Document 10709392

advertisement

Postcolonial fiction

Major issues (from Deepika Petraglia-Bahri)

Despite the reservations and debates, research III Postcolonial Studies is growing because

postcolonial critique allows for a wide-ranging investigation into power relations in various

contexts. TIle formation of empire, the impact. of colonization on postcolonial history, e;conomy,

science.jmd culture.rthe cultural productionsofcolonized

societies, femiWsm an~f' . ... ... -,

postcolonialism; agency for·marginalized peopte, and the state of :the p~st~d'ony in'·conten1porary,.

," economic. and culturalcontexts are some broad topics in the field. ~

The following questions suggest soi1'i~'ofth~i1;ajorissues in the field:

How did the experience of colonization affect those who were colonized while also influencing

the cOionizenQ H6\", werecolonial powersable to gaincontrol over 'soIa:rge'a'portloll"ofllle'il0nWestern world? What traces have been Ieftby colonial education, science and .technologyin,

<;1

postcolonial societies? Ho~y.9Q.t;lWWJrft~e~oJ'f'~c;(d.~E.i_~C>l}~

~b()llt.devdopment and,

, modernization in postcolonies? What were the forms of resistance against colonial control? How

did colonial educafionand language influence the culture and identity of the colonized? How did

Western science, technology, and medicine change existing knowledge systemsjWhat are the _

(J

*

eI;~~_~~e.~!.!~~~..,.~fg8?'!S,<?'!~~E~~lj9:~~1WX_.aI!~f~fu,~:"<i.e?a.rtuJ:.e,.of,.1he

...gp19}}!,~el~21:9.~~~~iJi.~

decolRpi~~tIPn.c~ nt.CQlJgruC!Iqnfree :fi:Qlll.c9}oI?J.?-1.iP.fl.u.~.Q.ce)

been possible? Are Western

fonn~lationsoipost~oio};I~llS~'~~~i-emphaslW1g'

~a{ti'1e'ei:pe~~e';f material realities?

Should decolonization proceed through an aggressive return to the pre-colonial past (related

topic: Essentialism)? I:I:?<:;:.99c~~~~~E~I-~~~~.~?

..~!~~~,~,~!.~£1~,,~.S9!9w'~LAAs!R2§tggJpmfl..L~

discourse? Are new forms of imperialism replacing colonization and how?

.

hybhdItY

7'.:.ii!:':.:~'~'i,;.

. .~!:

.f.:.•..~_-:;:n.:~.,:;~C!.-:!..·.;:1C:".~7.:-::;~_-~,...~~~

.. "'.::-:.",:~","••••,::",-

~J"'.' ••

- '.; •• -.'<"'--'

••.,.. •..,."' •• .J;;"

•• ,-~".~,

:.~.e.." .T•.

~.w,,:~~,:·:;;.."t

.,''''0.:::-'':.''''./:.".,-

.;:.

J::>

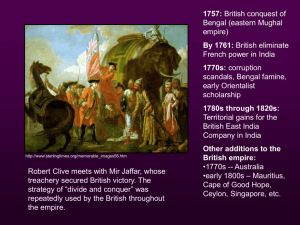

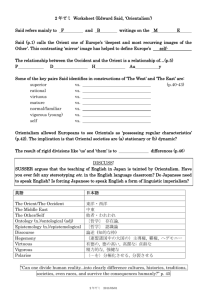

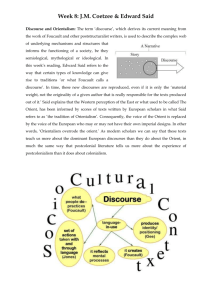

"Orientalism" (in our discussions, it is a negative term as in the views of Edward Said, denoting

a western-constructed view of Asia and the Middle East) (the following is from Danielle Sered).

