Document 10709405

advertisement

--------~I------------------~~--------------------~

"\l~

30

• RITE S 0 F S P R I N G

.

.~~

PARIS·

~

31

mind at provocation. "It is success and only success, my friend," he .:~~

~tually

exclusive. A man obsessed with moralitL_,-'litlL.Sru;i!lJJy_a.c:- .

wrote to Benois in 1897, "that saves and redeems all " .. I do have al

·3P!~.QJe J)~h~iQr.,-cQ.uLd ne~~.r. be free, and like G.ide..2..-..Riv~~e!-_a~d

rather vulgar insolence and I am accustomed to telling people to goi¥~,

· Proust,

he ..believed

that.•.............•

the -artist,- to

""------_

__ -.. _------_

-_ achieve

_----_.-freedom

-_ _ of vision,

-.. _ must .

to hell." 18 He was a Nietzs~hean cr~ation, a supreme egotist out to

, have no +egar~Lfor.morality.

He must be<:7'-am.9.£a.~Morality, as the

c?nquer, and he suc~eed~d m becoming the?espot

of a cultural em- .~~ • avant-garde was w<?_~tto ..say:,_w.as-an .inventi.otLdgLlqids,··tnerevenge

plre that affected, pnmanly through the medium of ballet, all the arts"4~1

oftFie ugly. Liberation to beauty would come not th~ou-gficolkctive--'

of his time, including fashion, literature, theater, painting, interior ~

aforCout

through egotism, through a personal salvation and not

design, and even cinema. Jacques-Emile Blanche called him a "profes-';~

through social works.

sor of energy, the will that gives body to others' conceptions."

Although Diaghilev paid homage to history and the accomplishBenois was to say "Diaghilev had in him everything it takes to be a llf

ments of western culture, he did see himself essentially as a pathfinder

duce," 10 His public importance was in his achievement as.a manager,:;~

. and liberator. Vitality, spontaneity, and change were celebrated. Anyas a propagandist,

as a duce, and less as a creati~e person. As a ;1:

thing was preferable to stultifying conformism, even moral disorder

theorist he plundered other people's ideas; as an impresario, he plun-;~

. ;;;q.(;onf~~Xcin~bscar Wilde's sally that "there is no sin e~cept-s-tup;r

"

dered, in Napoleonic dragonnades, the world of art. His creation. was;~

express~(rDia~hiley~s:sentiments.

too-."$"QdaL~_o.d.....m:p_(aLabsoLutes_,

his management,

his shaping of shapes, and in this role he was a:~

~~~_~.t~r_().wn.Qverboard, and art, or the aesthetic sense, became the I..

brilliant artistic condottiere. As such he became central to twentieth.~; · jssue of supreme importance because it would lead to freedom.

.

."

~

century aesthetic sense, to the enshrinement of attitudes and styles:~

Diaghilev was of course merely a part, though an immensely signif- ~

rather than substance. He was a figurehead of the aesthetics of tech- i?6,

icant one, of a much broader cultural and intellectual trend, a revolt

nique. People wrote long letters to him; he replied by telegram.

against rationalism and a corresponding affirmation of life and expeThis does not mean, however, that Diaghilev did not have a posi- ;~

rience that gained strength from the 1890S on. The romantic rebelrive view ofart, He did, but his approach was intuitive, not analytical.

~.

lion, which, with its distrust of mechanistic systems, e~tended back

Many have noted how he would seize upon an idea or project imme- '.~.

..

over a century, coincided at the fin de siecle with the rapidly advanc7 diately,

before he had had an opportunity to examine it. While the :~

ing scientific demolition of the Newtonian

universe. Through the

.World of Art journal forced him constantly to formulate aestheticf~

discoverie~ of Planck, Einstein, and.Freud; (a.~iof1'!lma!l_l,ll1aermtn·ed·~ideas and to make decisions on the basis of these ideas, he never;~,

hi~ ..9.WILwQrld-:-Scle~~~ seemed thus to confirm important 't~ndendes

succeeded in assembling a clear and consistent philosophy of an. He '~

in philosophy and art. Henri Bergson developed his idea of "creative

did, nevertheless, build on certain premises.

,~:

evolution," which rejected the notion of "objective" kno~Tecfge: the

He conceived of art as a means of deliverance and regeneration.~.

reality is the elan vital; the life force. He became a veritable star

The deliverance would be from the social constraints of morality and .:~

in fashionable circles in Paris. And the Italian futurist Umberto Bocconvention, and from the priorities of. a western civilization - of .~

cioni, reflecting the widespread preoccupation

'with machines and

which Russia was. becoming increasingly a part - dominated by ai',

change, declared, "There is no such thing as a nonmoving object in

competitive and self-denying ethic. The regeneration would involve

}.~i

our modern perceptionof

life." Diaghilev was attuned to these develthe recovery of a spontaneous emotional life, not simply by the intel-~i

opments, which hailed 'a will t~ constant metamorphosis

~1ll~.d_~

[ecrual elite, although that was the first step, but ultimately by society

~

the beauty of transitoriness. He grasped the new wave with exhilara~.

.------- •.-,-~---.."".~..,

tiori:·"Q1}j-"!.'.E..vanc{!..p.a?.!f!.~yl~.i~~~~_9.eci9.~Q.-"

\.;-. as a whole. ~r~'.in t.~iS,outlook, is a li.f

..e .for~.:": .it has. the. inv.igorating

Ii, power of religion, It acts through the individual but m the end IS . II

In this context, where rationalist notions of cause and effect were

greater than thatindividual,

it is in fact a surrogatereligion.

,:',

rejected and the importance of the intuitive moment stressed, shock

f '..--..Social conscience did not "illOtlvate this th.inking. Like Nietzsche,

Diaghilev believed that autonomy of the artist and. morality w~re

• He who does nor advance retreats.

,I

~ ... .--- .

19:~1

itY"

I

ani;;-

f

~

'I~

"i

~j,

,"I'

jr~!

~~~!

~ifi

-. .

~...--=->

o.

._

,-_.~_

__

;'fi:itl~

'l:~

32 • RITE 5 0 F 5 P RI N G

..

11,

PA RI S • 33

and provocation became import~nt. instrum~nts of art. For ~iaghilev .~.

art was not meant to teach or Imitate reality; abovealJ, It was to;1

provoke genuine experience. Through the element of shock he hoped ~~,

to achieve in his audience what Gide tried to elicit from his protago:;

nist Lafcadio in Les Caves du Vatican, which was published in 1914:~1

an "" gratuit, behavi.or free of motivation, p~rpose, ~eaningj pure~1

action; sublime expenence free of the constrarnrs of time or place. ~~

"Etonne-moi, [ean!": Diaghilev said to Cocteau on one occasion,;}~

and the latter came to look on that moment and utterance as a road- .~

to-Damascus experience. Surprise is freedom. The audience, in Dia- .)~

ghilev's view, could be as important to the experience of art as the . :~I

performers. The art would not teach - that would make it subser- ;11

vient; it would excite, provoke, inspire. It would unlock experience.

.

