The Interaction of Two Coastal Plumes and its Effect on the Transport

of Alexandrium Fundyense

by

Christie L. Wood

B.S. Mathematics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005

B.S. Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

and the

WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION

September 2007

C Christie L. Wood. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper

and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now

known or hereafter created.

Signature of Author:

Certified by

,

Joint Program in Physical Oceanography

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

September 2007

C

Glenn R. Flierl

Professor of Oceanography

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by

4

At affaele Ferrari

OF TEOHNOLOGYV

OCT 222007

LIBRARIES

MASSACgraphy

Chairman, Joint Committee for Physical Oceanographv

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

ARCHVES

The Interaction of Two Coastal Plumes and its Effect on the Transport

of Alexandrium fundyense

by

Christie L. Wood

Submitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Woods Hole

Oceanographic Institution in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science

Abstract

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) of A.fundyense, more commonly known as "red

tides", are a serious economic and public health concern in the Gulf of Maine. Until

recently, there was very little known about the mechanisms regulating the observed

spatial and temporal distributions of A.fundyense in this region. In the beginning of this

work a review of previous research on A.fundyense and the mechanisms controlling their

spatial and temporal distributions in the Gulf of Maine is presented. One of the major

conclusions that can be drawn from previous work is that a thorough understanding of the

interactions between river plumes is essential to our understanding of this problem. The

rest of this thesis intends to contribute to the understanding of these plume interactions

and their effect on the transport of A.fundyense. Mixing between two interacting river

plumes with various buoyancies is investigated through laboratory experiments. These

experiments indicate that under these idealized conditions, there was little mixing

between the plumes after their initial interaction. A numerical model is used to explore

the effects of river mouth size and flux variations on the interaction between two plumes.

It is shown that based on river mouth geometry and flow rates the effect of the southern

plume on the path of the northern plume can be predicted. In the final section a simple

NP model is coupled with the physical model to explore the possible effects of river

plume interaction on the distribution of A. fundyense. Based on our modeled results, it

appears as if the southern river under certain conditions could temporarily act as a shield

preventing A.fundyense from reaching the coast but that this was not a permanent state.

Thesis Supervisor: Glenn R. Flierl

Title: Professor of Oceanography, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to study physical oceanography in

the MIT/WHOI Joint Program. I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Glenn Flierl,

for his guidance and for allowing me plenty of research freedom. Because of him my

research experience in the joint program a positive one. I would like to thank Dennis

McGillicuddy for introducing me to the Red Tide issue in the Gulf of Maine, for allowing

me to join him on his research cruise OC425 and for all of his additional advice.

There are several people who made the experimental section of this work

possible. First and foremost I would like to thank Claudia Cenedese for advising me on

this section of my thesis and giving me access to the geophysical fluid dynamics lab at

WHOI. I would like to also thank Valentina for her throrough preliminary studies which

served as a guide for my study. I would also like to thank Keith Bradley who was always

willing to help me in the lab and whose unwavering pleasant demeanor made me look

forward to work every day.

I would also like to thank several people who I worked with on research not

included in my thesis but whose time and effort significantly contributed to my

education. Jim Lerczak introduced me to the Regional ocean Modelling System (ROMS)

and to estuarine studies. I spent a summer working with Amy Bower on eddies in the Red

Sea. Larry Pratt introduced me to the fascinating world of hydraulics. I would like to

thank him for his guidance on my class project and for being my advisor during my

summer student fellowship. I would also like to thank Carl Wunsch for having the

seminar on ocean observation and for all of his help and advice when I was in tough

situations.

There were many other people in the Joint Program who I would like to thank. I

would especially like to thank the following staff: Mary Ellif, Ronni Schwartz, Carol

Sprague, Marsha Gomes, Julia Westwater and Laishona Vitalli. I would also like to thank

my wonderful classmates in both the joint program and in paoc: Peter Sugimura, Evgeny

Logvinov, Jinbo Wang, Andrew Barton, Martha Buckley, Eunjee Lee and Scott Stransky.

