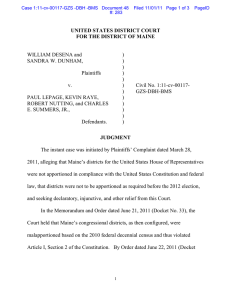

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DIVISION

advertisement