One of the most significant constructions of Orientalist scholars is that of the Orient itself What

is considered the Orient is a vast region, one that spreads across a myriad of cultures and

countries. It includes most of Asia as well as the Middle East. The depiction of this single 'Orient'

which can be studied as a cohesive whole is one of the most powerful accomplishments of

Orientalist scholars. It essentializes an image of a prototypical Oriental=a biological inferior that

is culturally backward, peculiar, and unchanging=to be depicted in dominating and sexual terms.

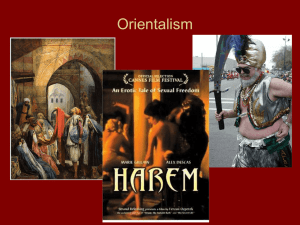

The discourse and visual imagery of Orientalism is laced with notions of power and superiority,

formulated initially to facilitate a colonizing mission on the part of the West and perpetuated

through a wide variety of discourses and policies. The language is critical to the construction. The

feminine and weak Orient awaits the dominance of the West; it is a defenseless and unintelligent

whole that exists for, and in terms of, its Western counterpart. The importance of such a

construction is that it creates a single subject matter where none existed, a compilation of

previously unspoken notions of the Other. Since the notion of the Orient is created by the

Orientalist, it exists solely for him or her. Its identity is defined by the scholar who gives it life.

Said a.rgues that"O'nentailSIn"e~l~f<?~~.W ..PFlt=im,Yi~§~Hr!t.q~Ri-~t.i2R.?.9f:'t¥.:~P.~cH~!u.;~.e.g,:".The

depictionsof "the Arab '''-as irrational, l11en<lciI;Jg",Wltr;u.,.sDyqr:tlJ.Y,.?11.t.i:;:)Yi::stem,

dishonest, and-perhaps ·l~~OSt

importantl

rototypical, ~~e'ideas .iutowhich ,ciri~~~li;t~~hQi~~:~4ipJi~§~:~Y9rY.~~~

These notions .are.trusted .a~~~illldaiions for 1:iRQ1..~cieol

ogies .and poJjcj~.s,,~,~Y~l:9.P~§J?x.£fi

...""."~~

Occident. Said writes: "TIle hold these instruments have. on :tl~elllin_g)s,increCisedby the

.

lllst"itutions built around thenrFoi evef)'Orientallst,quii~lite;aIiy;there-ls

a's;'{ppori's);tem of

staggering power, considering the ephemerality of the myths that Qrientalism propagates.The

~ystem now culminates into the very institutions of the state. To write' aboutthe' Arab Oriental

y~~p

world, therefore, is to write with the authority of a nation, and not with the affirmation of a

strident ideology but with the unquestioning certainty of absolute truth backed by absolute force. "

He continues, "One would find this kind of procedure less objectionabJe as political propaganda-which is what it is, of course--were it Dot accompanied by sermons on the objectivity, the

faimess, the impartiality of a real. historian, the implication always being that Muslims and Arabs

cannot be objective but that Orientalists ... writing about Muslims are, by definition, by training,

by the mere fact of their Westernness. This is the culmination of Orientalism as a dogma that not

only degrades its subject matter but also blinds its practitioners."

Said calls into question the underlying assumptions that fOID1the foundation of Orientalist

thinking. A rejection of Orientalism entails a rejection of biological generalizations, cultural

constructions, and racial and religious prejudices. It is a rejection of greed as a primary

motivating factor in intellectual pursuit. It is an erasure of the line between 'the West' and 'the

Other.' Said argues forthe use of "narrative" rather than "vision" in interpreting the geographical

landscape known as the Orient, meaning that a historian and a scholar would turn not to a

panoramic view of half of the globe, but rather to a focused and complex type of history that

allows space for the dynamic variety of human experience. Rejection of Orientalist thinking does

not entail a denial of the differences between 'the West' and 'the Orient,' but rather an evaluation

of such differences in a more critical and objective fashion. 'TIle Orient' cannotbe studied in a

non-Orientalist manner; rather, the scholar is obliged to study more focused and smaller culturally

consistent regions. The person who has until now been known as 'the Oriental' must be given a

voice. Scholarship from afar and second-hand representation must take a back seat to narrative

and self-representation on the part of the 'Oriental.'

