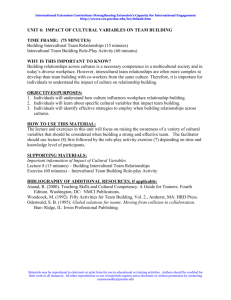

Internationalization in Action

advertisement