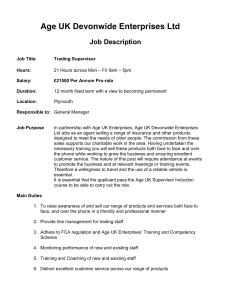

Document 10709315

advertisement