In his belief that art had to draw more of its content from popular ~

folk traditions and that only in this way could the gap be bridged .1-'.'

between popular and high culture, Diaghilev followed in the footsteps

of Rousseau, Herder, and the romantics. It was in the Russian countryside, primitive and unaffected by mechanization,

that Diaghilev

and his circle found much of their inspiration, in the designs and

colors of peasant costumes, the paintings on carts and sleighs, the

carvings around windows and doors, and the myths and fables of an

unassuming rural culture. It was, according to Diaghilev, from this

Russian soul that salvation would come for western Europe. "Russian art," he wrote in March 1906 before his first exhibition there,

"will not only begin to playa role; it will also become, in actual fact

and in the broadest meaning of the word, one of the principal leaders

of Our imminent movement of enlightenment." 21

:t~

;t~

Diaghilev acknowledged

his intellectual debts: to a conservative

Russian culture rooted in an aristocratic tradition; to a wave of modern thought that stretched back a century and thar had a strong

German component, in E. T. A. Hoffmann, Nietzsche, and Wagner,

among others; and to a growing appreciation, particularly in Russia,

Germany, and eastern Europe, of what the Germans called Volk

culture.' But while he possessed a strong sense of history, his sights

were set on the future. He followed the manifestoes and exploits of

the futurists with interest, and showed a special fondness for the art

of the Russian futurists Larionov and Goncharova. He did not de• Surprise me, Jean!

spise technology as some aesthetes did but looked on the machine as

.a central component of the future. On New Year's Day 19I 2, Nijin...sky and Karsavina danced Le Spectre de la Rose at the Opera in Paris

. at a gala honoring French aviation. As an impresario, Diaghilev was

keenly aware of the importance of modern methods of publicity and

..advertisement, and he had no compunction in resorting to exaggera,·tion, ambiguity, and impertinence in his pursuit of success.

, The goal of his grand baIJet was to produce a synthesis - of all the

arts, ofa legacy of history and a vision of the future, of orientalisrn

andwesternism,

of the modern and the feudal, of aristocrats and

peasants, of decadence and barbarism, of man and woman, and so

on. He wished to fuse the double image of contemporary

life - an

age of transition - into a vision of wholeness, with emphasis, however, on the vision rather than the wholeness, on the quest, the striv.jng, on the pursuit of wholeness, continuing and changing though

..this had to be. He meant, in Faustian temper, to overcome and integrate -. The "either-or"

decision that ethics called for he rejected in

, favor of an aesthetic imperialism that, like Don Giovanni, craved

., everything. Here was a hunger for wholeness that nevertheless, be·:cause of its emphasis on experience, celebrated the hunger more than

, the wholeness ..

REBELLION

Diaghilev's ballet enterprise was both a quest for totality and an

;. instrument of liberation. Perhaps the most sensitive nerve it touched

l . _ and this was done deliberately - was that of sexual morality,

.which was so central a symbol of the established order, especially in

the heart of political, economic, and imperial power, western Europe.

Again, Diaghilev was simply an heir to a prominent, accumulating

tradition. For many intellectuals of the nineteenth century, from

Saint-Simon through Feuerbach to Freud, the real origin of "alienation," estrangement from self, society, and the material world, was

sexual,' "Pleasure, joy, expands man," wrote Feuerbach; "trouble

suffering, contracts and concentrates him; in suffering man denies the

reality of the world." 1

The middle classes', in particular, of the Victorian age interpreted

pleasure in primarily spiritual and moral rather than physical or sen-

'{.

i.i

..

,

':.1'

'. P I< f~")s:

. ,f:· a.4

I

'f

~-u;J

'f

~.

·1

i

",

iI

*

i

i

!

,.i

I

I

· .

· ..,

'.'

,l

.

'.

i:

,

.,

..

.~ '

·:

[T

•..••

I

·,,,·,·,·

..··;l'f'··,.·'··,"

I :\;~'f;' "'1'.

.(t~-c ••",t;7,'_!,

'.' ::if ;:: ·~);·~lh.:::.:~t~

:fi'..

;'l'f;,·JI"'.' !+Tlf;

.;';r;

,f.;"", ..)i:;,

HIS volume is issued in the belief that Eng1isbi~:;';L~M::;:

•.;'.:.;;}:~

.' oet

IS now once a am

uttm on a. newl~:\:;:i'h '. ;'j"~

.stren 1 an eaut.

."

i .

:&'

.

.cw rcadersl1ave·the leisure or the zeal to investigate (.~r:::::~!r

.. iFf;

each volume as it appears; and the process of recog-;:; .. ,.;:i;j'i?:)iji

..

• f

1

Thi s co11.n!

. 1y:'{:':"'~;:;~~(':'

.... '.... ~\......•

'\.

ninon

IS 0 ten sow.

ecnon, d rawn entire

:.;?~,::

from. the publications of the past two years, may if it;! .:)}It.,:' <.;;;,~

is fortunate help the lovers of poetry to realize that wer:';:~;';:~;: : .::'.;X

arc at the

'n'

0

no er"

0 ian

eriod "X:· . ,';"'(':;. .:' ;:i'-i

Ir. which'

take rank in due time with he s y~re

t},

'{k~

•

DEDICATED

TO

ROBERT BRIDGES

BY THE WRITERS

AND THE EDITOR

••

. I,..•

·..• ;.,.....,.:.

"iL

l\~

",

•• ,j

,".'.'1: t>JJ!i" ';'..~~I'1}!JH

;;:r~~

. :!,:.":·~~~f ~;~\;i:~l':'~

.

I

.

'li'ii':4iiIi~

!'.\H~~l1k

.

,

,.~,. U':Vhn" ~ ';""":*'

PREFATORY NOTE TO FIRST EDITION

I

~

::I:.+'}:.

-n :

I

.-r&~'"

..

.' ,

.'

]

,-: ~"

-.+~Hh ~>;

~~X;i'ltlU.i

. ' ...

?

'''.

·.~~iF·"::\];:llt;>;ri

' It has no pretension to cover the field. Every reader;':; . ':):nt#"~i;:'~:

will notice the absence of poets whose work would be 1l:::."'·:9 ;:;".:}~

ncccssary ornament of any anthology not limited by a:,'; ".:;;\(J;l, .,)

definite aim. Two years ago some of.the writers repre-Y. .•

scnted had published nothing; and only a very.few of:., ·"Li\!.H' .d

the others were known except to the eagerest" watch~.·":'"!);f~~~

5!:::.;::;t

ers of the skies." Those few are here because within the .:. .':; 'l:~~

: . ..'t

chosen period their work seemed to have gained some::i:::;~'{~r!.:.

accessionof power.

.

.. ..': ';;1'f;:r.-:

:My gratef~ thanks are due to the wr~ters who have:;\::~:::i~~Ji:

lent me their poems, and to the publishers (Messrli";'j:.Lj

'.

Elkin Mathews, Sidgwick and Jackson, Methuen, Fi~r~ :~i;i;~."f·

field, Constable, Nutt, Dent, Duckworth, Longmanli;;:~' .':l;;:~!,

and Mau?sel, an~ the Editors of BasJleon! Rhythm, anq ,[;: ;.l~~tj:

the EnglISh Ref/Jew) under whose unpnnt they hav~ :.f! :

appeared.

" "~C • ~qtp'j; - ';.,

::+!~:Ji.' :~:

.'":

>t;:1~;. .

lZ

Oct. 19

E.

.,(

M'!~il~Mi',

.";;j

.r.

.

l \ "' ...•...

~I(~~

''; , "";:~

i:J.t

1t:~~~~n~'.~ ~ii:»

/.'1..' , l\.~141',I.. r;'~

\/t:l~1

, Ik

.,

"i~f'~}f'~' ':"r;t

rj)fJ:h. ·....

l~·

::

. '.,

(.

