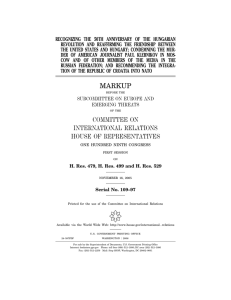

( IN DEFENSE OF HUMAN DIGNITY: THE INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT HEARING

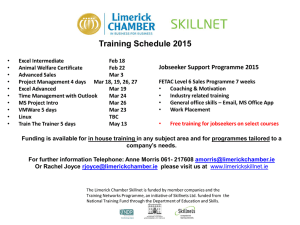

advertisement