Modesto Bee, CA 11-13-07 MISTAKEN IDENTITY

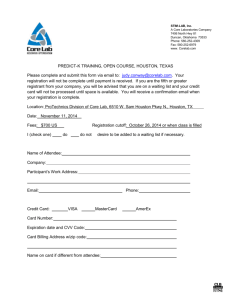

advertisement

Modesto Bee, CA 11-13-07 MISTAKEN IDENTITY An innocent man spent weeks in jail after the Modesto victim of an attempted robbery id'd him. But the victim was wrong. By EMILIE RAGUSO eraguso@modbee.com Richard Houston Jr. left his house in northwest Modesto one cool August night heading for a party. By morning, he had been arrested on suspicion of armed robbery after a victim said he was "100 percent sure" Houston was his assailant. The victim was wrong. Houston spent nearly two months in jail. The Stanislaus County district attorney's office dropped the charges against Houston a day after Deputy District Attorney Nate Baker watched a surveillance tape from a store where the victim saw the gunman before the crime. Houston, Baker determined, could not have been the robber. No one else has been arrested. "I felt reborn when I walked through the gate," said Houston, 20, about his release from the Stanislaus County Public Safety Center. Houston splits his time between Modesto, where his stepmother lives, and his father's home in Stockton. "I spent 55 days in jail. That time's double when you're in there for nothing." Law enforcement officers stress that most arrests are good. Houston's arrest, however, illustrates the risks of eyewitness identification. Mistaken eyewitness identifications contributed to more than 75 percent of the 208 wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence in the United States since 1989, according to the Innocence Project, a nonprofit legal clinic at the Cardozo School of Law in New York City. Eight of the nine California exonerations relied on eyewitness identification. Psychologists who study memory say it isn't as reliable as most people, including police and prosecutors, assume. "We put more faith in eyewitness identifications than we should," said Daniel Reisberg, a professor of cognitive psychology, perception and memory at Reed College in Portland, Ore. He testifies in court as an expert in these areas. "Juries put a lot of faith in eyewitness identifications. They're the second most powerful form of evidence, with first place going to a confession. They're next in line as the best way to persuade a jury." 'Empty your pockets' Sometime before 2 a.m. on Aug. 15, a 45-year-old man left his home near Cheyenne Way and Prescott Road in Modesto to buy cigarettes at Stop N Save Liquors. The man's name has been withheld at his request. About 2:20 a.m., while walking home from the market at 1701 Standiford Ave., he heard noises in the bushes. Two people stepped onto the sidewalk. "Empty your pockets," said one, wearing a hat, a white mask, a white shirt and dark pants. The other was wearing dark clothing and a dark mask. Both were black, the victim said, in their 20s and about 6 feet tall. He recognized the gunman as someone he'd seen at Stop N Save. "I start screaming, 'Help!' I see a gun pointing at me," the victim said. "I don't know if these people will shoot or not. All these things are going through my mind fast." He ran south on Carver and flagged down a police officer. Nearby, at 2:22 a.m., Modesto police Sgt. Ed Steele heard a broadcast about the robbery attempt, according to his police report. Steele drove north on Prescott from Standiford to look for suspects. Houston had watched TV for most of the day at his stepmother's house Aug. 14, a Tuesday. About 1 a.m. Wednesday, his best friend, Angel Mota, called to see whether Houston wanted to hang out. About 2 a.m., Houston left his stepmother's home, near Standiford and Prescott, to walk to Mota's, just north of Pelandale Avenue off Prescott. As he walked, Houston talked on his cell phone to a friend who told him about a party off Tully Road. Steele was on Prescott when he saw Houston: a black man in a cap, white shirt and dark pants walking north on Prescott near Snyder Avenue. The description of the gunman matched the man walking, according to Steele. Houston was coming from the direction of the crime and Steele said Houston jumped over a wall when Steele was following him, which Houston denies. Steele said he watched Houston run to a house on Floral Court, which turned out to be Mota's, then called for backup. Police took extra precautions because a handgun had been used in the robbery attempt. Houston said he had seen a police officer following him but thought the officer had driven away. He walked out of Mota's front door when his friend, waiting to pick them up, asked whether Houston could see all the police outside. Houston found guns drawn on him; he was handcuffed and placed in a police car. Officers did not tell him why they stopped him, he said. Officers brought the victim to Mota's. They held spotlights on Houston while they pulled his shirt up over his nose and his cap down over his eyes. Police told the victim that Houston might not be the assailant and that there was no pressure to identify him. This disclaimer, called a Simmons Admonishment, is required during "field show-up" identifications