•

w .'

t·

~':·~

..L...._.

_-"f'gtiil:ij(j'il"IM~~~~~id';'<""';~";:";:';";:;'

I~

.~l{'i>

72l~.94

...

,',

·

~~

);.

'.:,

.':

'

.

.:

r.;< '.;~h~::'

.:~::

. . '.::~~

j I~'I/'..~~:'',~':

i

f

~

:':'<:1:",

••••

~Jf!{~~(~\:':

:',':

. i'··I,!.'

,<

l)m;'::: ' .

l

;:li'h:,:.:'

~;'·.<~!m!.2'~

\'.','"

'.~.:"

:.';:.

,'.;:\:~,,,:;,~:

...

:,~.'l(~jl'~hi!i

~r

'. 'Hl" ,~f"Y i.X!~tl1J·;.;~tJ~~~k~l~a

,i.-"

'l'l'P"-",

~ 0 , "1

,.~Wi:'-: Jrj."....

,\

'"

~

'I

:,i:1I'i!:"

,.1;>":t~

.:!!)

W

~t

",:

I'

.'"

'.

•

PREFATORY NOTE

' ,

\,;,

'

'.' .

.tr» \,.

""il~U~~I~l

~: ~( ,~,?'~;r/T~;A

" ;;,

,I"

.1:;,:.

.,

':'-P'~~~f~··'l)i((j

HE~ the fourth volume of this Benes .,,:a8...:::,',:M~\.~~JN\9~

published three years ago, many of the crltics] .: ..:':: :',::.)!

who had up till then, as Ho~ace Walpole 'said of God,. );j\l('\(:;ij:~{

t been the dearest creatures In the world to me, took

.' ';:it ):?';H

another turn. Not only did they very properly

,:;;' '; /~:\

dirsapprove my choice

. 0f poems: t hey went on to ,.·:);Wo;,J:i!;

.... ,.."

ifu

write as if the Editor of Georgian Poetry were a kind of,'::~:

':\:~1

',: public functionary, like the President of the Royal

;ir:L;;ii~li

. Academy; and they asked-again, on this assumption;

.,' very properly-who was E. M. that he should bestow

..}i;;!' .

." and wit?hold crowns and sceptres, and decide that this;\ilr'J:

or that poet was or was not to count.

"

' ...

,', This, in the words of Pirate Smee, was 'a kind oj a .

(omplin/wl, but it was also, to quote the. same hero,

galling j and I have wished for an opportunity' of

, disowning thepretensionwhich I found attributed to

me of setting up as a pundit, or a pontiff, or a'

Petronius Arbiter; for I have neither the sure taste,

\11

nor the exhaustive reading, nor the ample leisure

" which would be necessary in a'ny such role.

The origin of these books, which is set forth in the'

memoir of Rupert Brooke, ~

I,

found, ten years ago; that there were a number of

,.; writers doing work which appeared to me extremely

'. good, but which was narrowly known; and I thought

.. t?at anyone, however unprofession~l. and meagr.ely" .::t :;,i~;Jl

gIfted,who presented a ~onspectus.of It m a challengmg:';:<1:r.til~:~~

and manageable form might ?e domg.a good turn ~oth.

'j!~f:'

" to the poets and to the reading public, So, I think I ..',; ,;\"', ,:~\\~

,:~ may claim, it proved to be. The first volume seemed

. :US>··:\t.i(j

,:;,

to

supply

a

want.

It

was

eagerly

bought;

the

',con-,"

:',:,{:i:'ih)}

s.

"

\

N tinuation of the affair was at o~ce taken so much for

~:fgranted as to be almost unavoidable ; and there has" 'j ,::J~;

l

TO

ALICE

,

"1

,,;>0 ~

~I.~,;~.~

,'" :',:::''." ':.:;';.':,,,

-',,~:~~<~J::8f

",', C-;'; ..:' -:.':.":',~.

,

'

,~

','.1 .• , .,:~- ":",".".·.:t·, :'/.~ ..~:;.~'" Pi~:/':'·!.\:tim~ft:

.

MEYNELL

",;'li!!j(:f,j~

'!j

..

'I

lj

.>.

~~ ...

. .~

.. '

.'

1!

••

~1

. . ..

.~

4

.

•. .•

•

•

•• '~

"

"

Ii

..

IiI

. ' i; ..

j:

."

"

~t-:>

'

~~\'t\"

3ft

I

;'·:'.',ik·j'·Y:,'"

li,llf:

,I, .. ,

.••...

jI·

~i

*.

\

0'

...;

I

l.\

.: "

•

•

C) ~

9

.',;

,:1

:J,'.

I'

a:~l.!~~;n;;,::'\: ;'

: ;,

Ill~'"i:'~b':"!',"',,'

~Uji

/k: r~l~\fr

t f.<

~~f' .:':< ,~:\f~

.....

jl:-\I~'l!i;ii."f~

"

);rt~

I.

,Mllde 11114prinl" in Grelll Brilabi.,

.~

-!.

t,

:f

,:':::A~t,f~:S~

j";

,b~',lk,:".;':\'"

?

-,

•

.. r'

: ; •t, ~.

,)i;: ~l;\;(':

,;~:~~F:

:L> ~

1"'~' "I'.V.~~I

:::~"~!;~f:

:i~c;;

.,'\~"fI

i'

:::..

fJ·

"

.

r.

k.

r:

been no break in the demand for the successive books.

If they have won for themselves any position, there is \;:

no possible reason except the pleasure they have given. :

Having entered upon a course of disclamation, I!

should like to make a mild protest against a further t·

charge that Georgian Poetry has merely encouraged a f

small clique of mutually indistinguishable poetasters F'

to .abound in their own and each other's sense or;'

nonsense. It is natural that the poets of a generation h

should have points in common; but to my fond eye) .

those who have graced these collections look as diverse k

as sheep to their shepherd, or the members of a i:

Chinese family to their uncle; and if there is an i::

'. allegation which I would deny with botb bands, it is ~;

this: that an insipid sameness is the chiefcharacteristic f .

of an anthology which offers-to name almost at b

random seven only out of forty (oh ominous academic it

number I)-the work of Messrs. Abercrombie, Davies, t·

de la Mare, Graves, Lawrence, Nichols and Squire.

The ideal Georgian Poetry-:a book which would err L

neither, by omission nor by inclusion, and would I:

contain the best, and only the best poems of the best,

. and only the best poets of the day-could only be :,

achieved, if at all, by dint of a Royal Commission. 1

The present volume is nothing 0.£ the kind. ,.

.

