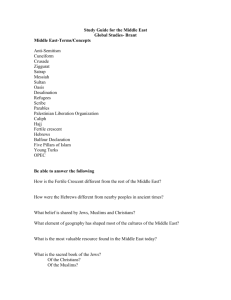

( IS THERE A CLASH OF CIVILIZATIONS? CENTRAL ASIA POLICY

advertisement