Contact for further information about this collection

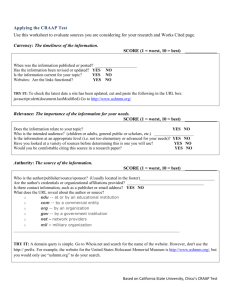

advertisement