I m~y add. one word bearing on my aim m

selection. Much admired modern work seems to I'

;f-!me, in its. lack of inspiration and Its disregard of

form, like gravy imitating lava.. !ts upholders may

retort that much of the work which I prefer seems .;

, to .them! in its~ack ~f ~nsRiration and its.compa~ative

,fimsh, like tapioca mutatmg pearls. Either vrew=possibly both-may be right. I will only say that

with an occasional exception for some piece of ,;.

rebelliousness or even levity which may have taken .1

}~~

my fancy, I have tried to choose no' verse but such'~

as in

,

~~:d~;~~::~~

~~~~~

accept

Wit.h cad

.

s, s 'le, deliberately

p~, %-';:p~

lease.d.

.

There are seven new-corners-Messrs. Armstr g,

Blundcn, Hughes, Kerr, Prewett and Quenn ,and~

Miss Sackville-West. Thanks and ackno edgments

arc due to Messrs. Jonathan Cape, Cha~and Windus,

R. Cobden-Sanderson, Constable,

. Collins, Heinemann, Hodder and Stoughton, Jo Lane, Macmillan,

Martin Seeker, Selwyn and

ount, Sidgwick and

Jackson, and the Golden

ckerel Press; and to the

Editors of The Cbapbo , Tb» London MerCflf'Y and

'I be TVeJt1izimter Ga te,

E. M.

r

',i

,

~.£

'(l.<Y~'t.S'

~f,,'

'~ ~

.

·1:"

:{

C~J~ J# ViP

JUl~~

+

r\

I;

J~"~

~/

!.

Ii

fl.

k

1\

II

I

,f

'f,

l

I

'r~

'\

.----; .--:---.-.-

"

',',"""

..~.--.-_.,..

""

r----

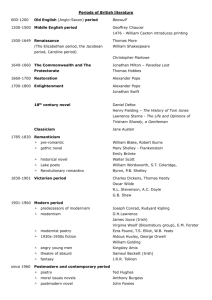

Georgian Poetry: originally the title of a series of live

poetry anthologies produced between 1912 and 19:u.

the term is more generally applied to predominantly

rural and stylistically conventional verse of the·kind

the books tended to contain. The series was conceived by Edward ·Marsh, who proposed to invigorate English poetry at a time when it remained

dominated by late Victorian reputations: the title

Georgian Poetry reflected the enthusiastic: sense of a

new era that accompanied the accession of George V

in 1910. Rupert oBrooke, strongly favoured by Marsh

and regarded as a leading Georgian, publicized the

venture and Harold "Monro acted as publisher. In .

commercial terms-the seriCS·'W2S·highly:succ6SfuL ,: ..-:.:.

The following were eminent among the total of

thirty·six poets who contributed to the anthologies:

Lascelles "Abercrombie, Gordon -nottomley, W. H.

·Davies, Walter =de la Marc, Wilfrid ·Gibson, Ralph

"Hodgson, james -Stephens, and Andrew "Young.

While these and others produced work of note, the

pedestrian rhythms, rural sentimentality, and imaginative banality of much of the verse has given 'Georgian' a distinct pejorative sense in the modem critical

vocabulary. The blank verse dramas contributed by

Abercrombie. Bottomley. and Gibson were among

the most interesting material published in the series.

Although

the anthologies

contained

'Work by

Edmund "Blunden. Robert "Graves, and Siegfried

·Sassoon. the most talented of the younger Georgian

poets. Marsh did not publish any of the more disturbing examples of their "war poetry: objections to the

constraints imposed. by his taste were voiced by

Graves and Sassoon, the latter choosing not to be represented in the final volume· of the series. D. H.

"Lawrence was another contributor who disagreed

with Marsh's fundamentally

conservative views on

questions ofform and content. After Marsh discontin·

ued the series in 1922, coincidentally but aptly the year

in w hich The ·V\'Q.J1r lAnd appeared, J. C. "Squirc·s

Londoll Mereu!)' provided a platform for Georgian

verse, and a target for its detractors, for whom it represented the antithesis to poetic "Modernism. F.

Swinncrton's

TIlt- Georgian L,iterary Scene, 1910-1935

(1950) surveys the social and cultural contexts of Georgian poetry,

..

..

humanist

tradition.

(1920), Eliot's

The

Pound's Hugh Selwyn Maubrrlry:

-WQ.J[eLattd (1922). Woolfs'acob's·

"

•••

C ••••••

R:ocn:,(I~~),a~d)?yce'~~ysscs

(1922) are among the

works w'ludi indicate the breach with the conventions of rational exposition and stylistic decorum in

the inunediate post-war period.

~~erimental.techniques

become a distinguishing

trait of Modernist texts between approximately 1912

and 1930. the period of what is sometimes referred to

as 'High Modernism', Among the strategies used to

reinterpret experience in the novel were the '"stream

of consciousness'

mode, ·narrative discontinUities,

shifting authorial perspectives, and effects of montage

and collage comparable to innovations in the cinema

and painting, Similar procedures were introduced into

poetry through the extended poetic engagements

with personal experience, history, and contemporary

conditions in The Wasre Land and Pound's early drafts.

of The "Clntos (1917-33), These works demonstrated

":-:,.,,,.:"~~::;,!~,t~~~~s;:;:::iLji~~~;'~~;~:~·:;:;:m~.~

••;~;;~~<'f.c;··:··

the possibilities for poetry's freedom from ~e conStraints of orthodox thematic development. metrical

determination,

and the distinctions between lyrical

and expository idioms. °lmagism'~ emphasis on .

clarity, concentration, and tile essential functions of

the image revised poetic theory and practice in Britain .

.and America from around 1912 onward, The use of

myth as a structural device is common to numerous

definitive texts, most notably Ulysses, The WQ.J[( Land,

and TIlt" Call1os;the energelic sty list ic mobility evident

in each of these exemplifies the high degree of aesthetic self-consciousness ofiiterary Modernism. Edith

·Sitwell, Pound, and Wyndham ·Lewis were among

the Modernist writers noted for polemical hostiliry

towards conservative authors, a quality often evident

in the oljttle magazines with which they were associated; the vigour with which the)' rejected conven- !...,.::'..

tionalliteraturc

arose from the urgency of the need

they felt to sever connections with a culture the war

had proved a failure. The Modernists' disregard of the

expectations of a common readership resulted in allegations of obscurity and elitism which remain central

to critical debate. Modernism has been, and remains,

widely pervasive in its influence; it has engendered a

multiplicity of approaches to matters of literary form

and content that have affected writing in English,

whether obviously or subtly, on almost every level.

A Survey of Modernist Poetry (19~7) by Robert

°Graves and Laura ·Riding, which established a finn

distinction between 'modern' and 'modernist', is one

of the earliest extended studies ofliterary modernism,

The Modan Tradition: BackgrOllndsofModan Literat1J.re

(1965, edited by. R. "EUmann and C. Fcidelson)

remains' valuable as an anthology of Modernist documents, Modernism (1976, edited by M. OBndbury and).

McFarlane) offers a comprehensive critical survey.

Among the many studies available arc H. Kenner's

Th~ Pound Era (1971), S, Schwanz's The Matrix ofMod.

ernism (1985), A, Gelpi's A Coherent Splendor: The Amer.

ican Poetic Renaissance, J91~1950 (1988), and B,

Bcrgonzi's

The M)1h of Modmlism alld Twcnricth

Cent1J.ryLileralllr( (1986), See also SURREALISM.

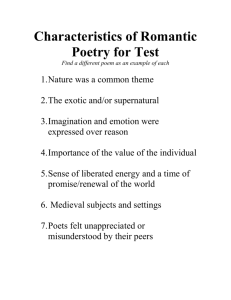

Modernism,

a term encompassing numerous movements characterizing international developments in

literature, music, arid the graphic and plastic arts from

the late nineteenth century onward. Most cornrncntators consider literary Modernism's typifying manifestations in English to have appeared between 1890

and 1930, Among the authors most frequently cited

arc joseph 'Conrad, T, S. ·Eliot, William "Faulkner,

Ford Madox "Ford, James "joyce, D, H. "Lawrence,

Ezra ·Pound. William Carlos "Williams, Virginia

"Woolf, and W. B, "Yeats; European writers associated with Modernism include Bertolt Brecht. Andre

Gide,

Franz Kafka, Thomas

Mann,

Vladimir

Mayakovslcy, Marcc:l Proust, and Rainer Maria Rilke,

while Charles Baudelaire,

Gustav Flaubert, and

Arthur Rimbaud are regarded as three of its principal

progenitors. The experimental qualities thought of as

