Management and economic analysis of ... strengthening and rehabilitation of reinforced ...

advertisement

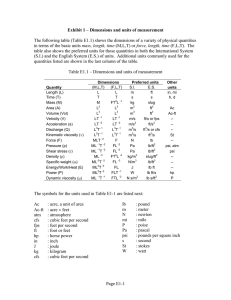

Management and economic analysis of an experimental study for strengthening and rehabilitation of reinforced concrete frame with CFRP F. Rangelova Department of Construction Management and Economics, University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy (UACG), Sofia, Bulgaria, fantina_fce@uacg.bg E. Abdulahad Department of Solid Structures, University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy (UACG), Sofia, Bulgaria, georgosing@gmail.com D. Panichkov Department of Solid Structures, University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy (UACG), Sofia, Bulgaria ABSTRACT: The Bulgarian building heritage’s evaluation showed that large percent of the buildings needed to be rehabilitated. Thereby, the development of effective and affordable rehabilitation techniques is an urgent need. The Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) composites can provide rehabilitation alternative for unreinforced masonry walls. In addition to their outstanding mechanical properties, the advantages of the FRP composites versus conventional materials for rehabilitation and strengthening of structural elements include: unchanged dynamic properties of the structures because little addition of weight and stiffness, lower installation cost, improved corrosion resistance, onsite flexibility of use, minimum changes in the member size after repair, minimized disturbance to the structures’ occupants, minimized loss of usable space during the rehabilitation. The main objectives of the presented and analyzed experimental study is to be develop an advanced method for strengthening and rehabilitation of reinforced concrete frame with CFRP Composites, standing new and pendant research topic and activities for Bulgaria. 1 INTRODUCTION The Bulgarian building heritage’s evaluation showed that large percent of the buildings needed to be rehabilitated. Thereby, the development of effective and affordable rehabilitation techniques is an urgent need. The strengthening of concrete structures with externally bonded steel reinforcement is already a wellknown technique for many years. The basic principle of externally bonded reinforcement is very simple. Additional reinforcement, in most cases for carrying tensile forces, is added to the structure by bonding it onto the structure’s elements. Originally only steel plates were used, but with the development of new high grade FRP (fibre reinforced polymers) materials (e.g. in the aerospace industry), new materials became available to be used for structural strengthening purposes. In management of civil engineering structures, lack of decision support tools, which identify the whole of life benefit/cost of using smart materials and technologies such as Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) composites, hinders adoption of such smart technologies. A newly commenced research project the Bulgarian CRC for Construction Innovation was primarily being undertaken at Structural Laboratory at the UACG is aimed at addressing this gap in knowledge by developing an integrated framework for the use of FRP composites in rehabilitation of civil engineering reinforced concrete and masonry structures. Fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) is a composite material made by combining two or more materials to give a new combination of properties. However, FRP is different from other composites in that its constituent materials are different at the molecular level and are mechanically separable. The mechanical and physical properties of FRP are controlled by its constituent properties and by structural configurations at micro level. Therefore, the design and analysis of any FRP structural member requires a good knowledge of the material properties, which are dependent on the manufacturing process and the properties of constituent materials. FRP composite is a two phased material, hence its anisotropic properties. It is composed of fiber and matrix, which are bonded at interface. Each of these different phases has to perform its required function based on mechanical properties, so that the composite system performs satisfactorily as a whole. In this case, the reinforcing fiber provides FRP composite with strength and stiffness, while the matrix gives rigidity and environmental protection. In addition to their outstanding mechanical properties, the advantages of the FRP composites versus conventional materials for rehabilitation and strengthening of structural elements include: unchanged dynamic properties of the structures because little addition of weight and stiffness, lower installation cost, improved corrosion resistance, onsite flexibility of use, minimum changes in the member size after repair, minimized disturbance to the structures’ occupants, minimized loss of usable space during the rehabilitation. Different fibre types can be used, but most commonly carbon, glass or aramid are applied The corresponding composites are indicated as CFRP, GFRP or AFRP. The good mechanical properties of the FRP materials are only available in the fibre direction. Mainly, two types of FRP reinforcement are available on the market: