UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN

advertisement

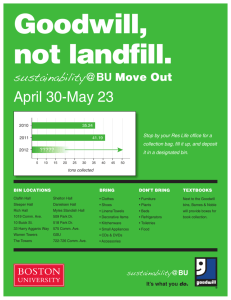

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN ALVIN BALDUS, CINDY BARBERA, CARLENE BECHEN, RONALD BIENDSEIL, RON BOONE, VERA BOONE, ELVIRA BUMPUS, EVANJELINA CLEEREMAN, SHEILA COCHRAN, LESLIE W. DAVIS III, BRETT ECKSTEIN, MAXINE HOUGH, CLARENCE JOHNSON, RICHARD KRESBACH, RICHARD LANGE, GLADYS MANZANET, ROCHELLE MOORE, AMY RISSEEUW, JUDY ROBSON, GLORIA ROGERS, JEANNE SANCHEZBELL, CECELIA SCHLIEPP, TRAVIS THYSSEN, Civil Action File No. 11-CV-562 Plaintiffs, TAMMY BALDWIN, GWENDOLYNNE MOORE and RONALD KIND, Three-judge panel 28 U.S.C. § 2284 Intervenor-Plaintiffs, v. Members of the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, each only in his official capacity: MICHAEL BRENNAN, DAVID DEININGER, GERALD NICHOL, THOMAS CANE, THOMAS BARLAND, and TIMOTHY VOCKE, and KEVIN KENNEDY, Director and General Counsel for the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, Defendants, F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., THOMAS E. PETRI, PAUL D. RYAN, JR., REID J. RIBBLE, and SEAN P. DUFFY, Intervenor-Defendants, (caption continued on next page) JOINT BRIEF OF BALDUS AND VOCES DE LA FRONTERA PLAINTIFFS IN SUPPORT OF PROPOSED REMEDY FOR VOTING RIGHTS ACT VIOLATION Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 1 of 13 Document 224 VOCES DE LA FRONTERA, INC., RAMIRO VARA, OLGA VARA, JOSE PEREZ, and ERICA RAMIREZ, Plaintiffs, v. Case No. 11-CV-1011 JPS-DPW-RMD Members of the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, each only in his official capacity: MICHAEL BRENNAN, DAVID DEININGER, GERALD NICHOL, THOMAS CANE, THOMAS BARLAND, and TIMOTHY VOCKE, and KEVIN KENNEDY, Director and General Counsel for the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, Defendants. The Court’s March 22, 2012 Memorandum Opinion and Order was unequivocal: plaintiffs prevailed “because Act 43 fails to create a majority-minority district for Milwaukee’s Latino community.” Mem. Op. (Dkt. 210) at 33. The evidence presented at trial “supports the need for a functioning majority-minority district . . . , not just one or two influence districts.” Id. at 31-32 (emphasis added). Once the legislature declined to revisit redistricting, the Court established the (literal) boundaries of party submissions on the remedy: they “should confine their suggested changes to fall within the outer district boundaries of Assembly Districts 8 and 9 as established by Act 43.” March 27, 2012 Order (Dkt. 218) at 3-4. The Baldus plaintiffs and the Voces de la Frontera plaintiffs have complied with that mandate, proposing a cure for the fundamental flaw in Act 43. With this memorandum, and in the absence of an agreement with the Department of Justice (as reported yesterday to the Court), the Baldus and Voces plaintiffs (collectively “plaintiffs”) jointly submit a proposal for 1 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 2 of 13 Document 224 reconfiguring the two assembly districts—strictly within the outer boundaries created by Act 43. The proposal has these attributes: • It creates one district with a Hispanic-American citizen voting age population (“HCVAP”) of 55.22 percent, pursuant to the Voting Rights Act and this Court’s decision and judgment; • It reflects, unlike the process that led to Act 43, a consultative process in the wake of the Court’s decision with a broad, bipartisan collection of individuals and groups in the Latino community directly affected by these choices; • It maintains a minimal and acceptable deviation from population equality, -0.43 percent in District 8 and -0.28 percent in District 9; and • It is compact and retains 75.84 percent of the core population in District 8 (and 69.19 percent in District 9). Plaintiffs submit, for the Court’s consideration, a map of their proposed district boundaries, the development and demographics of which are explained by their expert, Dr. Ken Mayer. See Declaration of Dr. Kenneth R. Mayer (“Mayer Decl.”), ¶ 4, Ex. A. Plaintiffs’ proposed map also appears at page 11 of this brief. This Court has held that Act 43 violates federal law, enjoining its implementation. In the absence of a new redistricting statute, or the enactment of a substitute statute that cures the specific violations of