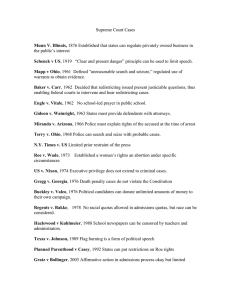

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY COVINGTON DIVISION

advertisement