hardened plates and flexible sheets (wet lay up). The end result, the fibres embedded in a resin matrix is often indicated by the term “laminate”. In the early stage, the hardened FRP plates were autoclaved, which limited the available length. Later on, FRP plates produced without autoclaving came on the market. These plates are available in different thicknesses, widths and stiffness and with nearly unlimited length. The application of these hardened FRP plates is analogous to the application of steel plates. Another type of FRP reinforcement is the UD-sheets, which are very flexible and can easily be cut by means of scissors, figure 1. At application, the flexible sheets are impregnated with the right ratio of epoxy resin components and the chemical reaction starts. When the first layer has hardened enough, the second layer can be applied in the same manner. The sheets are completely impregnated on the site. Both types of FRP, the sheets and the plates, are available on roll, which means that they are available in any length, whereas the steel plate length is limited in practice to 6 meters. The FRP materials consist of continuous fibres embedded within a thermosetting resin system. The resin is required to bond the fibres together and transmit loads between fibres. Some mechanical properties such as in-plane and interlaminar shear are highly resin dependent, whilst others such as longitudinal strength and stiffness are highly fibre dependent. The most common resins used in FRP are polyester based, which are economical and of low-moderate strength. Numerous grades of polyester resin are available, but the most common consist of either orthophthalic or isophthalic saturated acids. Orthophthalic resins are more economical but exhibit low mechanical properties and chemical resistance and are less likely to be suitable for the reinforcement of concrete structures, where good resistance to alkaline environments and low shrinkage may be required. Vinylester and epoxy based resins offer improved mechanical properties but with increased cost. However, if high performance fibres such as aramid or carbon are being used, the resin will only form a very small portion of the total cost. This is another reason why for structural purposes nearly always an epoxy resin will be used. Carbon fiber is higher-performance fiber available for civil engineering application. They are manufactured by controlled pyrolysis and crystallization of organic precursors at temperatures above 2000 oc. In this process, carbon crystallites are produced and orientated along the fiber length. There are three choices of precursor used in manufacturing process of carbon fibers-rayon precursors, polyacrylonitrile (PAN) precursors, and pitch precursor. PAN precursors are the major precursors for commercial carbon fibers. It yields about 50% of original fiber mass. Pitch precursors also have high carbon yield at lower cost. However, they have less uniformity of manufactured carbon fibers. Carbon fibers have high elastic modulus and fatigue strength than those of glass fibers. Considering service life, studies suggests that carbon fiber reinforced polymers have more potential than aramid and glass fibers. The main objectives of the presented and analyzed experimental study is to be develop an advanced method for strengthening and rehabilitation of reinforced concrete frame with CFRP Composites, standing new and pendant research topic and activities for Bulgaria. Regardless of the well known advantages of FRP one critical issue need to be justified. The important issue that must be determined is the competitiveness of FRP strengthening method on a cost basis in the future, compare to conventional methods such as strengthening with steel. Life Cycle Cost is probably the best process to answer that issue. Life Cycle Cost of FRP strengthening method includes the Initial Costs, Maintenance/Inspection/Repair Costs, and Disposal Costs. The use of FRP composites as a strengthening solution for reinforced concrete frame is expected to increase service life and lower maintenance costs. The main problem encountered is the initial costs of FRP strengthening method are significantly higher than those from steel. Hence, the initial costs of FRP strengthening must be reduced to be cost competitive with the steel on a life cycle cost basis. The initial future costs can be estimated by utilizing improvement (learning) curve theory and various improvement models to predict future costs are under development. The various models apply the improvement theory with different bases and the results obtained are varied. The preliminary results indicate that CFRP strengthening method become economically feasible. 