I special thanks to Evgeny for getting me through the more difficult times and to Jinbo

for being the best officemate any one could ask for. My friends in the physical

oceanography department for all of their advise and support: Stephanie Waterman,

Tatiana Rykova, Katie Silverthorne and Jessica Benthuysen. A special thanks to my three

best friends in the joint program, Whitney Krey, Christine Mingione and Colleen Petrik,

who were always available for a drink at the Kidd and other stress relieving activities. I

would also like to thank my other friends in the joint program: Kevin Cockrell, Kate

D'Epagnier, Caleb Mills, David Stuebe and Matt Jackson.

I would also like to thank several of my family members for all of their

encouragement and support. A special thanks to my mother and father for their

continuous support and encouragement. I'd like to thank my grandfather (known to some

as the 'Old Fisherman') who was always eager to discuss my research and share his

knowledge of the ocean with me. I would also like to thank my roommate Karen Keller

and my kitten Nami who always seem to be at home ready to cheer me up.

Contents

1

Introduction

9

2

Background

13

3

2.1

Life Cycle ofAlexandriumfundyense ...............................

2.2

Alexandriumfundyense Cyst Distribution ...............

2.3

The Gulf of Maine Coastal Current .......................................

17

2.4

The "Plume Advection Hypothesis" ................................

19

2.5

The "Cyst Source" Hypothesis ....................................

22

2.6

Possible Mechanisms for Entrainment .............................

24

2.7

Summary .......................

....

.....................

13

..........

.

15

....... 27

Laboratory Experiments

29

3.1

Apparatus..........................................................

30

3.2

Procedure ....................................................

32

3.3

Results ..............

. ....

........

................

........

3.3.1

Summary of Experiments ....................................

3.3.2

Vertical Plume Structure ..

33

33

..................................... 35

3.3.3

3.4

37

Mixing ...............................................

42

Summary and Discussion .......................................

43

4. Physical Numerical Model

4.1

Model Formulation .........................

.................. 44

4.2

Base Case ................................

.................. 46

4.3

Variations in River Mouth Geometry ...........

.................. 52

4.4

Variations in River Fluxes ....................

.................. 58

4.5

Summary and Discussion .................

.. ................... 66

65

5. Coupled Biological Physical Model

5.1

Biological Model Formulation .................................

65

5.2

Coupled Biological-Physical Model ..............................

68

5.4

5.2.1

Model Setup ...............................

5.2.2

Results .................

............................

Summary and Discussion .......................................

............

68

69

78

Chapter 1

Introduction

Harmful algal blooms (HABs), more commonly known as "red tides", are a

serious economic and public health concern. In the Gulf of Maine the most serious

problem associated with HABs is paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP). PSP, a potentially

fatal neurological disorder, is caused by human ingestion of shellfish (e.g., mussels,

clams, oysters and scallops) that have consumed the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium

fundyense. The onset of symptoms is rapid and, in the most severe cases, PSP results in

respiratory arrest within 24 hours of consumption of the toxic shellfish. There is no

known antidote for PSP, thus making blooms of A. fundyense a major threat to public

health. The Journal of Shellfish Research tried to emphasize the seriousness of the red

tide problem to their readers through a somewhat comical cartoon on one of their covers

(fig. 1-1). Here they show a bloom of A. fundyense as an ominous dark mass staring at the

shellfish who, out of fear of becoming toxic, have sought refuge on the shore. In response

to the threat of red tide, regional monitoring programs have been established to sample

coastal shellfish beds regularly and test for PSP toxins. It has been demonstrated that

toxicity in the mussel Mytilus edulis is a good indicator of the presence of A. fundyense

cells (Shumway et al., 1988). Discovery of PSP toxins leads to shellfish bed closures,

causing a serious economic hardship to the coastal fishing industries.