Postcolonial novel (from James Murphy)

The novel has been the aesthetic object of choice for a majority of postcolonial scholars. While

postcolonial writers have by no means failed to produce poetry nor have critics in the field

entirely neglected verse, it is the novel and studies of the novel that have had the greatest

influence in the field. To some degree, this focus on the novel reflects a general shift of attention

.yvitlDnliterary studies away from poetD/"to~vaid:S'naiiailve;but\ve" caii·fliftliefatlil.b:Llt~i1l~·ilo\~ef's

Pi~~~,;J1U.IlanCelll

postcolonial studies to.three fac;!9.I§::~~..

heteroglossic structure,and the function ofthechronotope in the noveI.·

-

~~£r~~S!lfu1i.:~~~C~~~i~:~f·ih~~9~iiJi[·

-",;;.::.: ..j'

.

.

-.

.

..

,."

."_.

__

._ •.•

:.:.,._

.....

,j ••••

,•.••• ."

The representational power of the novel, its ability to give voice to a people in the assertion of

their identity and their history, is of primary importance to postcolonial ",'Titers and scholars.

Poetry, of course, can also serve this purpose, but it is the novel, typically understood as

communal and public (and seen as more accessible to Western readers than poetry which is often

perceived as culturally and locally specific), that in the work of creating its own world, inevitably

recreates and reflects the world out of which it comes. A critic might look at the way a novel both

contributes to and comes outofa narrative of nationhood (or how it does or doesn't operate) in

the context of decolonization and resistance efforts. Postcolonial scholars do not limit this interest

in representation and identity solely to the novels of postcolonial nations. Edward Said has

written on the novels of empire, examining the way they represent the relationship between

empireand colony.

Essential to this exploration of the novel as a representational form is an interrogation of the

whole question of representation.

Essentialism

(from Brian Cliff)

In a specifically postcolonialcontext, we find essentialism in the reduction oftheindigenous

people to an "essential" idea of what it means to be Africanllndian/Arabic, thus simplifying the

task of colonization. Nationalist and liberationist movements often "write back" and reduce the

colonizers to an essence, simultaneously defining themselves in terms of an authentic essence

which may deny or invert the values of the ascribed characteristics (see discussions on reclaiming

the term "Third World," particularly in Chandra Mohanty's "Introduction" to TIllrd World

Women and the Politics ofFenllnism, ed. Chandra Mohanty, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres

[1991] 1-47). Edward Said argues against this inversion, suggesting that "in Post-colonial

national states, the liabilities of such essences asthe Celtic spirit, negritude, or Islam are clear:

they have much to do not only with the native manipulators, who also use them to cover up

contemporary faults, corruptions, tyrannies, but also with the embattled imperial contexts out of

which they came and in which they were felt to be necessary" (Culture and Imperialism [1994]

16).

Salman Rushdie describes essentialism as "the respectable child of old-fashioned exoticism. It

demands that sources, forms, style, language and symbol all derive from a supposedly

homogeneous and unbroken tradition. Or else" ("'Commonwealth Literature Does Not Exist,"

Imaginary Homelands: Essavs and Criticism 1981-199+ [1991] 67). Wole Soyinka strikes a

similar note in Ius analysis of the potential pitfalls of an essentialist movement such as Negritude,

which "stayed within a pre-set system of Eurocentric intellectual analysis of both man and his

society, and tried to re-define the African and his society in those externalized terms" (Mm

Literature and the African World [1976]129, 136).

Representation

(from the Oxford English Dictionary].

