FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY UNTIL RELEASED BY THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE

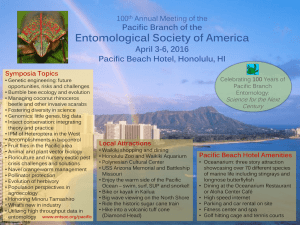

advertisement