity

to deal with random occurrences [Horonjeff and McKelvey, 1993].

15

High aircraft arrival rates and long gate occupancy times (compared with scheduled

operations) can also be a reason for gate-waiting delay. When an arrival flight finds its

gate occupied, it may be because the arrival aircraft is early; however, it is often due to the

departure delay of its previous flight assigned to the same gate [Idris, 2001].

Gate delay can be also be caused by a reduced number of usable gates, which can

be caused by a variety of reasons, including awaiting gate assignment, unavailable ramp

staff or ground equipment, inclement weather [Idris et al., 1999, Richards, 2008] and airline

preference for keeping the original gate assignment. Based on communication with a gate

manager of a major airline, this particular airline usually lets an arriving aircraft wait for its

original assigned gate even if there is an open alternative, when the gate conflict is detected

late. The reason is that last minute gate reassignment requires crew and passengers on

the ground to be redirected with short notice. Another scenario for the preference of using

the original assigned gate is for early landings, when the itineracy of the aircraft, the crew,

and the passengers are not disrupted by gate delay, as long as the gate arrival is on time.

Generally, the original assigned gate is preferred unless the expected gate-waiting delay is

too long.

2.2.3

Gate-waiting Delay Mitigation Strategies

To deal with different functional causes of gate delay, different strategies2 can be used to

mitigate gate delay as follows (also see Figure 2.43 ):

1. Increase gate capacity (increase c0 ),

2. Reduce scheduled gate occupancy time (increase µ0 ),

3. Reduce scheduled flight volume (reduce λ0 ),

2

One strategy directly mitigates the impact of one particular functional cause. However, the strategy

may indirect mitigate the impact of other functional causes.

3

Strategies in grey color are less recommended because these strategies have large adverse effects or their

effects are not direct.

16

Estimation and

characteristics

Functional causes

Gross et al. 2008

Bazargan 2004

Stroller 2009

Idris 2001

United 2007

Mitigation strategies

JFK Jetblue 2008

ATL 2011

Fricke 2008

Airline: reduce gate

occupancy time

Steuart 1974

Airline: under-schedule

Over-scheduling

Le 2006

Gate Delay

Factors

•Airport

•Day

•Time

•Carrier

•Aircraft size

Idris 2001

Idris 2001

Higher Arrival Rate

Lower Service Rate

Manley 2008

Richards 2008

Reduced

Idris 1999

United 2007

Gate Availability

FAA: runway slot control

ATC: traffic flow

management

Slater 1999

Airline: arrival cancellations

Wang 2010

Airline / airport: off-terminal

parking

Neufville 2002

Idris 2001

Idris 2001

Airline / airport : more gates

Richards 2008

Gu 1999,

Yan 2002,

Yan 2007,

Dorndorf 2007

Airline / airport : common gates

Airline / airport: self-docking

gates

Airline / airport: gate

reassignment

Figure 2.4: Gate delay mitigation strategies

4. Use traffic flow management, such as Ground Delay Program (GDP) to slow runway

arrivals (reduce λ),

5. Cancel arrivals (reduce λ),

6. Tow aircraft off-gate (increase µ),

7. Use common gates (may increase c),

8. Use self-docking systems to improve gate reliability (increase c),

9. Improve gate assignment algorithms (increase c).

Mitigation Strategies for Over-scheduling

To deal with over-scheduling, the key is to reduce gate demand relative to gate capacity.

There are three basic strategies: Increase the number of gates (c0 ), reduce the scheduled

gate occupancy time (1/µ0 ), and reduce the scheduled number of flights (λ0 ).

The first strategy is to increase gate capacity, that is, to increase c0 . If there is a big

imbalance between demand and capacity, this is the only way to meet demand. Of course,

17

this is expensive and limited by the land at airports. Gates have two forms, contact gates

and remote gates.

Contact-gate capacity expansion usually requires terminal expansion because the gates

need to be built with terminals. For example, on October 22, 2008, JetBlue opened its new

Terminal 5 at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) at the cost of approximately

$800 million. The new terminal has 26 gates and can handle 500 daily departures and

arrivals, almost twice the 270 flights the airline used to operate at JFK [Maynard, 2008]. At

ATL, the new international terminal is projected to feature 12 new international gates with

a projected delivery in 2011, at a cost of $1.4 billion [Tharpe, 2008]. Another new terminal

scheduled to be completed after the new international terminal, featuring 70 additional

domestic gates, is estimated to cost around $1.8 billion [Garrett, 2005].

