IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

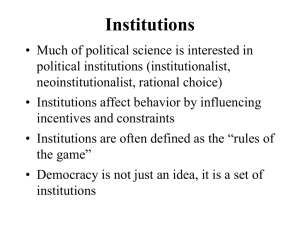

advertisement