( SAFETY AND SECURITY OF PEACE CORPS VOLUNTEERS HEARING

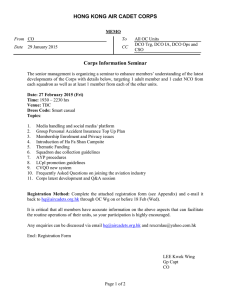

advertisement