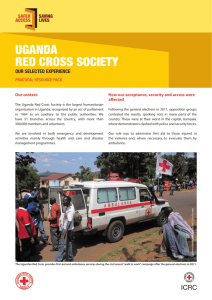

( THE ENDANGERED CHILDREN OF NORTHERN UGANDA HEARING

advertisement