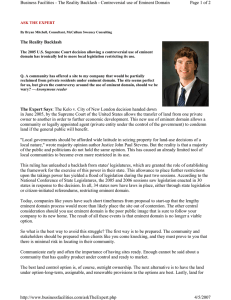

Des Moines Business Record 11-20-06 How to handle eminent domain disputes

advertisement

Des Moines Business Record 11-20-06 How to handle eminent domain disputes You are notified that your city government is interested in buying your property "at a reasonable price." The area is to be developed into a shopping and entertainment quarter. You and your neighbors live in a quiet, peaceful part of town, close to amenities. But you know that if a settlement is not reached between you and the city, the city might be able to take your property anyway through "eminent domain." The city argues that, although little of the area has actually been claimed by developers, this is the best area for development. Besides, it fits well with the city's Conceptual Development Plan. The way you see it is that because of a distant promise of increased tax revenues and growth, the city is destroying a wonderful neighborhood. The city council has no visible incentive to ensure that growth will actually materialize and little reliable expertise in knowing or understanding what really works. The city leaders are relying on engineering and economics staff people who might know very little more. You cannot help wondering if someone in the government has been offered private incentives to open the area to development. The mayor and council, on the other hand, want to make real progress during their watch. They see your neighborhood obstructing commercial expansion by sitting in the path of the growth the CDP promises. By opening this area rather than an undeveloped section, new street access and utility trunk lines will not be necessary. Moreover, a number of developers have expressed interest in the area. They can only see the good in the exercise of eminent domain if necessary, resulting in lower taxes for residents and new and exciting facilities for the community. Who is right? Both sides have valid points, but there are realities: 1. Governments have no immediate and direct incentives to ensure positive longterm growth. Hence we must trust in their dedication to the common good, yet be watchful for ulterior motives, 2. Few have the expertise and experience to predict what specific part of a city will be most attractive to future business, or fit best with future product and service delivery modes. Interference with natural market progression may result in negative consequences, 3. Many developers do not know when to stop. An example is Houston in the 1980s. Once they are done with one project, they will pour themselves into the next. After all, developing is what they do, 4. Business development increases the tax base and often improves employment. Business taxes are more efficient than residential. For every tax dollar the city receives, it pays out $1.22 in services for residential properties but only 30 cents for commercial. 5.With growth come problems: more traffic, more demand for services -- water, police, fire protection, snow removal, etc. What is the solution? We are firm believers in markets. Unimpeded, they can work for the public good. But is it good to handcuff local governments with laws that can suppress progress? The solution is in the community itself. We all must be mindful of what is happening to our city and our citizens. With open-meeting laws, access to all kinds of information and the ability to meet with members of government at every level, there is little excuse to let city officials ramrod their plans for the future through to fruition. No project can be completed without community support -- either directly or by lack of opposition. When someone else's neighborhood is threatened by eminent domain, you must ask yourself two questions: 1.Is this right for our community? 2.Will they be coming for my house next? Rick Carter, professor of finance, and Larry Curtis, adjunct assistant professor of accounting, teach in the College of Business at Iowa State University.