Figure 1-1. A cartoon from the cover of Journal of Shellfish Research Vol. 7, No.4

Blooms of the toxic dinoflagellate A. fundyense are a recurring feature in the Gulf

of Maine. Following an outbreak in Canada in 1957, five monitoring stations were

established in the coastal Maine area and were expanded to 119 sampling stations after a

year of high toxicity in 1974 (Shumway et al., 1988). Blooms of A. fundyense have

occurred every year since 1958 along the southern coast of Maine between the months of

May and October. Blooms began appearing along the northern coast of Massachusetts in

1972 and have occurred every year since, excluding 1987 (Shumway et al., 1988).

Anderson (1997) reviewed studies of the bloom dynamics with focus on various

subregions in the GOM. Observations show that peak toxicity in the western GOM

occurs early in the bloom season (May-June) and is less severe than peak toxicity in the

eastern GOM, which occurs later in the bloom season (July-August). It has also been

noted that the Penobscot Bay region, which separates the eastern and western GOM, and

is sometimes referred to as the "PSP sandwich" (Shumway et al., 1988), is usually devoid

of PSP.

Until recently, there was very little known about the mechanisms regulating the

observed spatial and temporal distributions of A. fundyense in the Gulf of Maine. There

were several studies that focused on sub-regions of the Gulf of Maine (e.g. Anderson and

Keafer, 1985; Franks and Anderson, 1992a; Franks and Anderson, 1992b; Martin and

White, 1988; White and Lewis, 1982). The 1997-2001 Ecology and Oceanography of

Harmful Algal Blooms-Gulf of Maine (ECOHAB-GOM) project greatly added to the

understanding of the interconnections between the regional bloom dynamics of A.

fundyense in the Gulf of Maine. In the second chapter of this thesis I present a review of

previous research on A. fundyense and the mechanisms controlling their spatial and

temporal distributions in the Gulf of Maine. Much of the research discussed in this

section was part of the ECOHAB-GOM project. One of the major conclusions that can be

drawn from previous work is that a thorough understanding of the dynamics of river

plumes and interactions of river plumes is essential to our understanding of this problem.

The rest of this thesis intends to contribute to the understanding of these plume

interactions. In Chapter 3, mixing between two interacting river plumes with various

buoyancies is investigated through laboratory experiments. In chapter 4 a numerical

model is used to explore the effects of river mouth size and flux variations on the

interaction between two plumes. In both Chapter 3 and 4 the possible effects on the

transport of A. fundyense are discussed and in Chapter 5 a simple NP model is coupled

with the physical model to explore more explicitly the possible effects of river plume

interaction on the distribution of A. fundyense.

Chapter 2

Background

2.1 Life Cycle of Alexandriumfundyense

Anderson (1998) describes the life cycle of Alexandrium species (figure 2-1). The

life cycle involves both sexual and asexual reproduction. During asexual reproduction,

division by binary fission yields vegetative motile cells, which contribute to the

development of blooms. Sexual reproduction begins with the formation of gametes,

which fuse to form swimming zygotes, which then become dormant resting cysts. The

species Alexandrium fundyense also has another resting stage called a "temporary cyst",

which is a result of a sudden shift to unfavorable conditions. However, the following

discussion of A. fundyense cysts refers to the dormant resting cysts, which are a

mandatory stage in the life cycle and critical to our understanding of the population

dynamics of this species.

There are several factors that regulate how long a cell will remain as a dormant

resting cyst. Internally, there is a mandatory maturation period (Anderson, 1980) and an

endogenous annual clock (Anderson and Keafer, 1987). In addition, mature cysts will

remain in this resting state (known as "quiescence") while conditions in the overlying

waters are unfavorable for growth. There are several external factors which have been

found to control the germination of mature A. fundyense cysts. If the temperature of the

overlying water is above or below a range that allows germination, the cells will remain

quiescent (Anderson, 1998; Anderson et al., 2005b). Light (Anderson et al., 1987;

Anderson et al., 2005b) and oxygen (Anderson et al., 1987) also affect the rate of

germination. If overlying water conditions remain unfavorable for germination, or if cells

are buried deep in the anoxic sediments, the cysts can remain quiescent for years. How

long cysts can live is difficult to determine; however, Keafer et al. (1992) suggest that the

half life ofAlexandriumfundyense cysts in anoxic sediments is approximately five years.

