FORMAT:

advertisement

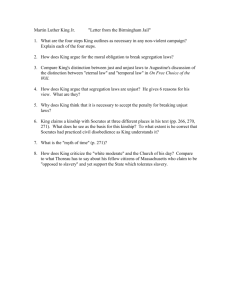

FIRST WRITING ASSIGNMENT: PHILOSOPHY 230, F09 Clark Wolf DUE: Beginning of class, 29 September. FORMAT: This assignment must be neatly typed or printed on a word-processor. It should be between 7001000 words long (about two pages of text). Please do not use a folder or paper cover-- just staple your paper in the upper left-hand corner. Your name should appear only at the top of the back of each page of your paper. Please staple the two pages together. ASSIGNMENT: Epicurus believed that philosophy is practically useful, and that the study of philosophy can help us to live happier and more pleasant lives. One way in which philosophy can accomplish this is by relieving us of burdens that make life worse, and one such burden is the fear of death. Epicurus believed that fear of death makes life worse for many people, and that a proper understanding of death would eliminate such fear. In his Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus offers a philosophical argument against the fear of death: "Get used to believing that death is nothing to us. For all good and bad consists in sense experience, and death is the privation of sense experience. Hence a correct knowledge of the fact that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life a matter for contentment, not by adding a limitless time [to life] but by removing the longing for immortality. For there is nothing fearful in life for one who has grasped that there is nothing fearful in the absence of life. Thus, he is a fool who says that he fears death not because it will be painful when present but because it is painful when it is still to come. For that which while present causes no distress causes unnecessary pain when merely anticipated. So death, the most frightening of bad things, is nothing to us; since when we exist death is not yet present, and when death is present, we do not exist. Therefore it is relevant neither to the living nor the dead, since it does not affect the former, and the latter do not exist. But [most people] flee death as the greatest of bad things and sometimes choose it as a relief from the bad things of life. But the wise man neither rejects life nor fears death. For living does not offend him, nor does he believe not-living to be something bad. And just as he does not unconditionally choose the largest amount of food but the most pleasant food, so he savors not the longest time but the most pleasant. He who advises the young man to live well and the old man to die well is simpleminded, not just because of the pleasing aspects of life, but because the same kind of practice produces a good life and a good death." [Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus, ] In this passage, Epicurus argues that we should not fear death. What is Epicurus’ argument against the fear of death? What reasons and evidence does he offer in favor of the conclusion that we should not fear death? What kind of argument is Epicurus offering anyway, and is his argument rationally persuasive? Your assignment is to explain Epicurus' argument in your own words, and then to evaluate its success or failure. Your paper should have two parts: Part I: In your own words, sympathetically reconstruct Epicurus' argument for the claim that we should not fear death. Do this first in prose, explaining what you take to be Epicurus’ main point and the reasons he offers. Make sure that you present the argument fairly. Then in Part II, put Epicurus argument into standard form with the premises clearly separated from the conclusion. In putting this argument in standard form, you should leave out any claims that are not directly relevant to the conclusion that we should not fear death. You may decide that Epicurus offers several independent arguments against fear of death in this passage: if so, you may interpret this passage in terms of more than one standard-form argument. Part III: In a page or so, evaluate Epicurus' argument. Is it convincing? What unstated assumptions does the argument employ? Are you persuaded that death is not to be feared? Are the reasons Epicurus offers good ones? How would a skeptical critic respond to Epicurus’ argument? Are there good reasons to reject Epicurus’ account of death, and why death is not to be feared? Do we have reason to reject the premises, or the inference from those premises to the conclusion? Whether you agree or disagree with Epicurus' argument, justify your evaluative claims with relevant arguments and points. Do not simply argue that the conclusion is false-- your paper should examine the reasoning used to support that conclusion. Nota Bene: For the purpose of this assignment, you should accept Epicurus’ assumption that death is nonexistence-- nothingness. You should spend your time criticizing Epicurus’ argument in its own terms, not on the basis of a conception of ‘death’ that Epicurus would not have accepted. Your entire paper should be no more than two single-spaced pages long, in 12 point Times Roman type and with normal margins. It should certainly be no longer than 1000 words. EXAMPLE: On the next page is an example of a student response to a writing assignment very similar to the one you'll complete. In preparing your first writing assignment for our class you may find it useful to look this over to give you a better idea of the standards and expectations. EXAMPLE ASSIGNMENT: The "Lyre Argument" In Republic I In Plato's Republic from 348a to 350e, we find Thrasymachus arguing that complete injustice is more profitable than complete justice, since the unjust person will always 'get more.' (Thrasymachus seems to agree with the view that whoever has the most stuff when s/he dies wins.) In the course of his response, Socrates offers an argument that employs the example of a musician stringing a "lyre" (a kind of harp). Very briefly and clearly explain Socrates argument, focusing exclusively on these few pages. First, sympathetically reconstruct Socrates counter argument [esp. 349d-350] in which he attempts to refute Thrasymachus's claim that 'the unjust person will be better off, since the unjust will get more.' Express the core of this argument in your own words. Second, in a page or so, evaluate this argument: Is it convincing? Are there weak premises, or questionable patterns of inference? Does the argument succeed or fail? (EXAMPLE: STUDENT RESPONSE ON NEXT PAGES) Otis