federal law, “the task to make the changes required for a lawful redistricting plan now falls” to the Court. Order (Dkt. 218) at 3. It necessarily falls to the Court as well to adopt legislative boundaries for the entire state, not just part of the City of Milwaukee, to fill the complete void left by the invalidation of Act 43. While the Court is not the legislature and cannot amend a statute, it can and should—as it has done for the last three decades—promulgate by judicial order boundaries for the entire state. See, e.g., Wisconsin State AFL-CIO v. Elections Bd., 543 F. Supp. 630, 631 (E.D. Wis. 1982). Without that, the boundaries that remain are those adopted judicially in 2002, which—until judicially replaced—remain constitutional and will be the boundaries for all elections. See Mem. 2 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 3 of 13 Document 224 Op. at 33 (“[T]here is nothing unconstitutional at all about the 2002 districts for the period of time between the adoption of the map based on the 2000 census and the adoption of the map based on the 2010 census.”). DISCUSSION I. PLAINTIFFS’ PROPOSAL ENSURES THAT LATINO VOTERS CAN ELECT A CANDIDATE OF THEIR CHOICE BY SECURING AN HCVAP OF 55.22 PERCENT IN ASSEMBLY DISTRICT 8. In concluding that Act 43’s configuration of Assembly Districts 8 and 9 violated the Voting Rights Act, this Court asked “whether the redistricting plan in Act 43 provides Latino voters with an opportunity to elect a candidate of choice.” Mem. Op. at 26. Simply put, Act 43 failed that test. The legislature’s approach ostensibly was to create two influence districts by maximizing District 9’s Latino population but sacrificing an effective Latino voting majority in District 8. Rejecting that approach, the panel found it “apparent that Latino voters have a distinctly better prospect of electing a candidate of choice with one majority-minority district than two influence districts.” Id. at 27-28. Because it denied Latino voters that opportunity, Act 43 violated section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The requirement that Latinos comprise an effective majority of District 8 voters was but one part of the Court’s holding, a holding that—critically—also spelled out how that majority is to be measured. The relevant metric, the Court explicitly held, is “citizen voting age population, at least for an ethnic group with as high a proportion of lawful non-citizen residents as the Latinos.” Mem. Op. at 24. The Department of Justice and its own expert “appeared [to] concede[]” this point as trial unfolded. Id. It is a point difficult to escape. As this panel recognized, the Supreme Court requires courts “to take real voting majorities into consideration; just as we do not include children in those numbers, we cannot include non-citizens who do not enjoy the franchise.” Mem. Op. at 31 3 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 4 of 13 Document 224 (citing League of United Latin Am. Citizens (“LULAC”) v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399, 429 (2006)). Citizen voting age population is the standard measure of Latino voting power. Indeed, on remand from the Supreme Court in Perry v. Perez, 555 U.S. __, 132 S. Ct. 934 (2012), a panel in the Western District of Texas applied HCVAP to implement districts for the Texas legislature. Perez et al. v. Texas et al., No. 11-CV-360, Op. (Dkt. 690) at 9-10 (W.D. Tex. Mar. 19, 2012). The importance of distinguishing between the Latino voting age percentage and the Latino citizen voting age percentage was emphasized earlier in Gonzalez v. City of Aurora, 535 F.3d 594, 596-97 (7th Cir. 2008), where the Court noted that even a “rule of thumb” of 65 percent Latino voting age population may not be enough. See also Barnett v. City of Chicago, 141 F.3d 699, 703 (7th Cir. 1998) (“[B]ecause of both age and the percentage of noncitizens, Latinos must be 65 to 70 percent of the total population in order to be confident of electing a Latino.”). The Department of Justice’s reservation of rights in this regard, see Joint Report (Dkt. 220) at 3 n.1 (“Defendants do not concede that CVAP is the ‘relevant measure’ for evaluating a district under the Voting Rights Act.”), only highlights the stark difference in approach. So do the proposals it presented during the meet-and-confer. The