Once germination occurs, the overlying water column is inoculated with cells and, as

previously mentioned, the cells begin to divide via binary fission creating a bloom.

Clearly, the location of cyst accumulations in the surface sediments (known as

"seedbeds") is important in determining the location of the resulting blooms.

-F-

/Cs

I8

e ý?

f

I

Iq

14MA

i,;

#15

xi

wri ·

Figure 2-1. Life cycle diagram for Alexandrium fundyense The labeled stages are: (1)

motile vegetative cell; (2) temporary cyst; (3) "female" and "male" gametes; (4) fusing

gametes; (5) swimming zygote; (6) resting cyst; (7&8) motile germinated cell; (9) pair of

vegetative cells after division by binary fission (Anderson, 1998).

2.2 Alexandrium fundyense Cyst Distribution

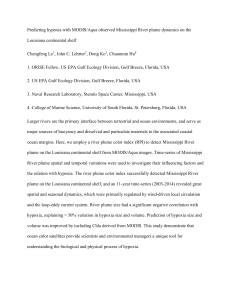

Anderson et al. (2005b) produced the first Gulf-wide survey showing the

abundance of cysts in bottom sediments (fig. 2-2). The data used for this map came from

multiple surveys (White and Lewis, 1982; Martin and Wildish, 1994; J. Martin,

unpublished data; Anderson et al., 2005b); however, most of the samples from between

the Bay of Fundy and the western extreme of the sampling domain are from the 1997

ECOHAB-GOM survey. The cyst distribution map clearly shows three distinct zones of

high cyst concentration. One of these seedbeds is located near Grand Manan Island at the

mouth of the Bay of Fundy, where maximum abundance is close to 2000 cysts /cm3

(Anderson et al., 2005b). There is evidence that the Bay of Fundy cyst bed is a persistent

feature (Anderson, 2005b; Martin and Wildish, 1994; J.Martin, unpublished data). This

could be explained by the eddy system that lies above this seedbed and is able to retain a

fraction of the vegetative cells produced by germination from this seedbed, resulting in

high cell concentrations in the overlying waters (Martin and White, 1988). Anderson et

al. (2005b) propose that this area serves as an "incubator" for the region, with many of

these retained cells depositing new cysts at the end of the bloom season to replenish the

underlying seedbeds. In the cyst map by Anderson et al. (2005b) there were also high

concentrations of cysts offshore of both Penobscot and Casco Bays. Anderson et al.

(2005b) observed interannual variability in cyst abundance at these locations, which is

attributed to interannual variations in cyst deposition. The circulation in the Gulf of

Maine suggests possible links between the location and interannual variability of these

seedbeds and the seedbed in the Bay of Fundy.

45

cysts/cm

600

500

44

400

300

-J

43

200

42

100

0

-71

-70

-69

-68

Longitude

-67

-66

-65

Figure 2-2. Distribution and abundance ofAlexandriumfundyense cysts in the

surface sediments (top cm) of the Gulf of Maine(Anderson et al. 2005b).

3

2.3 The Gulf of Maine Coastal Current

The Gulf of Maine (GOM) is a mid-latitude marginal sea bounded by New

England and southeastern Canada. The general circulation of the GOM is cyclonic

(Bigelow, 1927). The major cyclonic gyre in this region is centered on the Jordan Basin

and is sometimes referred to as the Jordan Basin Gyre (Pettigrew et al, 1998). Another

dominant feature of the circulation is a complex coastal current system that flows from

the gulf coast of Nova Scotia to Massachusetts (Brooks, 1985). The Gulf of Maine

Coastal Current (GMCC) is highly variable and is thought to consist of several branches

(Pettigrew et al., 1998).

