Document 10728650

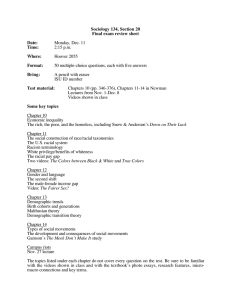

advertisement