discussion of its proposal, in whatever shape it ultimately takes, will await Thursday’s response. To calculate the HCVAP figure for their proposed districts, plaintiffs apply a 42 percent Hispanic non-citizen factor for the City of Milwaukee. As plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. Ken Mayer, testified at trial, 42 percent is “the non-citizenship rate among the Latino voting age population in Milwaukee” according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (“ACS”) from 2006 to 2010. Trial Tr. vol. IV (Dkt. 195) at 188:24-185:1; see also Mayer Decl. ¶ 7. Dr. Mayer considers this figure a more precise estimate than the 35.75 percent statewide Latino non- 4 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 5 of 13 Document 224 citizen rate cited in his initial report. Trial Tr. vol. IV at 188:7-17. That lower rate was based solely on the 2008 annual ACS. Id. The “five-year data” used to calculate the 42 percent rate “is universally considered to produce better estimates” than the ACS’s annual surveys “because you have five times as much data.” Trial Tr. vol. IV at 188:16-189:1. In addition, the 42 percent factor is based on “the geographic aggregation of Milwaukee city,” whereas 35.75 percent was statewide. Id. at 188:20-22. Using the non-citizen rate of 42 percent, Dr. Mayer testified at trial that the HCVAP in Act 43’s Assembly District 8 was only 47.07 percent—a figure that this Court relied on in its decision. Mem. Op. at 26-27. It is only appropriate—indeed, more so1—to apply the same methodology to calculate the HCVAP for plaintiffs’ District 8, as Dr. Mayer has done in plaintiffs’ proposal. Plaintiffs’ proposed District 8 has an HCVAP of 55.22 percent. This is necessarily larger than a bare majority because—as Dr. Mayer testified at trial—voter turnout among Latinos “is exceptionally low.” Trial Tr. vol. IV at 194:13-16. Even accounting for citizenship status, a bare majority is simply not enough to satisfy section 2’s requirement that Latino voters be able “to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” 42 U.S.C. § 1973(b). The concept of an effective voting majority is not new under the Voting Rights Act. See, e.g., McNeil v. Springfield Park Dist., 851 F.2d 937, 945 (7th Cir. 1988); United States v. City of Euclid, 580 F. Supp. 2d 584, 594 (N.D. Ohio 2008). It is, after all, the Voting Rights Act, not a resident rights act. An HCVAP of at least 55 percent provides a sufficient margin to account for 1 “A court-ordered plan . . . must be held to higher standards than a State’s own plan.” Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 26 (1975). 5 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 6 of 13 Document 224 low turnout and protect the voting rights of Latino citizens without “packing” too many into a single district or, as Act 43 did, dispersing them and diluting their concerted voice. II. PLAINTIFFS’ PROPOSAL IS THE PRODUCT OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND ENJOYS COMMUNITY SUPPORT, AND IT MEETS TRADITIONAL REDISTRICTING CRITERIA. Of course, the crafting of district boundaries cannot be reduced to a pure mathematical exercise. A reconfigured District 8 that reached a HCVAP of 55 percent but split apart Cesar Chavez Drive—“the heart of the Hispanic community,” Trial Tr. vol. IV (Dkt. 195) at 113:11-22 (testimony of John Bartkowski)—would ignore the community’s natural boundaries. As community leaders emphasized from the outset, a majority-minority Latino district cannot divide the community’s commercial hub. To determine the other features to prioritize in a court-ordered district, Voces counsel have conferred extensively with members of Milwaukee’s Latino community in the brief window allowed by the remedial phase of this lawsuit. See Declaration of Peter Earle (“Earle Decl.”), ¶¶ 3-17. Presented with multiple configurations that each maintained an appropriate HCVAP, the Latino community has coalesced around a District 8 map that captures—on its east side—the Walker’s Point neighborhood and the business development corridor along South First and South Second Streets. They also support a map that maximizes an effective voting majority of citizen voting age Latinos while satisfying traditional redistricting principles such as geographic compactness, core retention, and minimal population deviation. 