( OPENING UP OF THE BAD AROLSEN HOLOCAUST ARCHIVES IN GERMANY HEARING

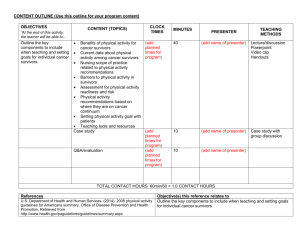

advertisement