Redding, Philosophy 2009 First Writing Assignment: The Lyre argument in Plato's Republic, Book I. PART I. The Argument: In Republic I, Thrasymachus argues that unjust people are wise and good, and that those who are just are naive and foolish [349d]. He justifies this claim with an argument in which he tries to show that the unjust person will be better off, since the unjust will get more than the just. Thrasymachus characterizes just people as those who (i) don't want to get the better of other just people [349b-c], (ii) won't try to over reach a just action [349b], and who (iii) want to "out do" the unjust, not the just [349c]. Unjust people, he claims, are those who (i) want to outdo both the just and the unjust [349c-d], and who (ii) try to "overreach" the just and unjust alike [349d]. Socrates argues that if these claims were true, it would follow that the unjust person must be like other people who are also good and wise, while the just person would be unlike such people [349d-e]. Thrasymachus agrees. Socrates strategy is to consider other people who are good and wise, to see whether they're more like the just or the unjust. Socrates claims that neither the good musician [who is "wise in music"] nor the good physician [one who is "wise in medicine"] tries to "outdo" others in tuning a lyre, or in healing the sick [349e-350]. The musician tries to achieve proper tuning, the physician aims at proper health. In general, those who are wise do not try to "get the better of" those who are wise like themselves- they try to make choices in the same way that other wise people would make them [350b]. They do, however, try to make better choices than those who are not wise. As Thrasymachus has characterized the unjust person, the unjust will try to get the better both of those who are like and unlike him [350c]. It follows that at least in this respect, the unjust person is not like some other good and wise people. It follows that the unjust person cannot be said to be wiser or better off, even if such a person does have more wealth and power. PART II: Standard Form Interpretation of the Argument: 1) Suppose that the Unjust are wise and good. 2) If unjust people are wise and good, then they will be like other wise and good folks. 3) Good musicians & good doctors are wise and good. 4) Good musicians & doctors don't try to overreach one another. 5) But unjust people try to overreach one another. 6) Therefore, the Unjust are NOT wise and good. PART III. Evaluation: The argument does not conclusively show that the unjust person is not good and wise, what it shows is that Thrasymachus's argument is insufficient to prove that the unjust person will be good and wise. But in the context, this is all Socrates needs to show. Socrates argument seems to equivocate in its use of the notion that the just person will not "overreach" the ideal place. A case in point is his image of a musician tuning a lyre. The analogy serves his argument well: if a musician tried to out-do others by turning the tuning peg as far as possible, she would "overreach" the mark, and wind up (forgive the pun) with an out of tune instrument. Expert musicians don't try to 'overreach' one another by tuning their lyres more tightly. A physician would be a fool who tried to "overreach" the success of another physician (to make the patient more than perfectly healthy-- there's no such thing). But experts do try to 'overreach' one another by trying to play better than other experts. Socrates needs an additional argument, to show that justice is a goal like 'health' or 'having an in tune lyre,' not like the goal of 'being the best.' Some goals are insatiably good: the more the better. Is what the unjust person will "get more of" satiable, like health & proper intonation, or insatiable like "skill?" What the unjust person will get, according to Thrasymachus, is wealth and power. Is this something one can have too much of, so that getting more will be like overreaching the point where a lyre is in tune? Or are wealth and power more like "virtue" and "good," so that we can never have too much? The validity of the argument depends on an answer to this (as yet) unexamined question. Further, the argument seems to miss an important idea behind Thrasymachus's argument: a clever person should be able to get more than a foolish one. So if people who are just allow themselves to be taken in by those who are not, then they can't be very clever. When Thrasymachus says that the unjust person is wise, he means that such people are clever: good at getting what they want. In deal-making, such people will get the better of those they bargain with. Socrates, on the other hand, has in mind the kind of wisdom that makes a person good at a particular craft. Still, it's easy to imagine a person who is knowledgeable about one subject, but hopelessly naive when it comes to deal-making, so that she ends up worse off when she deals with others who are clever and unscrupulous. Socrates's point is that money is not as valuable as the true happiness one gets from living well, so while the foolish unjust person will strive for money and power even at the expense of true happiness, the wise person will go for true happiness, and won't be misled by the desire for more stuff, whether money or power. Socrates doesn't explicitly argue for these claims here, but the argument does not entirely succeed without them. In spite of these limitations, Socrates does effectively show that Thrasymachus's argument was faulty. To strengthen his own argument, it must be shown that (i) justice in a person is like proper tuning in a lyre, so that one can "overshoot the mark," (ii) it is better to be wise than merely clever, and (iii) those who are wise are better off than those who are merely clever, even if they are less wealthy and powerful. Plato does take up each of these issues later in The Republic. The General Form of the Argument is not formally valid. We can see this because it is possible to construct a counterexample: an argument with the same form, with true premises, and with a false conclusion. For example: 1) Suppose that Mexican Hairless Dogs are Mammals. 2) If Mexican Hairless Dogs are mammals, then they will be like other Mammals 3)Sheep and Bears are Mammals. 4)Sheep and Bears have Hair. 5)Mexican Hairless dogs DON'T have hair... 6) Therefore, Mexican Hairless dogs are NOT mammals. (This short essay is about 950 words long.)