6 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 7 of 13 Document 224 This proposal, which plaintiffs now present to the Court, has been endorsed by a bipartisan coalition of local Latino leaders.2 Milwaukee’s Latino community is diverse, and plaintiffs do not purport to speak for every Latino citizen. Nor would it be possible to do so.3 However, even the Department of Justice’s own expert, Ronald Keith Gaddie, expressed the importance of “having community input in the process.” Trial Tr. vol. VIII (Dkt. 203) at 559:1-2. Plaintiffs have done precisely that, speaking to a broad cross-section of the community and producing a consensus around a reasonable proposal. The legislature, by contrast, last year consulted with the community on only a narrow and political basis—winning the endorsement of Jesus Rodriguez of Hispanics for Leadership and Hispanics for School Choice, and “courting the[] approval” of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund in order to “take the largest legal fund for the Latino community off the table in any later court battle.” Mem. Op. at 7. The legislature failed to heed Dr. Gaddie’s advice last summer. And the legislature has similarly declined this Court’s invitation to remedy the infirmities of Act 43. Plaintiffs, to fill that void, have taken an the approach that the legislature should have followed from the outset. 2 They include Jose G. Perez, a real estate developer and candidate for the 12th Aldermanic District seat on the Milwaukee Common council; Ernesto Villareal, the owner of Supermercado El Rey, “Milwaukee’s only authentic Hispanic grocery stores”; John Bartkowski, the executive director of the Sixteenth Street Community Health Center and a witness at trial; Darryl Morin, the former president of the Wisconsin League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and chair of the Latino Redistricting Committee; Enrique E. Figueroa, the director of the Roberto Hernandez Center at UW-Milwaukee; Juan Carlos Ruiz, the coordinator of the Milwaukee Latino Redistricting Committee; Christine Neumann-Ortiz, the executive director of plaintiff Voces de la Frontera, Inc., and a witness at trial; Maria Monreal-Cameron, the president of the Hispanic chamber of Commerce of Wisconsin; Dr. Luis “Tony” Baez, the executive director of The Spanish Center; Ernesto Chacon, the former deputy director for Governor Doyle’s Milwaukee office; Steve Fendt, the executive director of the Southside Organizing Committee; Victor Huyke, publisher of the Latino newspaper, El Conquistador; Jesus Salas, a former regent for the University of Wisconsin system and civil rights leader in the Latino community; and Jocasta Zamarripa, the incumbent representative for Assembly District 8 in the legislature. See Earle Decl. ¶¶ 3-17. 3 There are some Latinos who advocated support for Act 43 and against configuring District 8 in a way that created an effective majority of voting age citizens who are Latino. 7 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 8 of 13 Document 224 The boundaries of plaintiffs’ proposed Assembly Districts 8 and 9 also meet traditional redistricting criteria and Wisconsin’s constitutional standards. The districts are compact with regular boundaries. Assembly District 8 is regularly shaped and follows important geographic features, using railroad lines, rivers, parks, and major streets as boundaries to the extent practicable. Mayer Decl. ¶ 6. The deviation of District 8 from the ideal population is -0.43 percent, and District 9 is -0.28 percent, both well within acceptable limits. Id. ¶¶ 6, 14. The proposal significantly increases District 8’s core population retention, retaining 75.8 percent of the population compared to 55.3 percent in the Act 43 configuration. Id. ¶ 11. III. STRICT ADHERENCE TO THE OUTER BOUNDARIES OF ASSEMBLY DISTRICTS 8 AND 9 IS NOT NECESSARY. Plaintiffs endorse the proposal submitted by the City of Milwaukee with its amicus motion, although it is not yet reflected in the plan plaintiffs submit today. The boundaries established by Act 43, the city notes, also create city wards consisting of a few blocks—in one instance, just one block. This is a direct result of two concerns expressly raised by the plaintiffs throughout this case: the “anomalies” created by