The two main branches of the GMCC are referred to as the Eastern Maine Coastal

Current (EMCC) and the Western Maine Coastal Current (WMCC). The EMCC extends

from the mouth of the Bay of Fundy along the coast of Maine to Penobscot Bay. A major

portion of the EMCC turns offshore and contributes to the cyclonic circulation of the

basin and another portion continues southwestward to join with the WMCC (Pettigrew et

al., 1998 ). The EMCC could be split into two parts (Keafer et al., 2005b): a low-salinity,

coastally trapped buoyant current originating from upstream low-salinity waters from the

St. John river, and a more offshore branch which originates from Scotian shelf waters.

The WMCC extends from the Penobscot Bay to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The WMCC

is augmented by river outflow from the Kennebec, Androscoggin, Saco and Merrimack

rivers. This low-salinity water is sometimes referred to as the "plume" (Anderson et al.,

2005a). The WMCC is therefore also made of two distinct water masses: the plume and a

more offshore component. There is a branch point in the WMCC near Cape Ann,

Massachusetts, where some of the current enters Massachusetts Bay and the rest travels

along the eastern edge of Stellwagen Bank. The latter segment undergoes another

bifurcation at Cape Cod with some of the current extending south towards Nantucket and

the other portion which travels to and around Georges Bank . Figure 2-3 shows a

schematic of the circulation in the GOM as described by Keafer et al. (2005b), which

builds upon previous schematics, such as those by Bigelow (1927) and Brooks (1985).

44

43

42

41

-71

-70

-69

-68

-67

-66

Figure 2-3. General near-surface circulation of the Gulf of Maine (Keafer et al., 2005b).

The degree of connection between the two main branches of the Gulf of Maine

Coastal Current appears highly variable (Pettigrew et al., 1998). Pettigrew et al. (2005)

investigated the GMCC from 1988 to 2001 using extensive hydrographic surveys, current

meter moorings, tracked drifters and satellite thermal imagery. The degree to which the

EMCC veered offshore or joined the WMCC during the summer months varied greatly

during the three year study. In 1998, almost all of the EMCC was directed offshore,

whereas there was a nearly continuous throughflow between the EMCC and WMCC in

2000. Keafer et al. (2005b) suggest that part of the inshore branch of the EMCC may

flow directly into the plume of the WMCC. They refer to this continuum of fresh water as

the "inside track" or the Gulf of Maine Coastal Plume (GOMCP). A study by Geyer et al.

(2004) shows that the volume of freshwater transport by the plume in the western Gulf of

Maine exceeds the local riverine inflow of fresh water by 30%, suggesting a significant

contribution from the St. John and further supporting the existence of a GOMCP.

2.4 The "Plume Advection Hypothesis"

The complex and highly variable hydrography of the Gulf of Maine and the

complicated population dynamics of A. fundyense make the study of the bloom dynamics

of this dinoflagellate very challenging. Based on observations of toxicity at five stations

in the western Gulf of Maine (see figure 2-4) over three bloom seasons, Franks and

Anderson (1992a) showed that toxic shellfish outbreaks typically showed a north-tosouth progression and A. fundyense cells were predominately observed in the low-salinity

waters (highest concentrations were located in waters < 31.5 psu). A peak in river

discharge of the Androscoggin and Kennebec rivers prior to the detection of toxicity

suggests that these rivers are the source of this fresh water. This led Franks and Anderson

(1992a) to hypothesize that this annual southward progression of toxicity is a result of

alongshore advection of Alexandriumfundyense in the coastally trapped buoyant plume

formed by river discharge (this hypothesis is often referred to as the "plume advection

hypothesis").

Figure 2-4. The station locations for the study by Franks and Anderson (1992a).

Franks and Anderson (1992a) also suggested that alongshore winds had an

important effect on the motion of the plume. It was observed that downwelling-favorable

(southwestward) winds increased the speed of the plume and held the plume to the coast

increasing the intensity and alongshore extent of toxicity. Upwelling-favorable

(northeastward) winds decreased the speed of the plume and forced the plume offshore

potentially causing it to separate from the coast (see figure 2-5). Separation would result

in a decrease in toxicity of intertidal shellfish. In addition to wind direction, the volume

of discharge from the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers was also shown to have a

significant impact on plume velocities and, in years of high river discharge, it was

observed that toxicity patterns were relatively independent of the wind patterns, whereas,

in years of low river discharge, the wind had a greater influence (Franks and Anderson,

1992a).