essentially Modernist are found in the writings of

many of the above: others are more traditional in

their stylistic and narrative practices. All, however,

respond acutely to the radical shifts in the Structures

of thought and belief that were brought about in the

fields of religion, philosophy, and psychology by the

works of Sirjames °Frazer, Charles Darwin, Friedrich

Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and others. The moral

cataclysm of the First World War accentuated the

senses of general cultural catastrophe and individual

=piritual crislsapparcnt

in the writings of novelists

end poets already sensitive to such disruptions in the

- - .--~.-----

Modem Utopia, A

~:;,.: ,,-,.::-,,:.,'

.,'

..•.

:-

":~".

~.

-,

Cyclic Drama

~

130

D

the Cyclic Poets. Other examples of cyclic NARRATIVE

are the Charlemagne

EPICSand Arthurian ROMANCES,

such as the "Cycle of Lancelot." The MEDl-.

EVAL religious DRAMApresents a cyclic treatment of Biblical THEMES.

Cyclic Drama:

PLAY;

The great CYCLESof MEDlEV

ALreligious DRAMA.See MYSTERY

Cynghanedd: Originally a medieval Welsh term covering a wide and sophisticated range of VERSEdevices, the term was revived in the late nineteenth

century by Gerard Manley Hopkins to refer to various harmonious patterns

of interlaced multiple ALLITERATION

(see CROSS-ALLITERATION).

Simpler sorts

of alliteration are linear and unilateral-as in the common American lunchcounter order "A cup of coffee and .a piece of pie" or Keats's deliberately

archaistic line" A shielded scutcheon bl ushed with bl ood of queens and kings."

Interlacing alliteration, however, in such patterns as xyyx and xyxy (much

the commonest), produces a quadratically ornate effect, such as sometimes

occurs in vernacular phrases ("tempest in a teapot," "partridge in a pear

tree) and the Biblical collocation of swords-ploughshares and spears-pruninghooks. There is conspicuous and complex cimghanedd in Macbeth'sdescription

of life as a "tale I Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, I Signifying

nothing" and in Wordsworth's noble tribute to Milton: "... and yet thy heart

I The lowliest duties on herself did lay." As noted, instances of cunghanedd

turn' up in the vernacular and in PROSE(as in the phrase "toothpaste and

toilet paper" in Thomas Heggen's Mister Rohertsand Faulkner's vivid evocation of a hog's gait as a "twinkling purposeful porcine trot"), but the most

distinguished, varied, and engaging employment remains that in almost all

of Hopkins's mature POEMS.The most salient such use is in the sonnet beginning "As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies araw flame" and the end of

"God's Grandeur":

.

Becausethe Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! b"rightwings.

Cynicism: Doubt of the generally accepted standards or of the innate goodness of human action. In literature the term characterizes writers or movements distinguished by dissatisfaction. Originally the expression came into

being with a group of ancient Greek philosophers, led by Antisthenes' and

including such others as Diogenes and Crates. The major tenets of the cynics

were belief in the moral responsibility of individuals for their own acts and

the dominance of the will in its right to control human action. Reason, mind,

will, and individualism were, then, of greater importance than the social or

political conduct so likely to be worshiped by the multitude. This exaltation

of the individual over society makes most unthinking people contemptuous

of the cynical attitude. Any highly individualistic writer, scornful of accepted

social standards and ideals, is, for-this reason, called cynical. Almost every

literature has had its schools of cynics. Cynicism is not necessarily a weakness

or a vice, and the. cynics have done much for civilization. Samuel Butler's

Way of All Flesh and W. Somerset Mangham's Of Human Bondage. are examples of the cynical NOVEL.The THEATEROF THE ABSURD,the THEATEROF

CRUELTY,and many ANTIREALISTIC

NOVELSof today reflect cynicism of one

sort or another.

Dactyl: A FOOT consisting of one accented syllable followed by two unaccented, as in the word mannikin.

See METERand VERSIFICATION.

Dadaism: A movement in Europe during and just after the First World War,

which attempted to suppress the logical relationship between idea' and statement, argued for absolute freedom, held meetings at bars and in theaters,

and delivered .itself of numerous nonsensical and seminonsensical manifestoes.

It was founded in Zurich in 1916 by Tristan Tzara (who then went to Paris)

with the ostensibly destructive intent of perverting and demolishing the tenets

of art, philosophy, and logic and replacing them with conscious madness 'as

a protest against the insanity' of the war. Similar movements sprang up in

· Germany, Holland, Italy, Russia, and Spain. About 1924 the movement devel· oped into SURREALISM.

In certain respects it seems to have been a foreiunner

of the ANTIREALISTIC

NOVELand the THEATEROF THE ABSURD.

[References: C. W. E. Bigsby, Dada and Surrealism (1972); Mary Ann

Caws, The Poetry of Dada and Surrealism (1970); Alan Young, Dada and

· After: Extremist Modernism and English Literature (1981).]

Dandyism: A literary STYLEuSedby the English and French DECADENTwriters of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The term is derived from

dandy, a word descriptive of one who gives exaggeratedly fastidious attention

to dress and appearance. Dandyism as a literary STYLEis marked by excessively

refined emotion and PRECIOSITY

of language. One or another species of dandyism has been associated with the life or work of Byron, Poe, Wilde, Wallace

Stevens, 'and James Merrill, as well as a long succession of French writers

from Baudelaire to the present. A somewhat more subtle and profound ideology than superficial emphasis on the sartorial may suggest, thoroughgoing

dandyism reflects a preference for culture over nature, city over country,

" manner over matter, surface over substance, and art over life.

Dark Ages: The medieval period. Use of the term is vigorously objected to

by most modern students of the Middle Ages, since it reflects the now-discredited view that the period was characterized by intellectual darkness-an idea

that arose from lack of information about medieval life. The period, as a matter

offact, was characterized by intellectual, artistic, and even scientific activity

that led to high cultural attainments. Most present-day writers, therefore, avoid

. using "Dark Ages." Some who do use it restrict it to the earlier part of the

Middle Ages (fifth to eleventh centuries).

[Reference: W. P.Ker, The Dark Ages (1904, reprinted 1979).]

Dead Metaphor: A FIGURE OF SPEECHused so long that it is now taken in

its denotative sense only, without the conscious comparison or ANALOGYto

a physical object it once conveyed. For example, in the sentence "The keystone

of his system is the belief in an omnipotent God," "keystone"-literally

an

actual stone in an arch-functions as a dead metaphor. Many of our ABSTRACT

- J. 11

ra g,U

Hi

uun

::>l

;::;)U

251

~

Imitation

world that is presented through the language of the work; on the rhetorical

patterns and devices by which the T.ROPESin the work are achieved; on the

psychological state producing the work and providing its special and often

hidden meaning; on the ways in which the pattern of its IMAGESreinforces

(or on occasion contradicts) the ostensible meaning of discursive statement,

PLOT, and ACTION in the work; or on how the IMAGESstrike responsively

on resonant points in the racial unconscious, producing the emotive power

of ARCHETYPESand MYTH. See IMAGE, METAPHOR,FIGURATIVELANGUAGE,

NEW CllITICISM, ALLEGORY.

the function of which is to give art its special authority, the assumption is