the inability or unwillingness of the legislature to conform census blocks to established municipal boundaries, and the legislature’s complementary and unprecedented decision to impose its will on the municipal redistricting process through Act 39. See Mem. Op. (Dkt. 210) at 8 (“[U]pending more than a century of practice in Wisconsin, Act 39 required the municipalities to adjust their ward lines to the new state legislative districts.”). These problems arise directly from the legislature’s decision to ignore the command of the state constitution. See Wis. Const. art. IV, § 4 (requiring that legislative districts “be bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines . . . .”). The result, as this Court observed, was a top down, not a bottom up, process. See Mem. Op. at 5. 8 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 9 of 13 Document 224 If the Court accepts the Department of Justice’s perspective, it would not be able to make the common sense changes proposed by the City of Milwaukee—or any other improvements— finding itself bound by a strict reading of Perry v. Perez, 132 S. Ct. 934 (2012). But the U.S. Supreme Court was not so inflexible, and its decision in Perry is no straitjacket. The command that judicially created plans reflect “legislative policies” should not be read to require the adoption of every legislative choice in every legislative district. Indeed, the language in Perry, quoted by this Court, see Order (Dkt. 218) at 3-4, rests on the language in Abrams v. Johnson, 521 U.S. 74, 79 (1997), which in turn relied on Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37 (1982) (per curiam). In Abrams, ironically perhaps, the Supreme Court’s majority affirmed a district court decision that declined to adopt the explicit decision of Georgia’s legislature to create two African-American majority districts. See Abrams, 521 U.S. at 103 (Breyer, J., dissenting). The judicial plan established one. Indeed, in Perry, the legislatively enacted plan was not implemented because the state had not complied with section 5 of the Voting Rights Act—not because the plan itself was found invalid. In promulgating its own plan, as an interim measure pending the resolution of the section 5 dispute, the Texas panel drew interim congressional and legislative boundaries based on the legislative plan, ensuring the boundaries’ compliance with the Voting Rights Act. Here, of course, the legislative plan has been found invalid on its merits, not on section 5 compliance. Wisconsin is not a section 5 state. On remand, if not initially, the Texas panel now has applied both the command of Perry and that of Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. at 26, which establishes the rule that judicially adopted plans must meet higher standards than legislatively adopted plans. Those mandates permit both the correction of the two assembly district boundaries to meet the City of Milwaukee’s concerns 9 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 10 of 13 Document 224 and the implementation—if a party so moved—of corrective measures for other “infirmities” in what, until the Court invalidated the legislation, had been Act 43. This Court has expressed its discomfort with more than just the Voting Rights Act infirmities in Act 43. After a flawed process, the result was far from ideal. At the moment, the Court has asked for a remedy only for the Voting Rights Act violations, remedies circumscribed by the boundaries of two assembly districts as Act 43 established them. That may or may not be the conclusion of the remedial process here. The Department of Justice has suggested it might appeal. Motions for reconsideration can be filed until April 19 under Rule 59, Fed. R. Civ. P. In adopting a remedy for the two assembly districts, the Court should not foreclose looking beyond their boundaries should that become necessary or unavoidable. CONCLUSION For the reasons stated above, plaintiffs respectfully request that the Court adopt their proposed configurations for Assembly Districts 8 and 9 as part of its redistricting plan for the Wisconsin state legislature. 