Remote gates are used to park the aircraft remotely on hardstands and transport passengers via buses or vans to the concourses and terminals. However, such operations — already

being used at many airports to avoid the expense of terminal and apron expansions — have

proven to be quite expensive operationally. This arrangement is also inconvenient for passengers and service crews [Yeamans, 2001].

A key question is how many gates are needed since flights do not always arrive and

depart on time. Stochastic models have been developed to model the uncertainty of arrival

punctuality and aircraft gate occupancy time [Hassounah and Steuart, 1993,Wu and Caves,

2003]. Hassounah and Steuart [Hassounah and Steuart, 1993, Steuart, 1974], Edwards and

Newell [Edwards and Newell, 1969], and Bandara and Wirasinghe [Bandara and Wirasinghe,

1988] use empirical data to predict gate demand under uncertainty.

The second strategy is to reduce the scheduled gate occupancy time, that is, to reduce

(1/µ0 ) or increase µ0 . Gate occupancy time is commercially lost time and is therefore

desired to be as short as possible. Gate-occupancy-time reduction can be achieved through

turnaround reliability improvement using second jet-bridges, innovative boarding concepts,

auto adjustment for conveyer belts and equipment, etc. The Single European Sky Air

Traffic Management Research (SESAR) project has set the performance target to cut gate

18

occupancy time for short/medium range aircraft from around 30 minutes currently down

to 15 minutes in 2020 [Fricke and Schultz, 2008].

The third strategy is to reduce the scheduled flight volume, that is, to reduce λ0 . Airline

under-scheduling and reserving spare gates for operation disruption can effectively control

gate congestion [Steuart, 1974, pages 169–189]. The FAA’s slot control may also reduce gate

demand by limiting the number of landings allowed in an airport [Le, 2006]. The scheduled

flight volume should be capped by both gate constraints and runway constraints, whichever

is more restrictive.

Runway capacity is more of a concern to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA),

whereas gate capacity is more of a concern to airlines. For an airport where runway capacity

is more restrictive, if the scheduled arrival volume from airlines is higher than the runway

capacity, the FAA may impose runway slot controls to reduce delay. Once the demand for

runway is capped, the demand for gates is capped accordingly. See Section 2.2.4 for research

on the relationship between runway and gate capacity. The disadvantage of reducing flight

volume is that this measure may decrease airline revenue.

Mitigation Strategies for Higher-Than-Scheduled Arrival Rate

Gate delay can result from higher-than-scheduled arrival rate due to stochasticity in flight

operations. Air Traffic Control (ATC) can be impacted because a higher arrival rate may

require aircraft holding or lead to gridlock on the airport taxiway system. Another strategy

to reduce gate delay is to use traffic flow management, such as Ground Delay Program

(GDP) to slow runway arrivals, that is, to reduce λ.

NextGen’s Trajectory Management has the prospect of better schedule compliance by

assigning each arriving aircraft to an appropriate runway, arrival stream, and place in sequence [JPDO, 2007, chapter 2, page 21]. In addition, a higher-than-scheduled arrival rate

can result from early arrivals, usually a result of schedule padding. Trajectory Management’s promise for better arrival time prediction may encourage airlines to remove some

schedule padding and hence mitigate gate delay.

19

Another strategy is to cancel arrivals, that is, to reduce λ. If the gate-waiting delay

is so large that too many arrival flights are stranded on tarmac for gate during severe

operation disruption, airlines can cancel arrival flight to reduce gate demand. This approach

is only needed in very rare occurrences when huge gate delay is anticipated. For example,

DTW experienced a snowstorm in Jan. 2–4, 1999 and airline operations were disrupted.

Many airlines cancelled their arrival flights. However, Northwest airline failed to realize

the gate congestion and kept operating inbound flights to DTW and a huge gate delay

occurred [Slater, 1999].

