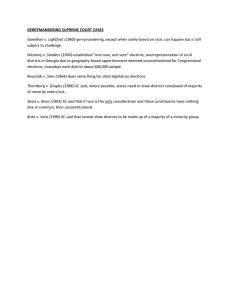

Supreme Court of the United States

advertisement