IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DIVISION

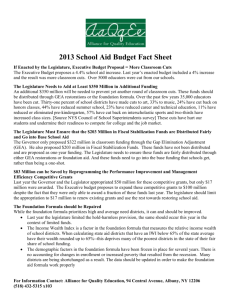

advertisement