like this, said police Sgt. Craig Gundlach. The victim told police he was sure Houston was the man who tried to rob him. Police took Houston to the station and arrested him within a few hours. "When Houston came out, the guy fit almost exactly who I saw," the victim said last week. "I was pretty certain. I was as close to certain as I could be that he was one of the assailants." The eye is not a camera Popular models of human behavior, which posit that the eye is a camera and that memory is a tape recorder, are simply incorrect, said psychologist Robert Shomer, a former instructor at Harvard and now a consultant in Southern California. "It's completely bogus. The fact of the matter is that people's faces are nonimperishably stored. Memory is very dynamic and changeable," he said. Just showing a victim a suspect can change a person's memory of his attacker. Field show-ups are particularly problematic, because the victim is viewing someone in handcuffs, surrounded by police, usually within an hour of the crime. "Once you run a person through a suggestive eyewitness identification process (such as a field show-up), you've altered the evidence irretrievably. There is no mental eraser." Field show-ups used to be universally reviled by researchers because of the suggestive atmosphere, said psychologist Reisberg, but recent studies have found that victims also tend to be more cautious about making identifications during them. "It's hard to maintain the claim that across the board it's a bad procedure," he said. Many factors can influence how well witnesses remember. High levels of stress, for example, have been shown to make it harder to recall an event accurately. A 2004 study on more than 500 military personnel found that subjects who underwent high-stress interrogations were much less likely, 24 hours later, to be able to identify their interrogators than those whose sessions did not include the risk of violence. "Weapon focus" also plays a major role. Repeated studies have found that people are much more likely to remember an assailant's face if no weapon was present during an attack. The weapon is like a "visual magnet," said psychologist Shomer, drawing attention from its wielder. Accurate memory of an attacker's face depends on how long a victim saw the attacker, too. Research has shown that witnesses tend to overestimate the length of stressful events and think they saw a perpetrator for longer than they did, according to several studies by forensic memory expert and University of California at Irvine Professor Elizabeth F. Loftus. This can lead them to feel more sure about an identification than they should and, in turn, encourage inflated confidence in police, attorneys or juries. Race has been shown to have a huge impact on the ability to remember faces accurately. During the attempted robbery for which Houston was booked, the assailants were black and the victim was not. People generally have a hard time distinguishing faces of people of races other than their own, said psychologist Reisberg. This can wreak havoc for victims during eyewitness identifications. "If you've got a (lineup) situation in which the actual perpetrator is not present, the risk of a bad pick goes up by almost 60 percent when it's cross-race identification," he said. As his days in jail stretched into a second month, Houston said he thought there was a good chance he'd be convicted of a crime he never committed. "I thought I was going to get charged for the whole thing," he said. His father, Richard Houston Sr., visited often and reminded him not to respond to inmates who tried to pick fights. "My dad wouldn't let me get depressed." In jail, Houston learned to hate 26-hour lockdowns, the spoiled milk and bugs in his beans, and guards who treated him like a guilty man. Once, when his father was leaving after a visit, he cried for the first time since his parents' divorce in 2000. "It was all cool through the whole visit," Houston said. "Then he had to make it all movie scene. He put his hand on the glass. I thought, 'Why should I have to touch my dad through glass?' " Houston and his family could not afford his bail. Since his release, Houston said he's taken more time to look at the stars. One day, he sat in the rain for an hour just because he could. He's been playing with his new pit bull puppy and writing about what happened. He's also looking for work. He was supposed to start a job days after his arrest; the position wasn't open when he got out. Houston said the relief of his release outweighs any anger he felt at being locked up. His father is not so forgiving. "It was blatant that they tried to frame him," he said. "They tried to frame him and tried to push him through the court, to take a plea." Watching Houston sit in jail, said best friend Mota, undermined what little faith he had in the justice system. He watched Houston get arrested after Mota was forced, along with Mota's 15-year-old brother, to stand in a lineup outside his home. The same night, Mota saw his dog pepper-sprayed and a light on