Iowa Farmer Today 07-14-07 Yield monitors, GPS aid on-farm trials

advertisement

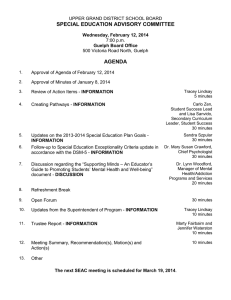

Iowa Farmer Today 07-14-07 Yield monitors, GPS aid on-farm trials By Tim Hoskins, Iowa Farmer Today MASONVILLE -- Like many farmers, Dennis Lindsay wants to be sure he makes the right decision when he changes a practice on his Buchanan County farm. To help him make any changes, he started using precision ag tools, such as yield monitors and GPS systems, to experiment in 1994-95. Looking at N rates for his corn was one of his first areas to experiment with. He wrote a prescription, including one that followed Iowa State University’s recommendation. After collecting the information, he contacted the late Fred Blackmer, Iowa State University agronomy professor. “That was a rude awakening,” says Lindsay. “We were lacking the skills to do it right.” Thought is the first thing needed to conduct an effective on-farm experiment, he notes. “To get a good answer, you need to think about the question,” says Tracy Blackmer, director of research for the Iowa Soybean Association (ISA) On-Farm Network research program and Fred’s son. The answer you are seeking affects how the trials should be planned and conducted. “It takes a lot of thought to set up a trial right,” Lindsay says. Laying out replications is one of the more important steps in planning on-farm trials. “Get replications, one can be an oddity,” he says. Blackmer says farmers want to keep consistent as many other factors — such as population, variety/hybrid, and time of applications — to test one variable at a time. Farmers should look at big things first, then work on refinements, he says. For example, in trials for the optimal fertilizer rate, Blackmer says a cut of 50 pounds per acre might help find the correct application. He says the optimal amount of fertilizer could be 100 lbs./acre. If a farmer compared 150 lbs. to 125 lbs./acre, there would not likely be much difference in yield because there was more than enough fertilizer in both cases. After conducting the trials, the results are collected. However, Lindsay cautions other farmers the results might not be what they predicted. For example, he did N research on a field he can see from his Northeast Iowa living room. Throughout the growing season, one strip was greener, and all the tests throughout the summer indicated it would outperform the other areas. However, when the combine rolled through the field, there was only one bushel difference between the two fertilizer rates. To collect the data, Lindsay says farmers need a properly calibrated yield monitor combined with a global-positioning system. Lindsay downloads the information daily from his yield monitor. He then makes maps and lays them on the desk. He says he then can see some changes, and those changes can be connected to management practices. An example would an area in a field that yielded higher than other areas might be close to where manure was spread. However, the lines on the yield map tend to be a little fuzzy, Lindsay warns. One of the reasons is the delay in the yield monitor. As information is being read by the yield monitor, it likely has happened 20-30 feet behind the combine. In addition, he says not everything in nature cuts off at a nice line. For example, he says one treatment might not show a direct result exactly where soil types change. Lindsay advises farmers to network with others who are conducting similar work. He meets with a group of farmers in his area to compare results. If his results match similar trials conducted by other farmers, Lindsay says that gives him some confidence in his results. “We very seldom look at one year’s data to make changes,” he says. Lindsay works with the ISA On-Farm Network. As part of that group, his data is collected and analyzed by the ISA. The data is also combined with similar data throughout the state. Lindsay says there is a benefit to having other people looking at the data. He concedes he is not a statistician. Therefore, he allows others to look over his data to see if any changes were caused by a management modification or other factors, such as elevation or rainfall and if any change was significant. After getting help from an outside source to look at the data, Blackmer says the next step is to change management practices if needed. “Why do a study if you are not going to follow the answer?” he asks. Blackmer suggests farmers conduct trials in areas where they are the comfortable with their management practice. Adding to his comfort level is one of the reasons Lindsay conducts on-farm trials. Trials sometimes confirm farmers are doing the correct practice. Other times, it might give them the confidence to make changes. “It helps us feel comfortable of what we are doing,” Lindsay says.