almost always present that the "new" creation shaped by the imagination is

a new form of reality, not a FANTASYor a fanciful project. When Shakespeare

writes

Imagination:

The theories of POETRY advanced by the romantic critics of

the early nineteenth century (Wordsworth, Coleridge, and others) led to many

efforts to distinguish between imagination and FANCY, which had formerly

been virtually synonymous. The word imagination had passed through three

stages of meaning in England. In RENAISSANCEtimes it was opposed to reason

and regarded as the means by which poetical and religious conceptions could

be attained and appreciated. Thus, Bacon cited it as one of the three faculties

of the rational soul: "history has reference to the memory, POETRY to the

imagination, and philosophy to the reason"; 'and Shakespeare says the POET

is "of imagination all compact." In the NEOCLASSICPERIOD it was the faculty

by which IMAGESwere called up, especially visual IMAGES(see Addison's The

Pleasures of the Imagination ),and was related to the process by which "IMiTATION of nature" takes place. Because of its tendency to transcend the testimony .

of the senses, the poet who might draw on imagination must subject it to

the check of reason, which should determine its form of presentation. Later

in the eighteenth century the imagination, opposed to reason, was conceived

as so vivid an imaging process that it affected the passions and formed "a

world of beauty of its own," a poetical illusion that served not to affect conduct

but to produce immediate pleasure.

The romantic critics conceived the imagination as a blending and unifying

of the powers of the mind that enabled the POET to see inner relationships,

such as the identity of truth and beauty. So Wordsworth says that poets:

his reference is properly made to imagination, not to that power of-inventing

the novel and unreal by recombining the elements found in reality, which

we commonly call FANCYand which expresses itself in FANTASY.See FANCY.

[References: J. W. Bray, A History of English Critical Terms (1898);

R. L. Brett, Fancy and Imagination (1969); Denis Donoghue, The Sovereign

Ghost: Studies in Imagination (1976); J. L. Lowes, The Road to Xanadu: A

Study in the Ways of the Imagination (1927, rev. ed. 1955); l. A. Richards,

Coleridge on Imagination (1960); Jean Paul Sartre, Imagination: A Psychological Critique (tr. 1962).]

Have each his own peculiar faculty,

Heaven's gift, ·a sense that fits him to perceive

Objects unseen before , ..

An insight that in some sort he possesses, ...

, Proceeding from a source of untaught things,

This conception of imagination

necessitated a distinction between it and

FANCY,Coleridge iBiographia Literaria) especially stressed, though he never

fully explained, the difference. He called imagination the "shaping and modifying" power, FANCY the "aggregative and associative" power. The former

"struggles to idealize and to unify," while the latter is merely "a mode of

memory emancipated from the order of time and space." To illustrate the

disti~ction Coleridge remarked that Milton. had a highly imaginative mind,

Cowley a very fanciful one. Leslie Stephen stated the distinction briefly,

"FANCY deals with the superficial resemblances, and imagination with the

deeper truths that underlie them."

'

While imagination is usually viewed as a "shaping" and ordering power,

As imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns the;TI to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name,

Imagists: The mime applied to a group of POETS prominent in England and

America between 1909 and 1918. Their name came from the French title

, Des ltnagistes, given to the Brst ANTHOLOGYof their work (1914); this, in

turn, haying been borrowed from a critical term that had been applied to

some French precursors of the movement. The most conspicuous figures of

the imagist movement were Ezra Pound, Hilda Doolittle ("H. D."), and

F. S. Flint, who collectively formulated a set of principles as to treatment,

DICTIONS, and RHYME. The Imagist IMAGE, according to Pound, presented

"an intellectuall and emotional complex in an instant of time"-with

the intellectual component borne by visual IMAGES,the emotional by auditory. According to Amy Lowell's Tendencies in Modern American Poetry (1917), the major

objectives of the movement were: (1) to' use the language of common speech

but to employ always the exact word-not

the nearly-exact; (2) to avoid all

CLICHE expressions; (3) to create new RHYTHMSas the expressions of a new

mood; (4) to allow absolute freedom in the choice of subject; (5) to present

an IMAGE (that is, to be concrete, firm, definite in their pictures-harsh

in

outline); (6) to strive always for concentration, which, they Were convinced,

was the very essence of POETRY; (7) to suggest rather than to offer complete

statements. Pound soon dismissed Lowell's writing and crusading as "Amygism," but her labors did help somewhat in conditioning the public to accept

something new.As early as 1914, Pound moved from Imagism to VORTICISM,

the more kinetic movement, and eventually let the coinage PHANOPOEIAsupersede both IMAGEand Imagism.

.

[References: John T. Gage, In the Arresting Eye: The Rhetoric of Imagism

(1981); Glenn Hughes, Imagism and the Imagists (1931); W. C. Pratt, The

Imagist Poem (1963).]

-fmitation:

The concept of art as imitation has its origin with the CLASSICAL

critics, Aristotle said at 'the beginning of his Poetics that all arts are modes

of imitation, and he defines a TRAGEDYas an imitation of an ACTION of a

(challenges, defiances, boastings) of the ,HEROES; descriptions of warriors (especially their dress and equipment),

battles, and games; the use of the EPIC or

HOMERIC SIMILE; and the employment

of supernatural

machinery (gods directing or participating

in the ACTION). When the mock POEM is much shorter

than a true EPIC, some prefer to call it mock heroic, a term also applied to

poems that mock ROMANCES rather than EPICS. In ordinary usage, however,

the terms are interchangeable.

Chaucer's Nun's Priest's Tale is partly mock

heroic in character, as is Spenser's finely wrought Muiopotmos, "The Fate

of the Butterfly," which imitates the opening of the, Aeneid and employs elevated STYLE for trivial subject matter.Swift's

Battle of the Books is an example

of a cuttingly satirical mock epic in PROSE. Pope's The Rape of the Lock is

perhaps the finest l~ock heroic poem in English, satirizing in polished VERSE

the trivialities of polite society in the eighteenth

century. The cutting of a

lady's lock by a gallant is the central act of heroic behavior, a card game is

described

in military terms, and such airy spirits as the sylphs hover- over

the scene to aid their favorite heroine. A brilliantly executed mock epic has

a manifold effect: to ridicule trivial or silly conduct; to mock the pretensions

and absurdities of EPIC proper; to bestow an affectionate measure of elevation

on low or foolish CHARACTERS; and to bestow a humanizing,

deflating, or

debunking

measure of lowering on elevatedcha~acters,

[Reference:

Richmond

P. Bond, English Burlesque Poetry, 1700-1750,

(1932, reprinted

1964).]

Mode:

In literary CRITICISM a term applied to broad categories of treatment

of material, such as ROMANCE, COMEDY, TRAGEDY, or SATIRE. In this usage,

mode is broader than GENRE. Northrop Frye sees ROMANCE, COMEDY, TRAG, EDY,'and IRONY' as modes of increasing complexity.

in literature

(see FREUDIANISM and JUNGIAN CRITICISM), Its most interesting

, artistic strategies are its attempts to deal with the unconscious and the MYTHOPOEIC. In many respects it is a reaction against REALISM and NATURALISM

and the scientific postulates on which they rest. Although by no means can

all modem writers be termed philosophical

existentialists,

EXISTENTIALISM

has created a schema within which much of the modem temper can see .a