N

1.

4D

41Rr

ND

Figure 2-5. Surface (left) and vertical across-shelf (right) plots of salinity distribution of

a buoyant coastal plume subject to no wind stress (top), downwelling-favorable wind

stress (middle) and upwelling-favorable wind stress (bottom) (Franks and Anderson,

1992a).

Franks and Anderson (1992b) further tested the plume-advection hypothesis of

Franks and Anderson (1992a) using historical records of shellfish toxicity, river outflow

and windstress from 1979 to 1989. As predicted by the plume-advection hypothesis,

every toxic outbreak in Massachusetts was preceded by both an outbreak in Maine and an

increase in the discharge of the Androscoggin River. The observations from 1985 present

the only contradiction to the north-south progression of the "plume advection

hypothesis", showing almost simultaneous outbreaks of toxicity over a wide section of

the coast.

2.5 The "Cyst Source" Hypothesis

There were several issues that were left unresolved by Franks and Anderson

(1992a and 1992b) most notably the origin of the A. fundyense cells. Franks and

Anderson (1992a) suggest that the cells enter the plume in the western gulf of Maine near

the mouth of the Kennebec River, but did not suggest a source for these cells. Anderson

et al. (2005a) confirmed the general elements of the plume advection hypothesis and

refined this conceptual model by defining two potential source populations: those

originating from the offshore benthic cyst populations (McGillicuddy et al., 2003) and

those being transported to the WMCC from the EMCC (Townsend et al., 2001).

Several studies provide evidence that the EMCC acts as an important pathway for

A. fundyense cells to enter the Western Gulf of Maine. Several surveys by Martin and

White (1988) indicate westward penetration of high cell densities from the "incubator"

region east of Grand Manan Island into the EMCC and Townsend et al. (2001) note that

the highest cell concentrations in the Gulf of Maine are observed in the cold, nutrient-rich

waters of the EMCC. Anderson et al. (2005b) suggest that some of the cells transported

in the EMCC become entrained in the western GOM waters, where they may cause

immediate toxicity, while others are deflected offshore. As previously mentioned, the

degree to which the EMCC flows into the western GOM is highly variable and this could

have a significant impact on the intensity of toxicity. Leursen et al. (2005) show that low

toxicity in the western GOM occurred when a strong front developed, also referred to as a

period where the "door is closed" (Leursen, 2001), and, in years when a weak front

develops, the "door is open" and high toxicity was observed in the western GOM.

Leursen et al. (2005) conclude that the EMCC has a significant effect on the intensity of

toxicity in the western GOM either by advection of nutrient-rich water or by direct

transport of cells into the WMCC. Keafer et al. (2005b) observed the highest abundance

of A. fundyense within the fresher waters of the EMCC, which originate from the outflow

of the St. John that flows over the seedbed east of Grand Manan Island. They therefore

suggest that cells could be transported directly from the EMCC into the WMCC via the

GOMCP described earlier. The GOMCP can be partially deflected offshore due to

upwelling-favorable wind stress, thus adding another source of variability to the

distribution of A. fundyense blooms.

There is evidence that offshore cyst beds also play an important role in blooms of

A. fundyense in the western Gulf of Maine. A study by McGillicuddy et al. (2003)

suggests that, during upwelling-favorable winds, the river plume in the western GOM

thins and can extend far enough offshore to be over the seedbeds observed near Casco

Bay and Penobscot Bay, allowing the possible entrainment of these cells into the plume.

With subsequent downwelling-favorable winds, the plume would return to the coast

transporting the cells to the shellfish beds. A study by Stock et al. (2005) further supports

the importance of offshore cyst beds. Results from their coupled physical-biological

model suggest that the cysts germinated from offshore seedbeds could account for the

observed timing and magnitude of A.fundyense blooms in the spring in the western

GOM. This mechanism could also explain the near simultaneous outbreaks of toxicity

observed in the western Gulf of Maine in 1985 by Franks and Anderson (1992b).