his house broken by police. The police, he said, decided Houston was the robber, then failed to pursue evidence that might have freed him. "How do you arrest somebody and make them your No. 1 suspect so fast? There has to be further investigation," he said. Several elements from Aug. 15 still don't add up. In early November, the victim said he told police the night of the attack he had seen his assailants at Stop N Save. This information was not in Steele's police report. Police said they did not learn this until early September, when the victim approached police at the Stanislaus County Courthouse and said he wanted to add to his statement. Houston had been in jail for three weeks. Had police known the assailants were at the market, they would have scrambled to watch the surveillance tape, Steele said Sunday. Even after the victim told police about seeing the robbers earlier, it took more than a month for someone to track down the store surveillance tape, despite efforts by Houston's defense attorney, Robert Schell, to see it sooner. It usually takes about two weeks to get this kind of evidence, said Baker, the deputy district attorney. After waiting for the tape for three or four weeks, Baker said, he learned that the police detective charged with getting the tape had been out of the office on training or vacation. Baker rushed to pick up the tape and watch it; Houston was released the next day. Putting together a puzzle Eyewitness identification is just one piece of evidence police gather when they try to connect a suspect to a crime, Gundlach said. They evaluate whether someone matches the suspect's description. They consider the time and location of the crime and whether a suspect was nearby. They look at someone's behavior to see whether it's suspicious. "The test comes back to what's reasonable to the officer," he said. "There was plenty of information that night to think that (Houston) could have been the right guy." But although Modesto police followed procedure, an innocent man spent nearly two months in jail. Recent studies on memory, lineup structure and identification techniques have urged more stringent guidelines for law enforcement. Several states have adopted such guidelines. California was not among them. For many agencies, however, there just isn't time to gain a deep understanding of how memory works. "Police are responsible for knowing 43 million different things," said psychologist Reisberg. "How to recognize different kinds of weapons, drive really fast if you're chasing somebody, understand search warrants and probable cause. We're asking them to do one hell of a difficult job." Cadets at the Ray Simon Regional Criminal Justice Training Center in Modesto receive 31⁄2 pages of reading on eyewitness identification procedures; most of what they learn happens after they graduate from the academy, said director Lt. Jim Gordon. He said the academy would consider assigning a research paper on memory and eyewitness identification to cadets. Some experts say it's not enough. With few exceptions, the legal system has not conducted research on eye- witness evidence, has never conducted an experiment on memory and has no scientific theory about how memory works, according to one of the leading experts on memory research, Gary L. Wells, a professor at Iowa State University. "Police receive inadequate or no training in carrying out reliable and valid eyewitness identification procedures," said psychologist Shomer. But for the wrongfully accused who wind up in Houston's shoes in Stanislaus County, there's a chance their innocence could be overlooked. In her experience, situations such as Houston's happen at least several times a year, said Martha J. Carlton-Magaña, a Modesto defense attorney who worked for the Stanislaus County public defender's office for two decades before retiring in April. It's impossible to know for sure how often this happens, because DNA evidence, which isn't available in most cases, is the primary tool for exonerations. Houston, she said, should consider himself lucky. Many defendants represented by public defenders never get to tell their side of the story; the office doesn't have the budget for an interviewer and attorneys barely get to look at their clients' files before court appearances, she said. People often sit in jail longer than they should, she added, because lawyers do not appear during arraignment, where they would have the chance to request a bail reduction or that their clients be released on their recognizance. "Our system is broken in this county because we don't have the checks and balances in place that we should," she said. Chief Deputy District Attorney John Goold said Houston's release shows the opposite. "As much as possible, we can't have people in jail who did not commit crimes. When it happens, we want to find out as soon as possible," he said. "In all honesty, you have to say the system as a whole worked, even though he had to spend some time in jail." Bee staff writer Emilie Raguso can be reached at eraguso@modbee.com or 5782235.