Des Moines Register 03-28-06 DNA digs into family tree

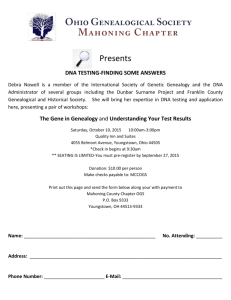

advertisement

Des Moines Register 03-28-06 DNA digs into family tree An Urbandale man goes high-tech to trace his ancestry and uncover previously unknown relatives. By MARY CHALLENDER REGISTER STAFF WRITER Larry Slavens has spent years researching his family history the traditional way: interviewing elderly relatives in Hendricks County, Ind., writing down names and dates from crumbling tombstones, searching through yellowed documents, scanning miles of microfilm. When it comes to filling in the missing pieces, though, the 48-year-old Urbandale computer analyst is counting on a high-technology solution. Slavens is the administrator and charter member of the Slaven DNA project, an ongoing study that relies on genetic markers to determine if families with surnames similar to his are connected — and if so, how far back in history. Genetically, humans — regardless of where they come from or what their ancestry is — are far more alike than different. Scientists mapping the human genome in 2000 found it consisted of about 3 billion pairs of DNA chemicals or "letters," and that those letters were 99.9 percent similar from one person to the next. It's within that 0.1 percent difference that the science of genetic genealogy was born. Just like notations in an old Bible or census records, family history is recorded in our genes. A father's Y chromosome DNA is passed down virtually unchanged to his sons while mothers pass down their mitochondrial DNA to their sons and daughters. Over generations, certain patterns of enzymes — or genetic markers — develop and are repeated within the DNA of families. So by comparing two or more sets of genetic markers, it is possible to determine if the individuals are related. In the past six years, genetic genealogy has become a booming business, doubling nearly every year, according to Max Rothschild, a distinguished professor of agriculture at Iowa State University and a member of Family Tree DNA's scientific advisory board. Tens of thousands of Americans have swabbed their cheeks and paid upward of $100 in the hope of finding unknown relatives and filling in the gaps in their family history. "Genomics is the wave of the future and genetic genealogy uses that technology to bind us with our past," he said. Bio-geographical projects have also emerged, such as the research at Trinity College in Dublin linking descendants of Niall of the Nine Hostages — who may have kidnapped St. Patrick to Ireland — to an area in northwest Ireland and the African-American Roots project at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. Perhaps the most ambitious genetic genealogy undertaking of all is the five-year Genographic Project spearheaded by National Geographic, which hopes to collect 100,000 DNA samples from indigenous populations worldwide in order to determine the origin of man. Slavens would be content if his project helps pinpoint the origin of his family. How it all began Born and raised in Earlham, Slavens said his interest in genealogy was reawakened about five years ago after taking a Civil War correspondence course. He learned one of his ancestors on his mother's side had served in the war, so he began doing more research on the man. This led Slavens to Hendricks County, Ind., where both his parents had ancestors, 100 years before they met in Iowa, he said. Over the past few years, he's made several trips to Hendricks County, where he's walked through the abandoned Slavens family cemetery, found old marriage records and exchanged family stories with third cousins. One of the biggest frustrations of this kind of paper-based research, Slavens said, is that once you go back earlier than the late 19th century, official documents are scarce. Slavens started his DNA project three years ago. He paid about $170 to have his genetic profile charted — less than a visit to Hendricks County probably cost him, he said. Because he was the first in the family to have his DNA mapped, at first the test didn't tell him much. "You get a bunch of numbers," he said. "It's when you compare your bunch of numbers to other bunches of numbers that it gets interesting." Slavens said his family DNA project now has about two dozen members and a few mysteries have been solved. He said the Slavenses make up a large family with thousands of American descendants. Within the family is a North Carolina line and a Virginia line, he said. For years, family historians speculated that the two lines had been started by brothers. "Once we started testing, we could immediately tell, nope, there was no connection between the two families, at least not for hundreds of years," Slavens said. Slavens is hoping the DNA research will help him learn about the family patriarch, a man of Irish ancestry he thinks comes from County Tyrone because that's where all the family stories are from. "Perhaps through DNA testing, we'll be able to hook up with family that are still in Ireland or have gone to Scotland but still knows, yes, we were from this town," he said. Caveats lurking There's a chance DNA testing will expose some dark family secret, Slavens acknowledged. Although that hasn't happened in his project, he's heard some sad stories. One was about an elderly man who was devastated to find he didn't match immediate family members. Eventually, the man learned had been the child of other relatives and taken in. "He came away with more compassion for his family, but it was definitely a shock," Slavens said. Genetic genealogy has its limitations. Sometimes people are tested only to find out they don't match anybody — at least initially. "Even if someone has a common name, they may be from an unusual branch of a family and not have a match with anyone for some time," Slavens said. The other limitation is that most DNA projects follow the male Y-DNA line, so only male members of the family can be tested. For women or those interested in tracing their female line, there are mitochondrial DNA projects. One advantage of genetic genealogy is that it opens a window for people who can't trace their genealogy the traditional way, often because a parent or grandparent was adopted. Slavens said several public databases are available for people to post their DNA markers. Chances are, eventually they'll find a match. That's what happened with one of Slavens' project members, who knew from the start that one of his great-grandfathers wasn't really a Slavens. "When he was tested, his markers were way out there," Slavens said. "He put his numbers up on a database strictly on the hope his markers would be associated with someone in the county his ancestor was born in. Nine months ago, he had a hit. Now he's investigating if that family had a male of approximately the right age." Rothschild hopes genetic genealogy will help people understand the myriad ways our separate family trees are intertwined. As we search the world for others who share our genetic pattern, what we'll find, he says, is "there has been an enormous mixing of the human experience." "Sooner or later we can probably easily say we were all related at one time," Rothschild said.