There is an observed west-to-east shift in the center of mass of vegetative cells

that cannot be explained solely by the east-to-west transport of the EMCC and the plume

of the WMCC. Townsend et al. (2001) hypothesized that the A. fundyense cells that enter

the EMCC do not initially flourish due to the deep mixing and turbulence, which limits

the amount of light reaching the cells. However, as the water reaches the west, the water

becomes more stratified which is more favorable for growth. McGillicuddy et al. (2005)

present results from a coupled physical-biological model that suggest another possible

explanation for the west-to-east trend of toxicity. Early in the season they suggest that

temperature could be the major limiting factor in the eastern Gulf of Maine. Higher

concentrations of vegetative cells are observed in the western gulf of Maine primarily due

to higher temperatures and cumulative impact of cysts being transported from the two

major cyst beds located in the Bay of Fundy and offshore of Casco and Penobscot Bays.

During the transition from spring to summer the western Gulf of Maine becomes nutrient

depleted. Nutrient limitation results in the induction of sexuality in A.fundyense, which

leads to the formation of resting cysts (Anderson and Lindquist, 1985). The cyst

accumulations offshore of Penobscot and Casco Bays observed by Anderson et al.

(2005b) are found in the general area where the model predicts nutrient limitiation will

occur. Although the western Gulf of Maine becomes nutrient-limited, growth of

vegetative cells still occurs in the nutrient-rich eastern Gulf of Maine.

2.6 Possible mechanisms for entrainment

Horizontal ocean currents are several orders of magnitude greater than swimming

speeds of plankton; therefore plankton can be considered passive tracers in a lateral

context. In contrast, ocean currents are considerably weaker in the vertical, and thus

plankton, with typical swimming speeds of meters to hundreds of meters per day, are able

to change their vertical position (Hetland et al., 2002). Dinoflagellates like Alexandrium

fundyense are light limited and it is therefore beneficial for them to be able to change

their vertical position. There are several possible mechanisms by which the cells could

enter the plume from the EMCC or from offshore, and they all depend on light-seeking

swimming behavior of Alexandrium fundyense.

The analysis of density surfaces presented in Keafer et al. (2005b) suggests that

cells that are located beneath the surface mixed layer (>10m depth) can be transported

directly beneath the thin river plume and enter the plume via vertical light-seeking

swimming behavior. In another study (Keafer et al., 2005a), temperature and salinity

analysis is used to infer that surface populations at the outer edge of the Penobscot plume

can be subducted underneath the low salinity Kennebec plume and the A. fundyense cells

could enter the plume via vertical light-seeking swimming.

The previous mechanism involves the interaction of two buoyant coastal currents.

In contrast, modeled experiments by McGillicuddy et al. (2003) and Hetland et al. (2002)

suggest mechanisms by which cells may be entrained into a river plume undergoing

offshore and onshore excursions as a result of varying wind conditions. Hetland et al.

(2002) proposed the "frog tongue" hypothesis, which establishes a range of upward

swimming velocities that would allow plankton to enter a plume during upwelling

favorable conditions and then be transported towards the coast during subsequent

downwelling events. In order for plankton to enter a plume, they must swim with a

vertical velocity wp which satisfies

H ,,plume, / T < w, < KI/ H,,,i

where Hp is the thickness of the plume, Hil,,, is the thickness of the mixed layer (where

H,,,x Hp,,,,e - 0(10) ), T is the time between onshore and offshore extremes of the

plume, and K is the magnitude of mixing in the mixed layer (Hetland et al., 2002). This

inequality indicates that the plankton must swim slow enough so that they will be evenly

distributed in the mixed layer and can therefore be subducted under the plume as it moves

offshore. When the plankton are beneath the plume they must swim quickly enough to

enter the plume before it begins to return to the coast. A diagram of this model is seen in

figure 2-6.