1. Presence, bearing, air; Appearance; impression on the sight. 2. An Image, likeness, or

reproduction in some manner of a thing; A material image or figure; a reproduction in some

material or tangible form; in later use, a drawing or painting. (of a person or thing); The action or

fact of exhibiting in some visible image or fOn11;TIle fact of expressing or denoting by means of a

figure or symbol; symbolic action or exhibition. 3. The exhibition of character and action upon

the stage; the performance of a play; Acting, simulation, pretense. 4. The action of placing a fact,

etc., before another or others by means of discourse; a statement or account, esp. one intended to

convey a particular view or impression of a matter in order to influence opinion or action. 5. A

formal and serious statement of facts, reasons, or arguments, made with a view to effecting some

change, preventing some action, etc.; hence, a remonstrance, protest, expostulation. 6. The action

of presenting to the mind or imagination; an image thus presented; a clearly conceived idea or

concept; TIle operation of the mind in forming a clear image or concept; the faculty of doing this.

7. The fact of standing for, or in place of, some other thing or person, esp. with a.right or

authority to act on tIleir account; substitution of one thing or person for another. 8. The fact of

representing orbeing represented in a legislative or deliberative assembly, spec. in Parliament;

. the position, principle, or system implied by this; The aggregate of those who thus represent the

. elective body.

Representations (from AIm Marie Baldonado )-- these 'likenesses'--come in various forms:

films, television, photographs, paintings, advertisements and other forms of popular culture.

Written materials+academic texts, novels and other literature, journalistic pieces+are also

important forms of representation. These representations, to different degrees, are thought to be

somewhat realistic, or to go back to the definitions, they are thought be 'clear' or state 'a fact'. Yet

how can simulations or "impressions on the sight" be completely true? Edward Said, in his

analysis of textual representations of the Orient in Orientalism, emphasizes the fact that

representations can never be exactly realistic:

.

In any instance of at least written language, there is no such thing as a delivered presence, but a

. re-presence, or a representation. TIle value; efficacy, strength, apparent veracity of a written

statement about the Orient therefore relies very little, and cannot instrumentally depend, on the

Orient as such. On the contrary, the written statement is a presence to the reader by virtue of its

having excluded, displaced, made supererogatory any such real thing as "the Orient". (21)

Representations, then can never really be 'natural' depictions of the orient. Instead, they are

constructed images, images that need to

interrogated for their ideological content.

be

Development

of post-colonial literatures

Post-colonial literatures developed through several stages which can be seen to

correspond to stages both of national or regional consciousness and of the project of

asserting difference from the imperial centre. During the imperial period writing in the

language of the imperial centre is inevitably, of course, produced by a literate elite whose

primary identification is with the colonizing power. Thus the first texts produced in the

colonies in the new language are frequently produced by 'representatives' of the imperial

power; for example, gentrified setlers (Wentworth's 'Australia'), travellers and sightseers

(Froude's Oceana, and his The English.in the West Indies, or the travel diaries of Mary

Kingsley), or the Anglo-Indian and West African administrators, soldiers, and

'boxwallahs', and, even more frequently, their memsahibs (volumes of memoirs).

Such texts can never form the basis for an indigenous culture nor can they be integrated

in any way with the culture which already exists in the countries invaded. Despite their

detailed reportage of landscape, custom, and language, they inevitably privilege the

centre, emphasizing the 'home' over the 'native', the 'metropolitan' over the 'provincial' or

'colonial', and so forth. At a deeper level their claim to objectivity simply serves to hide

the imperial discourse within which they are created. That this is true of even the

consciously literary works which emerge from this moment can-be illustrated by the

poems and stories of Rudyard Kipling. For example, in the well-known poem 'Christmas

in India' the evocative description of a Christmas day in the heat ofIndia is

contextualized by invoking its absent English counterpart. Apparently it is only through

this absent and enabling signifier that the Indian daily reality can acquire legitimacy as a

subject of literary discourse.

..