reflection of its attitudes and assumptions (see EXISTENTIALISM).-The modem

revels in a dense and often unordered

actuality as opposed to the practical

and systematic, and in exploring that actuality as it exists in the mind of the

writer it has been richly experimental

with ,language, FORM, SYMBOL, and

MYTH.

The modem has meant a decisive break with tradition in most of its manifestations, and what has been distinctively

worthwhile

in the literature

of

this century has come, in considerable

part, from this modem temper. Merely

to name some of the writers who belong in the modem tradition, although

none of them partake of all of it, is to indicate the vitality, variety, and artistic

success of modem writing: T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, Ernest

Hemingway,

William Faulkner, W. B. Yeats, W. H, Auden, D. H. Lawrence,

James Joyce, Henry Adams, Andre Gide, Marcel Proust, Albert Camus, JeanPaul Sartre, Stephana Mallarme, Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, Eugene _

O'Neill, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Rimbaud. And such a list could be continued for many pages.

[References: Carlos Baker, The EchOing Creen, Romanticism, Modernism,

and the Phenomena of Transference in Poetrij (1984); Carol T. Christ, Vict07'ian

and Modern Poetics (1984); Peter Faulkner, Modernism (1977); Irving Howe,

ed., The Idea of the Modem, in Literature and the Aj·ts (1967); Monroe K.

"Spears, Dionysus and the Citsj- Modernism in Twentieth-Celltlll'Y

Poetrij

(1970).]

Modern:

A term applied to one of the main directions in writing in this

century. For most of its history, "modem;' has-denoted or connoted something

bad. In a general-sense

it means having to do with recent times and the

present day, but we shall deal with it herein

a narrow sense more or less

synonymous

with that of "modernist."

It is not a chronological

designation

but one suggestive of a .loosely defined congeries of characteristics.

Much

twentieth-century

literature

is not "modern" in the common sense of the

term, as much that is contemporary

is not. Modern refers to a group of characteristics, and not all of them appear inanyone

writer who merits the designation moddnl.

In abroad

sense modem is applied to writing marked by a strong and

conscious break with traditional forms and techniques, of expression. It employs

a distinctive kind of IMAGINATION, one that.insists on having its general frame

of reference

within itself. It thus practices the solipsism of which Allen Tate

accused the modern mind: it believes 'that we create the world in the act of

perceiving it. Modem implies a historical discontinuity,

a sense of.alienation,

loss, and despair. It not only rejects history but also rejects the society of

whose fabrication history is a record. It rejects traditional values and assumptions, and it rejects equally the RHETORIC by which they were 'sanctioned

and' communicated.

It elevates the individual and the inner 'being -over the

social human being and prefers the unconscious

to the self-conscious, The

psychologies of Freud and [ung have been seminal in the modern movement

Modernist Period in English Literature:

The Modernist Period in England

may be considered

to begin with the First World War in 1914, to be marked

by the strenuousness

of that experience

and by the Howering of talent and

experiment

that came during the boom of the twenties and that fell away

dunng rhe ordeal of the economic depression in the 1930s. The catastrophic

years of the .Second World War, which made England an embattled

fortress,

profoundly

and negatively

marked everything

British, and it was followed

by a period of desperate

uncertainty,

a sadly dim,inished age. By 1965, which

to all purposes marked an end to the Modemist Period, the uncertainty

was

giving way to anger and protest.

In the early years of the lviodemist Period, the novelists of the Enw Al'tDIAN

AGE continued

as 'major figures, with Galsworthy,

Wells, Bennett,

Forster,

and Conrad dominating

the scene, joined before the 'teens were over by Somerset Maugham. A new FICTION, centered

in the experimental

examination

ofthe inner self, was coming into being in the works of writers like Dorothy

Richardson and Virginia Woolf. It reached its peak in the publication in 1922

of,(James Joyce's Ulysses, a hook perhaps as influential as any PROSE work by

a British writer in this ceritury. In highly differing ways D. H. Lawrence,

Aldous Huxley, and Evelyn Waugh protested

against the nature of modern

society; and the maliCiously witty NOVEL, as Huxley and Waugh wrote it in

the twenties and thirties, was 'typical of the attitude of the age and is probably

f.

Modernist Period in English Literature

~

310

311

as truly representative of the English novel in [he contemporary period as

is the, NOVELexploring the private self through the STREAMOF CONSCIOUSNESS

..

In the thirties and forties. Joyce Cary and Graham Greene produced a more

traditional FICTIONof great effectiveness. and Henry Green made grim comedy

of everyday life. Throughout the period English writers have practiced the

SHORT STORYwith distinction; notable examples being Katherine Mansfield

and Somerset Mangham, working in the tradition of Chekhov.

The theater saw the social PLAYSof Calsworthy, Jones. and Pinero. the

PLAYof ideas of Shaw. and the COMEDYOF MANNERSof Maugham-all

wellestablished in the EDWARDIANAGE-continue and be joined by Noel Coward's

COMEDY.the proletarian DRAMAof Sean O'Casey, the serious VERSE plays

of T. S. Eliot and Christopher Fry. and the high craftsmanship of Terence

Rattigan.

Perhaps the greatest changes in literature. however. came in POETRY

and CRITICISM. In 1914 Bridges was POET LAUREATE;he was succeeded in

1930 by John Masefield, who died in 1967. Wilfred Owen was one of the

most powerful poetic voices of the. early years of the contemporary period.

but his career ended with an untimely death in the First World War. Through

the period Yeats continued poetic creation. steadily modifying his style and

subjects to his late form. At the time of his death in 1939 he probably shared

with T.S. Eliot the distinction of being the most influential POET in the British

Isles. Yet Eliot's The Waste Land. although its author was American. was the

most important single poetic publication in England inthe period. (One striking

feature of The Waste Land is its specificity as to "geography in the "City"

part of London. along with its global scope. which includes even Australia

and the South Pole while omitting-as if deliberately=-virtually

any reference

to the United States.) In the work ofYeats and Eliot. of W.H. Auden, Edith

Sitwell, and Gerard Manley Hopkins. whose POEMSwere posthumously published in 1918. anew POETRY came emphatically into being. The death at

thirty-nine of Dylan Thomas in 1953 silenced a powerful LYRICvoice, which

had already produced fine POETRYarid gave promise of doing even finer work.

T. S. Eliot and I. A. Richards. along with T. E. Hulme. Wyndham Lewis, Herbert

Read, F. R. Leavis, Cyril Connolly, William Empson, and others, created an

informed, .essentially anti-Romantic ANALYTICAL·CRITICISM,centering its attention on the work of art itself.

Between 1914 and 1965, modernism (see MODERN)as a literary mode

developed and gained a powerful ascendancy, and, disparate as many of the

writers and movements of the period were, they seem. in hindsight. to have

shared most of the fundamental assumptions about art, humanity, and life

embraced in the term MODERN.But, however much the literary movement

in the Modern Period seems to have a unified history. Great Britain was during

the time in the process of national and cultural diminution. for England in

the twentieth century has watched her political and military supremacy gradually dissipate, and since the Second World War she has found herself greatly