2 EXPERIMENTAL SET UP For the goals of the experiment there were prepared two reinforced concrete beams, particularly connected with two columns (frames). The beams is reinforced with 2N10 bottom reinforcement and 2N10 top reinforcement, and stirrups Ø6,5 by 20 cm. The columns are reinforced with 4N14 and stirrups Ø6,5 by 20 cm. Between the columns and beams are implemented a masonry for realization of the real task of the experimental study. The shoulder with columns and beam masonry is loaded with horizontal and vertical force. After frames’ collapse they were strengthened: one of them with CFRP system, and one with shaped steel and steel plates and tires: Figure 1. Reinforced Concrete Frame strengthened with CFRP 200 20 2 1 2 175 25 1 1-1 2-2 25 шини-5mm L 50/50/5 25 Figure 2. Reinforced Concrete Frame strengthened with Steel Figure 3. Reinforced Concrete Frame strengthened with CFRP In the experimental work the follow FRP materials and systems were applied: MEGAWRAP 200 – one directional carbon fibers laminate with follow technical characteristics: - carbon fibers’ weight – 200 g/m2 ; - total carbon fibers’ weight - 224 g/ m2 ; - thickness – 0,11 mm; - tension strength ffib - 3800 MPa ; - module of elasticity Efib - 235 GPa; - deformation by breakdown εfib - 1,5%; - density 1,81 g/m3. The mechanical properties of the carbon fibers are average quantities, received experimentally by tests for tension strength by ASTMD 4018-81 EPOMAX – LD Two-component epoxy resin is appropriate for carbon and synthetic fibers, which are used for static strengthening or reinforced concrete elements’ correction: - flexural strength – 44,6 MPa; - elastic extension – 1,7 %; - Stress strength – 90 MPa; - Tension strength – 70 MPa; - Module of elasticity – 2500 MPa; - Adhesion strength - >4 N/mm2. The experiment was implemented in the Structural Laboratory to the Department of Solid Structures at the University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy (UACG), Sofia, Bulgaria with assistance of “ISOMAT INTERNATIONAL” Ltd. and “A&K Engineering” Ltd. The CFRP strengthening was performed with application of 2,5 м2 carbon fiber laminate with thickness t = 0,11mm, and with 2,5 kg epoxy resin (1kg/m2). The steel strengthening was performed with application of 35 numbers tires with dimensions: 150/50/5 mm, 11 m shaped steel - L50/50/5, edge-iron plates with А = 900см2, d = 5mm and 108 dubels - 50/5 mm. There was implementing and about 3 m2 guniting with thickness 2 cm. learning curves have been applied to all types of work from simple tasks to complex jobs. Improvement curves are a more appropriate name for learning curves. Improvement rate is the complement of learning rate; thus if the learning rate is 90 percent, the improvement is 10 percent. The implemented experimental investigations give the reason to be assumed that the strengthening with the CFRP’s is effective. It means that the character of the work of the reinforced concrete elements is the same. Only the bearing capacity of the reinforced concrete elements increasing, and guarantee rehabilitation of a part of the constructive physical wear. 3 COST ANALYSIS There are two approaches one could use for cost analysis, initial costs and life cycle costs. Basically, initial costs are a subset of life cycle cost. When initial cost is the major cost component, life cycle costing results will be similar to considering only initial costs. However, when inspection, maintenance, and disposal costs become dominant, life cycle costing should be utilized. 3.1 Initial coast Initial costs include the material cost, component manufacturing, fabrication, assembly, shipment, installation and testing costs. They reflect the largest costs in most strengthening methods and are appropriate for a majority of the applications. When comparing conventional and composite strengthening methods on the basis of initial costs, it’s clear that the direct initial costs favor conventional one. The higher initial cost of CFRP strengthening method is expected due to the high fiber and resins costs. However, the maintenance, rehabilitation, demolition, and indirect costs favor composite strengthening. Projects with long lives require that life cycle costing be utilized, as polymer strengthening should have reduced rehabilitation and maintenance costs. In order to be competitive, it is felt that the initial costs of CFRP strengthening must be approximately € 40 per square meter to be competitive with steel strengthening solution. 3.1.1 Improvement Curves Learning curve was first applied in the aircraft industry, and translated into an empirical theory in 1925. In 1936 T. P. Wright disclosed the results of empirical tests of the learning curve and described a basic theory for obtaining cost estimates based on repetitive production of airplane assemblies. Since then, Figure 4. Typical Learning Curve (Xanthakos, 1995) 3.2 Life Cycle Costs Whole of Life cycle cost analysis (WLCCA) is an evaluation method, which uses an economic analysis technique that allows comparison of investment alternatives having different cost streams. WLCCA evaluates each alternative by estimating the costs and timing of the cost over a selected analysis period and converting these costs to economically comparable values considering time-value of money over predicted whole of life cycle. The analysis results can be presented in several different ways, but the most commonly used indicator in construction asset management is net present value of the investment option. The net present value of an investment alternative is equal to the sum of all costs and benefits associated with the alternatives discounted to today’s values (Darter and Smith, 2003). Making a decision for selection of the rehabilitation method will be done by minimizing the life cycle costs. Such a decision analysis is referred as a whole