FM 3-04.240 ( ) FM 1-240 Instrument Flight for Army Aviators

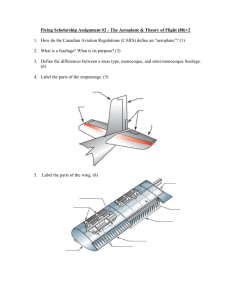

advertisement