The second stage of production within the evolving discourse of the post-colonial is the

literature produced 'under imperial licence' by 'natives' or 'outcasts', for instance the large

body of poetry and prose produced in the nineteenth century by the English educated

Indian upper class, or African 'missionary literature' (e.g. Thomas Mofolo's Chaka). The

producers signify by the very fact of writing in the language of the dominant culture that

they have temporarily or permanently entered a specific .and privileged class endowed

with the language, education, and leisure necessary to produce such works. The

Australian novel Ralph Rashleigh, now known to have been written by the convict

James Tucker, is a case in point. Tucker, an educated man, wrote Rashleigh as a 'special'

(a privileged convict) whilst working at the penal settlement at Port Macquarie as

storekeeper to the superintendent. Written on government paper with government ink and

pens, the novel was clearly produced with the aid and support of the superintendent.

Tucker had momentarily gained access to the privilege of literature. Significantly, the

moment of privilege did not last and he died in poverty at the age of fifty-eight at

Liverpool asylum in Sydney.

It is characteristic of these early post-colonial texts that the potential far subversion in

their themes cannot be fully realized. Although they deal with such powerful material as

the brutality of the convict system (Tucker's Rashleigh), the historical potency of the

supplanted and denigrated native cultures (Mofolo's Chaka), or the existence of a rich

cultural heritage older and more extensive than that of Europe (any of many nineteenthcentury Indo-Anglian poets, such as Ram Sharma) they are prevented from fully

exploring their anti-imperial potential. Both the available discourse and the material .

conditions of production for literature in these early post-colonial societies restrain this

. possibility. The institution of 'Literature' in the colony is under the direct control of the

imperial ruling class who alone license the acceptable form and permit the publication

and distribution of the resulting work. So, texts of this kind come into being within the

constraints of a discourse and the institutional practice of a patronage system which limits

and undercuts their assertion of a different perspective. The development of independent

literatures depended upon the abrogation ofthis constraining power and the appropriation

of language and writing for new and distinctive usages. Such an appropriation is clearly

the most significant feature in the emergence of modern post-colonial literatures ...

© 1989 Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. Reprinted from Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths,

and Helen Tiffin, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures (London

and New York: Routledge, ]989) .

.

[From Said, Edward. Orientalism, New York: Vintage, 1979.]

Unlike the Americans, the French and British--less so the Germans, Russians, Spanish,

Portugese, Italians, and Swiss--have had a long tradition of what I shall be calling

Orientalism, a way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orient's

special place in European Western Experience. The Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; .

it is also the place of Europe's greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its

civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most

recurring images of the Other. In addition, the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the

West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience. Yet none of this Orient is

merely imaginative. The Orient is an integral part of European material civilization and

culture. Orientalism expresses and represents that part culturally and even ideologically

as a a mode of discourse with supporting institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, imagery,

doctrines, even colonial bureaucracies and colonial styles ....

It will be clear to the reader. ..that by Orientalism I mean several things, all of them, in my

opinion, interdependent. The most readily accepted designation for Orientalism is an

academic one, and indeed the label still·serves in a number of academic institutions.

Anyone who teaches, writes about, or researches the Orient--and this applies whether the

persion is an anthropologist, sociologist, historian, or philologist--either in its specific or

its general aspects, is an Orientalist, and what he or she says or does is Orientalism ....

Related to this academic tradition, whose fortunes, transmigrations, specializations, and

transmissions are in part the subject of this study, is a more general meaning for

Orientalism. Orientalism is a style of thought based upon ontological and epistemological

distinction made between "the Orient" and (most of the time) "the Occident." Thus a very

large mass of writers, among who are poet, novelists, philosophers, political theorists,

economists, and imperial administrators, have accepted the basic distinction between East

"

and West as the starting point for elaborate accounts concerning the Orient, its people,

customs, "mind," destiny, and so on .... the phenomenon of Orientalism as I study it here

deals principally, not with a correspondence between Orientalism and Orient, but with the

internal consistency of Orientalism and its ideas about the Orient .. despite or beyond

any corrsespondence, or lack thereof, with a "real" Orient. (1-3,5)

![Orientalism PPT[1].](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009508903_1-bf40dd03912d19b9c9baea1f12c90f25-300x300.png)