ISU researchers study winter habits of mice for clues Agri News, MN

advertisement

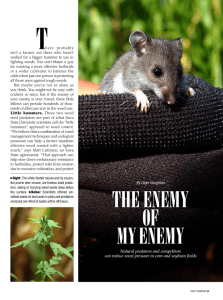

Agri News, MN 02/14/06 ISU researchers study winter habits of mice for clues AMES, Iowa -- Researchers at Iowa State University hope what they're learning about the winter habits of mice may lead to better weed control with less reliance on herbicides. A new project that builds on work funded by the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture has received a three-year $499,500 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service (CSREES). It was one of 15 grants awarded to support a national research initiative on the biology of weedy and invasive species that cause environmental damage and losses adding up to more than $100 billion per year. "For the last four years, we've been keeping a detailed account of what goes into and what comes out of the bank of weed seeds in the soil," said ISU agronomy professor Matt Liebman, who leads the project. "We measure the number of seeds in the soil at the start of every growing season, count the number of emerged seedlings, and determine the number of new weed seeds produced and shed back onto the soil. Using simple input-output accounting methods, we figure that 70 to 90 percent of the weed seeds that should be in the soil aren't there." So what happened to those "missing" weed seeds? "We think most of the missing seeds have been consumed by insects and rodents that live in crop fields," Liebman said. "This project attempts to get a better picture of the effects of various cropping systems on deer mice and other species in the seed-eating community. We're particularly interested in how these animals can contribute to better control of weeds." The prairie deer mouse, one of North America's most abundant vertebrates, lives in the middle of fields. Its cousin, the white-footed mouse, lives near field borders. The ISU team has found that both species are major consumers of weed seeds during the summer, but little research has been done on the winter habits of these mammals. The research began in 2002 on 36 test plots at the ISU Marsden Farm in eastern Boone County, and in larger fields on other ISU farms. The Marsden farm plots compare the effects of three different crop management systems on velvetleaf and giant foxtail: --a conventional corn-soybean rotation, --a three-year rotation for producers who use or market small grains (cornsoybean-triticale underseeded with red clover for soil improvement), and --a four-year system for producers with livestock eating forage (corn-soybeantriticale underseeded with alfalfa-alfalfa for hay). During the past two seasons, the researchers measured no tonly weed seed longevity in the soil, weed seedling emergence and survival, and weed seed production, but also weed seed loss to insect and animal predators. Losses to predators were determined by lightly gluing weed seeds onto squares of sandpaper and placing the seed cards throughout fields for 48-hour periods between April and November. Averaged over 27 measurement periods in two years, about one-third of the velvetleaf seeds and half of the giant foxtail seeds were lost to predators within two days. In 2003, the loss of velvetleaf seeds to predators was greater in the four-year rotation than in the two-year rotation. Overall, seed predation patterns in the different crops were complementary. For example, in triticale the largest number of weed seeds was consumed in the spring, whereas weed seed consumption in corn and soybean was greatest in late summer and early fall. "Simple rotations require more herbicides than four-year rotations because you do not have diverse weed control practices in place," Liebman said. "We're really interested in the effects of different crop habitats and tillage practices on seed predation so we can take advantage of it and other ecological processes." The new project uses special cages to regulate access to seeds between November and April so the researchers can measure rates of weed seed predation that occur after the harvest of one crop and before planting another. The researchers also will examine DNA in the feces of mice live-trapped during the winter to determine what and where the animal has been eating. The project represents a unique collaboration between two weed ecologists, Liebman and Paula Westerman, both in the Department of Agronomy, and an animal ecologist, Brent Danielson from the ISU Department of Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology. During the past two years, Liebman, Westernman and Danielson have offered their research results as part of a field school on weed ecology and management for farmers, funded by the Leopold Center. They also have been comparing the related costs and income from the three cropping systems.