Mitigation Strategies for Longer-Than-Scheduled Gate Occupancy Time

Gate delay can result from longer-than-scheduled gate occupancy time. Longer gate occupancy time is either a result of longer-than-scheduled gate service time, or a result of gate

holding caused by downstream restrictions (discussed in Section 2.2.4). One strategy is to

tow aircraft off-gate4 in order to reduce the time the aircraft occupies a gate, 1/µ [Wang

et al., 2010]; however, towing leads to airlines’ increased operating cost.

Mitigation Strategies for Reduced Available Gates

Another strategy to reduce gate delay is to share gates among airlines, which may increase

c for individual airlines. Two primary drivers that motivate the use of shared gates are

peaking of traffic at different times and uncertainty in the level or type of traffic [de Neufville

and Belin, 2002]. Some gates in airports are reserved for common use for the ease of exchange

of gate usage between different airlines [Ramos, 2007]. Some airports do not have reserved

common gates, but can force gate exchanges when needed. At Boston Logan Airport, the

limited gate capacity problem is made worse by the inflexibility of the airlines to exchange

the use of gates with each other. The Mass-Port Authority (MPA), which maintains Logan

Airport, can force such an exchange when an airline is underutilizing a gate, especially

for international flights, which have a limited number of gates in Terminal E [Idris and

4

mainly for aircraft having a long turnaround time, such as flights staying at an airport overnight

20

Hansman, 2000].

Then the next question becomes “What percentage should be allocated for common

use?” According to integer programming, the fewer the constraints, the better the optimal

solution could be. So all common use could achieve the best gate utilization and lowest gate

delay possible. However, airlines prefer exclusive gate usage for their predictable planning

and efficient operation. So some percentage of gates should be exclusive to specific airlines.

There is also a third form, called preferential use, meaning one airline has preference to use

a gate, but if it is not used, other airlines can use it. This form had been proven ineffective.

“The greater the proportion of common and exclusive-use gates the greater the reduction in

inefficiency5 . Common use gates means the airport controls gate use and will ensure they

are used most efficiently. Similarly, when a gate has been given to a carrier for exclusive

use, it is in the carrier’s best interest to use the resource efficiently. As the proportion

of preferential-use gates rises, efficiency falls. A carrier that has preferential treatment

may try to use gates as a barrier to entry and not necessarily use them efficiently.” [Gillen

and Lall, 1997]. Ideally, the airport should reserve a certain fraction of gates as common

use to account for uncertainty and individual carriers’ peak traffic only. Then individual

carriers can schedule their gates to full capacity. This fraction could be a function of time

of day since uncertainties later in the day are usually higher. The fraction could also be

a function of weather forecasts which predicts the uncertainty level on a day to day basis.

Steuart [Steuart, 1974] used queueing theory to estimate the fraction of gate capacity that

should be reserved for unscheduled extra needs due to delays and other random events. The

key finding is that the fraction decreases when the number of scheduled gates is larger (this

is because random effects tend to cancel when there are more gates) [de Neufville and Belin,

2002]. The limitation of research in common gates is that the research is mainly focused on

small operation perturbations, instead of major operation disruptions.

If gate delay is because aircraft wait to dock in inclement weather or ramp staff is

unavailable, self-docking systems can improve gate reliability (increase c) and reduce gate

5

Terminal efficiency was defined as number of passengers and pounds of cargo served given number of

runways, number of gates and other airport resources.

21

delays. Self-docking systems use laser-based technology to allow pilots to self-park at the

gate, without the need of a ramp worker to marshal it into its gate position. The system has

already been implemented for 92 of 157 gates at Dallas/Forth Worth International Airport

(DFW) since January 2008 [Richards, 2008].

If gate delay is a result of an airline’s reluctance to change gate assignment at the last

moment, one strategy to reduce gate delay is to use more efficient gate assignment algorithms to effectively increase the number of usable gates, c. Algorithms were developed to

improve gate assignment robustness in planning and reduce gate idle time in operation, as

mentioned in Section 2.1.1. But there are three limitations in this research area. First,

gate changes are usually undesirable. A gate change with a long lead time, say 4 hours in

advance, is not so problematic. But a short lead time, say 30 minutes, may be problematic.

Previous research neglected this fact. Second, research in robust gate planning has typically considered small stochastic delays in the schedule and not major disruptions. This

dissertation shows that major schedule disruptions can have a significant impact on gate

congestion, and corresponding gate assignment strategies need to be developed for these