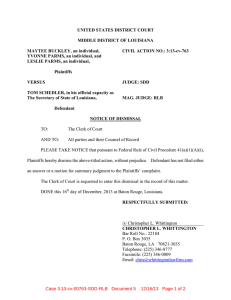

Case 3:12-cv-00657-BAJ-RLB Document 548 12/10/14 ...

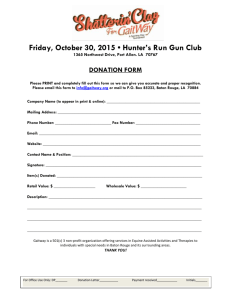

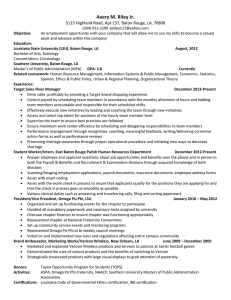

advertisement