of life cycle costing, cost-benefit or cost-benefit-risk analysis. Life cycle costs will assess the cost effectiveness of design decisions, quality of construction or inspection, maintenance and repair strategies (Stewart, 2001). Life Cycle Costing (LCC) is defined as "The total cost of the system or product under study over its complete life cycle or the duration of the period of study, whichever is the shorter". The study period of LCC is defined as the length of time over which an investment is evaluated. It depends on time horizon of investor or expected life of system. Three key dates of study period are base date (beginning of study period), service date (beginning of operational period), and end date (end of study period). The six main steps in an LCC analysis are: (1) Identify feasible project alternatives (2) Establish common assumptions (3) Identify relevant project costs (4) Convert all money amounts to present value (5) Compute and compare LCCs of alternatives, and (6) Interpret results. In order to get appropriate analysis, assumptions should be clearly defined; the most common ones are the definition of Life, Costs, Initial costs, Discounting and Inflation, Taxation, and Benefits. Since FRP is a new-technology material, it is required to compare this technology with the conventional technologies. Ehlen and Marshall recommend the following steps for calculating the life cycle cost of a new-technology material vis-à-vis a conventional material. Those steps are: o Define the project objective and minimum performance requirements; o Identify the alternatives for achieving the objectives; o Establish the basic assumptions for the analysis; o Identify, estimate, and determine the timing of all relevant costs; o Compute the LCC for each alternative; o Perform sensitivity analysis by re-computing the LCC for each alternative using different assumptions; o Compare the alternative’s LCCs for each set of assumptions; o Consider the other project effects; o Select the best alternative. In each alternative the user should use the same fixed discount rate and the same study period. Implicit in any LCC analysis is the assumption that every proposed alternative will satisfy the minimum performance requirements of the project. These requirements include structural, safety, reliability, environmental and specific building code requirements. The Perform sensitivity analysis by recomputing the LCC for each alternative using different assumption is the life cycle cost method is a fundamental part of assessing new construction material. The costs and technical performance of new materials are intrinsically uncertain; and this method must address this uncertainty. The inherent cost uncertainty of materials and designs that are not in mainstream use can be handled with Monte Carlo simulation. Further, those researchers suggested using the LCC classification scheme when evaluating newtechnology material, mainly to make sure that all costs associated with the project are taken into account in each alternative. Three level cost classification proposed include: Level 1: Costs by LCC Category (typically used are construction, operation/ maintenance/ repair, and disposal); Level 2: Costs by the Entity that Bears the Cost (agency costs, user costs, and third-party costs), and Level 3: Costs by Elemental Breakdown (elemental costs, nonelemental costs, new-technology introduction costs). The life cycle cost of an alternative is represented by either: (1) Present Worth Cost or (2) Equivalent Uniform Annual Cost. Another approach might be used is Benefit/Cost Ratio. The equation to calculate the life-cycle cost of an alternative using the first approach is as follows: LCC (PV) = PVIC + PVOMR + PVD PVIC = Present Value of Initial Costs PVOMR = Present Value of Operation, Maintenance, and Repair costs PVD = Present Value of Disposal costs The costs associated in a rehabilitation project may initially include: o Initial cost; o Maintenance, monitoring and repair cost; o Extra user cost; o Estimated cost of failure All of these costs are valued in resource cost terms (i.e. Market prices + subsidies - taxes). If monitoring, repair, extra user cost are considered as the maintenance cost. Benefit Cost Ratio method in principle examines the extra benefits of advancing one improvement level to the next divided by the corresponding extra costs. Cost-Benefit Comparison is suitable for comparing alternatives with equivalent life expectancy, performance and maintenance. If significant differences are expected in one of these factors, first cost analysis will not give a true comparison of cost effectiveness of the various alternatives. Life cycle cost analysis is similar to first cost analysis except that future costs are also considered. Typically, future costs include maintenance, future rehabilitation expenditures, and probable replacement costs. In life cycle cost analysis, future costs must be discounted to present worth before they are combined with present (immediate) costs. 