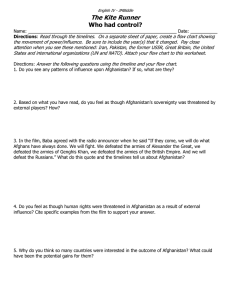

( AFGHANISTAN: UNITED STATES STRATEGIES ON THE EVE OF NATIONAL ELECTIONS HEARING

advertisement