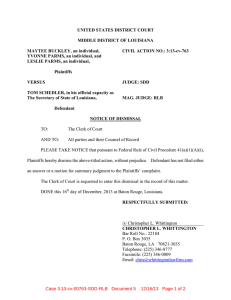

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA KENNETH HALL,

advertisement