reduced in the international scene and torn by internal economic and political

troubles. Her writers during these turbulent and unhappy years turned inward

for their subject matter and expressed bitter and often despairing cynicism.

Her major literary figures in the Modernist Period, as they were in the EDWARDIAN AGE, were often non-English. Her chief POETS were Irish, American ..

~

Monostrophic

, and Welsh; her most influential novelists, Polish and Irish; her principal dramatists, Irish and American. See Outline oj Literary History.

Modulation:

In music a change in key in the Course of a passage or between

passages. In POETRY a variation in the metrical pattern by the SUBSTITUTION

of a FOOT that differs from the basic METER of the LINE or by the addition

Or deletion of unstressed syllables. Hardy's "The Voice" may be said to modulate from a largely DACTYLLICrhythm in its Erst three STANZASto a largely

TROCHAICrhythm in the fourth.

Monodrama:

The term monodrama is used in three senses, all related to

its basic meaning of a dramatic situation in which a single person speaks. At

its simplest levela monodrama isa DRAMATICMONOLOGUE.It is more often

applied to a series of extended DRAMATICMONOLOGUESin various METERS

and STANZAFORMSthat tell a connected story. The standard example is Tennyson's Maud, which the poet called a monodrama. The term is also applied

to theatrical.presentations

thatfeature

only one actor.

Monody: A DIR'GEor LAMENTin which a single mourner expresses individual

grief, for example, Arnold's Thsjrsis, A Monody. See DIRGE,ELEGY,THRENODY.

Monograph:

A rather indefinite term for a piece of scholary writing, usually

on a relatively limited topic. Monographs may be published as separate volumes,alone or as part of a series, but their size normally falls between that

of an ARTICLEand that of a full-length book.

Monologue:

A composition, oral or written, presenting the discourse of one

speaker only. By convention, a monologue is a speech that represents what

someone would speak aloud in a situation with listeners, although they do

not speak; the monologue therefore differs somewhat from the SOLILOQUY,

which is a speech that represents what someone is thinking inwardly, without

listeners. Any speech or: NARRATIVEpresented wholly by one person. Sometimes loosely used to signify merely any lengthy speech. See DRAMATICMONO- .

LOGUE,INTERIOR MONOLOGUE,MONODRAMA.

Monometer:

A LINE of VERSEconsisting of one FOOT. See SCANSION,METER.

Monorhyme:

A POEM that uses only one RHYME. Even short examples are

u~common: Browning's "Home-Thoughts, from the Sea "is seven LINES,Frost's

"The Hardship of Accounting" five. Longer examples are rarer yet: Browning's

"Through the Metidja to Abd-el-Kadr" is a forty-line POEM on one RHYME

sound, but, because of a recurring REFRAIN,there are only twenty-six different

rhyme words; Hardy's "The Respectable Burgher," thirty-Bvelines. on one

rhyme sound with thirty-Bve different rhyme words, seems to have established

a record.

Monostich:

A POEM consisting of a single LINE. A recent instance is A. R.

Ammons's "Coward."

Monostrophic:

A term used by Milton to describe the FORMfor the CHORUSES

in Samson Agonistes. These choruses are continuous, each consisting of a single

r-

Virgin Play

~

"tt

524

1 is repeated as lines 6, 12, and 18; line 3 as lines 9, 15, and 19. The first

and third lines. return as a rhymed COUPLE:rat the end. The scheme of RHYMES

(or REPETITIONS)is aha aha aha aha abaa. The villanelle first appeared in

English VERSE in the second half of the nineteenth century, originally for

Fairly lighthearted POEMS. (The earliest American oillanelle 'was written by

James Whitcomb Riley.) The obsessive repetition that can represent 'ecstatic

affection also works for static preoccupation,

as in serious villanelles by

E. A. Robinson and William Empson. The finest villanelle in any language-sand one of the' greatest modern POEMSin any FORM-is Dylan Thomas's "Do

. Not Go Gentle into That Good Night."

Virgin Play: A medieval nonscriptural PLAYbased on SAINTS'LIVES,in which

the Virgin Mary takes an active role in performing miracles. See MIRACLE

PLAY.

Virgule: A slanting or an upright line used in PROSODYto mark off metrical

FEET, as in the following example from Shelley:

Th;

S~ll1

--.;

I is

The waves

I

w~rm,

I

-.;

are dan

th; sk~

--"

I cing

I is

fast

cJ~ar,

I

--

,

and bright

Since the Second World War, the virgule, sponsored by Ezra Pound and

Charles Olson, has joined the fashionable punctuation of POEMS. With the

legalistic "and/or" (unnecessary, since "or" means "and lor"), the virgule has

come to supplant the hyphen.

Voice-Over: In FILM the use of a NARRATOR'Sor commentator's words when

the speaker is not seen by the viewer. The voice-over may be a NARRATIVE

bridge between SCENES,a statement of facts needed by the viewer, or a cornment on the CHARACTERSand ACTIONS in the scene, In special cases the

voice-over may be in the voice of the character represented in the scene

but not a part of the action in the. SCENE. In Olivier's Hamlet, for example,

we hear Olivier in a voice-over speaking the words of SOLILOQUIESwhile

we see his motionless, pensive face on the screen'. Compare with SOUND-OVER.

Volta: The turn in thought-from

question to answer, problem to solutionthat occurs at the beginning of the SESTETin the ITALIANSONNET.The volta

sometimes occurs in the SHAKESPEAREANSONNET between the twelfth and

the thirteenth lines. The volta is routinely marked at the beginning of LINE

9 (Italian) or 13 (Shakespearean) by "but," "yet," or "and yet." The design

of Hardy's "Hap" is perspicuous:

Line}:

Line 5;

Line 9:

"If ... "

"Then..

"

"But not so .

.The distinctive characteristic of the MILTONIC SONNETis the absence of the

volta in a fixed position, although the FORM is Italian in RHYMESCHEME.

Vorticism: Earlier, a term applied to the binomial epistemology of Descartes.

A movement in modern POETRYrelated to the manifestation of certain abstract

525

~

~

~

t

I

i

~

r

l

I

~

~

I

~

~

~

ili

•

'J1I

(

II

~

~

~.'.

J

,I

I~

•

I

•I•

•I

•

•

;I~;.t'

:;i:: i

..

,.

".

~.l

~~{

~

..•...

~t,

tl'.~

;A.'·

II~

.~

.~

I

I

I

~

I

I

~

Vulgate

developments and methods in painting and sculpture. Vorticism originated

in 1914 with Wyndham Lewis's effort to oppose Romantic and vitalist theories

with a kind of verbal and visual art based on SPATIALFORM, clarity, definite

outline, and mechanical dynamism. Ezra Pound used the vorticist idea in

POETRYas an extension of IMAGISM,which seemed constrained to work only

in short works or limited passages and to lack force. In vorticism abstraction

frees the artist or POET from'lt,he IMITATION of NATURE, and the vortex is

energy changed by the poet or artist into FORM, this form being paradoxically

both still and moving. Aside fr~m the work of Pound, vorticism had limited

influence. The practice of vorticism in the graphic arts can best be seen in

Lewis's paintings and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska's sculpture.

[References: Timothy Materer, Vortex: Pound, Eliot, and Lewis (1979);

William C. Wees, Vorticism and the English Avant-Garde (1972).]

Vulgate: The word comes from Latinvulgus, "crowd," and means "common"

or "commonly used." Note two chief uses; (1) the Vulgate BIBLE is the Latin

version made by Saint Jerome in the fourth century and is the authorized

Bible of the Catholic Church; (2) the "Vulgate ROMANCES"are the versions

of various CYCLESof ARTHURIAN romance written in Old French PROSE(common or colloquial speech) in the thirteenth century and were the most Widely

used FORMSof these STORIES,forming the basis of Malory's Le Morte Darthur

and other later treatments. See ARTHURIAN LEGEND.