10 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 11 of 13 Document 224 Rd W W Clayton Crest Ave ve rA W Upham Ave St N Harb o r Dr NW ater S Austin St S Greeley St E Do E Montana St E Dewey Pl W Tripoli Ave S Aldrich St Par kR t d E Oklahoma Ave E Euclid Ave E Ohio Ave S Whitnall Ave S 1st Pl S 1st St S Chase Ave S Burrell St W Saveland Ave ver S E Holt Ave E Wilbur Ave E Howard Ave W Norwich St E Norwich St E Waterford Ave W Martin Ln W Allerton Ave W Armour Ave S Pine Ave S 5th St S 5th Pl W Armour Ave Ave S 3rd St S 5th Pl y ve ale A S Howell Ave State Hwy 38 S Burrell St W Edgerton Ave W Abbott Ave osed S 7th St S 6th St W W Halsey Ave ste Fo W Holt W Waterford Ave S 10th St W Cudahy Ave E Bay St W Oklahoma Pl Ave W Van Norman Ave S 14th St W Barnard Ave r hitake WW 41 £ ¤ Rl w Pa ci fic W Sonata Dr E Stewart St S 1st St North-South Fwy S 5th Pl S 5th St WR E Bolivar Ave E Armour Ave E Layton Ave W Vogel Ave W Edgerton Ave E Jose ph M H W Abbott Ave utste S 3rd St Canterbury S 21st St S 27th St W Vogel Ave Airport Fwy State Hwy 241 S 26th St W Holmes Ave S 8th St S 7th St S 6th St S 15th Pl S 15th Pl S 15th St S 15th St S 14th St S 14th St S 13th St S 12th St S 11th St S 10th St S 9th Pl S 9th St S 8th St S 7th St S 16th St W Crawford Ave Ca na di an S 20th Pl S 22nd St W Wilbur Ave 36 Service Rd W Barnard Ave S 6th St S 5th St S 4th St S 3rd St S 2nd St S 9th St S 18th St S 20th St S 28th St S 26th St S 25th St S 24th St S 23rd St 9 W Morgan Ave y Hw S 36th St S 35th St St at e St S 38th W Layton Ave S 37th St S 36th St N 8th St N James Lovell St N 6th St N 5th St N 4th St N 3rd St N 16th St S 15th St S 15th St S 14th St S 14th St S 13th St S 12th St S 11th St S 11th St S 10th St S 28th St S Layton Blvd S 26th St S 25th St S 24th St S 24th St S2 S 23rd St 3rd St S 22nd St S 21st St S 32nd St S 31st St S 30th St S 29th St S 34th St S 33rd St S 32nd St S Point Ter N 14th St N 20th St N 19th St State Hwy 57 N 32nd St N 31st St N 30th St S 34th St S 34th St S 33rd St S 40th St S 39th St S 38th St S 38th St S 37th St S 40th St St S 40th St S 19th St S 37th St S 36th St S 38th St S 43rd St Miller Park Way S 43rd St S Cherokee Way W Holt Ave W Bolivar Ave W Bottsford Ave I- 894 W Mitchell St W Maple St E Maple St W Ohio Ave W Plainfield Ave W Coldspring Rd n y Dr W Colo 42 nd S S 41st St N 26th St N 25th St N 37th St N 35th St N 34th St N 39th St S 41st St S 40th St S 38th St S 45th St S 44th St S 44th St S 44th St W Euclid Ave S T 32 W Hayes Ave E Greenfield Ave 32 y d W Lapham Blvd W Arthur Ave W Harrison Ave W Oklahoma Ave W Warnimont Ave W Howard Ave R is W Orchard St St Hw 36 S T 8 38 S T I- 43 I- 94 241 S 25th St S 45th St S 43rd St W Madison St W Dakota St S T57,283 Pop.: W Euclid Ave La Dev.: -0.28% ke W Po fie HVAP: 47.52% eS ld Dr t HCVAP: 34.78% Core Retn.: 69.19% W St W Virginia St 57,196 W BrucePop.: St W Montana St W Kinnickinnic River Pkwy W Manitoba St W Oregon St Er ie e at St W Lincoln Ave W Cleveland Ave W Montana St E St Ave W Canal St er at W W Grant St m I- 794 East-West Fwy S S 44th St W om Lo W W Rogers St ve eA E Kilbourn Ave E Wells St E Mason St Dev.: -0.43% HVAP: 67.68% E National Ave W Walker St W Mineral St HCVAP: 55.22% E Washington St W Elgin Ln Core Retn.: 75.84% W Becher St Ho ill St S 6th St S 44th St N 44th St y Pkw er Mill H te Sta abs t W t re s Fo ry H W Mount Vernon Ave W Burnham St W Grant St W To Bo W wS A rr t ow St W Mitchell St W Lapham St 24 S T 4 W Scott St W Greenfield Ave US Hwy 18 W Pierce St State Hwy 59 W National Ave WP 2 wy Joint Plaintiffs Proposed Remedy W Wells St W Wisconsin Ave W Michigan St W Clybourn St W St Paul Ave 94 I W Park Hill Ave US Hwy 41 W State St W Kilbourn Ave W Wells St N Jackson Pl St ch N 41st St on ar N Cass St M N 41st W wy 119 State H Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 12 of 13 Document 224 iner D r Dated: April 3, 2012. LAW OFFICE OF PETER EARLE LLC By: s/ Peter G. Earle Peter G. Earle State Bar No. 1012176 Jacqueline Boynton State Bar No. 1014570 839 North Jefferson Street, Suite 300 Milwaukee, WI 53202 414-276-1076 peter@earle-law.com Jackie@jboynton.com Attorneys for Consolidated Plaintiffs Dated: April 3, 2012. GODFREY & KAHN, S.C. By: s/ Douglas M. Poland Douglas M. Poland State Bar No. 1055189 Dustin B. Brown State Bar No. 1086277 One East Main Street, Suite 500 P.O. Box 2719 Madison, WI 53701-2719 608-257-3911 dpoland@gklaw.com dbrown@gklaw.com Attorneys for Plaintiffs 7711837_5 12 Case 2:11-cv-00562-JPS-DPW-RMD Filed 04/03/12 Page 13 of 13 Document 224