3.3 Initial Cost Feasibility Study When evaluating first-cost in relation to traditional methods, strengthened CFRP technology can be more expensive, but the key advantages of FRP strengthening are often overlooked in relation to their high material and manufacturing costs. FRP strengthening can be cost-effective in the long run. A direct comparison of the unit price basis may not be appropriate, but rather an overall project and lifecycle cost. There are arguments that initial costs of new technologies decrease with time, as their use become more extensive and accepted. On the analogy of Xanthakos (1995), the strengthening method that use FRP are expected to have higher initial costs than traditional strengthened reinforced concrete frame, due to high cost of fiber and resins. However, this initial cost will decrease as more frames are repaired according to the Learning Curve theory. “The Learning Curve theory predicts that, as experience builds up, the cost will decrease in an exponential manner. Typical costs start high, but drop steeply when methods and materials become more cost effective as the product matures. Over time, the large inefficiencies are removed from the process and the costs stabilize.” The economic analysis of presented experimental study show that the reinforced concrete frame’s strengthening with conventional steel is cost about €35, 48 per square meter, compared to the reinforced concrete frame’s strengthening with advanced CFRP composite system, which is cost about € 48,35 per square meter (Table 1.) detour costs and inconveniences. Also, FRP material installation is quite simple; the material is light and can be installed using hand tools. There is a high likelihood that, once trained, the technology can be applied by state employees. Though gains in structural strength may not be a concern for rehabilitation, construction strengthened using the FRP method will experience increases in strength and therefore have higher capacities. Since the costs of the FRP strengthening solution included contracting fees (profit, overhead, etc.), the application of the FRP may become significantly less expensive once this strengthening is performed exclusively by state “inhouse” forces. Repairs using this method are easier and faster to implement. Also, these strengthening tend to be more durable than those using conventional methods, allowing for less frequent re-repairs. Table 1. Initial cost of applied strengthening methods ______________________________________________ Materials/ Steel Method _____________ CFRP System ____________ Work BG Lev Euro BG Lev Euro ______________________________________________ Shaped steel 62,37 33,88 Steel plates 14,76 9,47 Steel tires 9,98 5,10 Dubles 54,00 27,61 Labor 32,40 16,57 36,00 18,41 CFRP 175,00 89,47 Epoxy resin 25,43 13,00 TOTAL 173,51 88,71 236,43 120,88 _____________________________________________ 5 ADVANTAGES OF FRP LAMINATES COMPARED TO CONVENTIONAL MATERIALS 4 ANALYSIS AND CONCLUTIONS The implemented experimental investigations give the reason to be assumed that the strengthening with the CFRP’s is effective. It means that the character of the work of the reinforced concrete elements is the same. Only the bearing capacity of the reinforced concrete elements increasing, and guarantee rehabilitation of a part of the constructive physical wear. Economics analysis shown that the cost of CFRP strengthening method is competitive with the cost of the traditional method, and when “life-cycle” strengthening is included, the FRP method is less expensive. Also, it is likely that once the FRP strengthening solution becomes more widely accepted and used, both material cost and experience in installation will improve (Learning Curve theory). Setting aside cost differentials, the FRP strengthening method has many other advantages over the conventional strengthening method. The most pronounced advantage is speed of application. The FRP method may allow for the construction to remain in exploitation during strengthening. Also, the installation and curing time for the FRP strengthening solution is quite short in comparison to the more complex forming traditional strengthening with steel. Thus the rapid application of FRP repair can lead to reductions in The actual advantages of FRP laminated composites to conventional materials should be estimated from both technical and economic points of view. From technical point of view, composite materials have significant advantages: o Laminated composites offer significant weight saving over existing metals. Composites can provide structures that are 25-45 % lighter than the conventional structures designed to meet the same functional requirements; o Unidirectional fiber composites have specific tensile strength (ratio of material strength to density) about 4 to 6 times greater than that of steel and aluminum; o Unidirectional fiber composites have specific modulus (ratio of material stiffness to density) about 3 to 5 times greater than that of steel and aluminum; o Fatigue endurance limit of composites may approach 60% of their ultimate tensile strength. For steel and aluminum, this value is considerably lower; o Corrosion resistance of fiber composites leads to reduced life cycle cost. From an economic point of view, the main factors contributing to their competitiveness with respect to conventional materials are time saving, flexibility, low labor costs, low tooling and machinery costs on the construction site because of the light weight and manageability of tools, possibility of restoring a structure without interrupting its utilization by users and durability. In spite of many advantages of FRP laminated composites over traditional materials complex me- chanics involved in laminated fibrous composites poses new challenges for the construction industry. 6 APPLICATION OF FRP LAMINATED COMPOSITES IN STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING Structural safety is always a crucial aspect, especially in seismic areas where social and economic concerns are very high. More resources are being devoted to the retrofit and upgrade of existing structures. The widespread use of the FRP system is in the restoration and seismic strengthening of historical masonry buildings. The use of laminated composites is thus becoming more widespread as an optimal innovative system able to reduce the seismic vulnerability of reinforced concrete structures. It ensures an effective confinement of concrete. The use of laminated composites is also very effective in case of urgency, for safety and temporary preservation of structures damaged during special events. Structures having strategic interest and identified as sensitive objectives (in case of explosion risk, terrorist or attempted attacks, etc), the adoption of laminated composites can help to limit damages to persons and structures. FRP laminated composites can be efficiently used where a fast installation is a crucial factor, such as during military/army operations etc. The use of FRP laminated composites in the aerospace and automobile industries is now wellestablished and gaining momentum in structural applications such as buildings, bridges and marine applications. The use of FRP laminated composite in structural applications is discussed along with significant masonry, reinforced concrete building elements and bridge superstructure developments. The outlook for FRP laminated composites is very promising in structural engineering. FRP laminated composites offer a number of advantages over traditional materials and as such can be a viable alternate solution in civil engineering structures. 7 PREFERENCES Abdulahad, E., Panichkov, D. and Rangelova, F., 2007. GFRP reinforcement for concrete beam – an experimental investigation, International conference, Patras, Greece. Abdulahad, E. and Panichkov, D., 2007. Stress state of reinforced concrete beams, reinforced with conventional steel and reinforced with carbon fiber rebars, UACG, Sofia, Bulgaria. Panichkov, D., 2001. Investigation and testing of construction structures and equipments, UIK, Sofia, Bulgaria. Panichkov, D., 1988. Guidance of testing of the construction structures and equipments, Technika, Sofia, Bulgaria. Venkov, V., Ignatiev, N. and Nedelchev, V., 1988, Rehabilitation and strengthening of solid structures of buildings, Technika, Sofia, Bulgaria. Darter, M. and Smith, K. 2003. Life cycle cost analysis, ERES Consultants, a Division of Applied Research Associates, Inc, Vol.6, No 4, pp.1-3. Fenwick, J. M., and Rotolone, P. 2003. Risk Management to Ensure Long Term Performance in Civil Infrastructure, 21st Biennial Conference of the concrete institute of Australia, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 647-656 Mearig, Tim, Coffee, Nathan and Morgan, M. 1999. Life cycle cost analysis handbook”, State of Alaska – Department of Education & Early Development, 1st Edition, 28 pages. Azama, S. 2000. Application of learning curve theory to system acquisition. Belkaoui, A. 1986. The Learning Curve: a management accounting tool, Quorum Books, Westport, Connecticut. Cassity. 2000. Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bridge Decks. Creese, R.C., M. Adithan, and B.S. Pabla. 1992. Estimating and Costing for the Metal Manufacturing Industries, Marcel Dekker Inc., New York. Creese, R. C. 1999. Overcoming Composite Cost Differentials by Life-Cycle Costing, Proceeding of Conference on Polymer Composite: 110-116, Parkersburg, West Virginia, 19-21 April 1999. Ehlen, M.A.and H.E. Marshall. 1996. The Economics of NewTechnology Materials: A Case study of FRP Bridge Decking, NISTIR 5864, U.S. Department of Commerce. Ehlen, M.A. 1997. Life-Cycle Costs of New Construction Materials, Journal of Infrastructure Systems, Dec. 1997: 129133. Ehlen, M.A. 1999. Life-Cycle Costs of Fiber-ReinforcedPolymer Bridge Decks, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, August 1999 Nystrom, H., Watkins, S.E., Namni, A., and Murray, S. Financial Viability of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Bridges. O’Connor, J.S. 2001. New York’s Experience with FRP Bridge Decks. Polymer Composites II 2001: Applications of composites in infrastructure renewal and economic development. CRC Press, NY. Ostwald, P.F. 1984. Cost Estimating, Prentice Hall, New Jersey. Sahirman, S., R.C. Creese, and H. GangaRao. 2002. Economic Feasibility of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Bridge Decks. Tang, B. 1997. Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites Applications in USA, Proceedings of the First Korea/USA Road Workshop. Tang, B. and W. Podolny. 1998. A Successful Beginning for Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Composite Materials in Bridge Applications, FWHA Proceedings of International Conference of Corrosion and Rehabilitation of Reinforced Concrete Structure.