TR

C

weak r

I

D

~

(-

OT

t·c-

-- -

- -

- -

-

- -

- -

Figure 2-6. A cartoon illustrating the various stages in the entrainment of a portion of an

offshore plankton patch. The squiggly, straight horizontal and circular arrows, represent

swimming, Ekman transport velocity and turbulent mixing respectively. The dark grey

represents the plankton patch (Hetland et al., 2002).

A CROSS-ISOBATH TRANSPORT MECHANISM

FOR INITIATION OFALEXANDRIUM BLOOMS

UPWELLING

,·

--------

DOWNWELLING

I`~-,.

-., ,,~.r

c~r r

Figure 2-7. Schematic of a proposed mechanism for the entrainment of A. fundyense

cells originating in offshore cyst beds. During upwelling favorable conditions the plume

thins and extends offshore above the cyst beds where newly germinated light-seeking

cells swimming towards the surface can enter the plume. During downwelling favorable

conditions these cells are transported towards shore in the plume. (McGillicuddy et al.,

2003)

McGillicuddy et al. (2003) used a coupled three-dimensional biological-physical

model to investigate how germinated cells from offshore cyst beds could contribute to

nearshore blooms. The model results suggest that under upwelling conditions a plume

may thin and extend far enough offshore to be above the observed cyst beds. This would

allow the newly germinated cysts to be entrained in the plume as they swim vertically

towards the light in order to begin vegetative growth. As the winds become downwellingfavorable the plume moves onshore and thickens thereby exposing the coast to these

toxic cells from offshore. A schematic of this process is shown in figure 2-7.

2.7 Summary

From the research presented, it is clear that the gulf-wide circulation, particularly

the dynamics of the buoyant coastal plumes, and cyst bed locations play an important role

in the distribution of A. fundyense blooms in the Gulf of Maine. Within the Gulf of

Maine, A. fundyense cells are transported within these buoyant coastal plumes which are

part of the two major coastal currents: the EMCC and the WMCC. There is evidence that

these cells originate from the cyst beds in the Bay of Fundy and offshore of Penobscot

and Casco Bays. The EMCC transports these cells from the Bay of Fundy to Penobscot

Bay where it splits into two different branches, transporting cells directly into the western

GOM, where they can become entrained in the WMCC and transported into the western

GOM , or they can be deflected offshore where they become encysted to form the

offshore seedbeds. The germinated cells from these offshore cyst beds can be entrained in

the plume of the WMCC during an upwelling favorable wind event and transported back

to shore where they can cause toxicity in the shellfish beds during a subsequent

downwelling event. The one-way path of A. fundyense cells in the Gulf of Maine suggests

that the self-seeding cyst population in the Bay of Fundy is the cause of persistent

occurrences of toxicity along the coast and that the GMCC is its main means of

transportation. Therefore, in order to understand the variability in the distribution of A.

fundyense , we need to understand the dynamics of river plume interactions that feed this

coastal current.

Chapter 3

Laboratory Experiments

Consider a case where one river plume, carrying A. fundyense, travels along the

coast and comes into contact with another river plume. The first plume could go above,

around or be subducted beneath the second plume. If the first plume goes above the

second plume, then it is possible that the A. fundyense will reach the coast and be

consumed by shellfish. If the plume goes around or is subducted beneath the second

plume the A. fundyense will need to enter the second plume in order to gain access to the

coast. Two possible ways of doing this are through mixing between the two plumes and

through swimming. In this chapter I explore the first possibility by trying to quantify

mixing in a series of laboratory experiments modeling the interaction of two riverplumes

with various densities and flow rates.

3.1 Apparatus

Laboratory experiments were conducted to investigate the interaction between

two coastal plumes. The experimental setup was configured to represent a northern and

southern plume flowing along a vertical wall above a flat bottom.

The experiments were conducted in a cylindrical tank with a diameter of 2.1 m, a

height of 0.45 m and a flat bottom. The tank was rotated counter-clockwise, to simulate

the northern hemisphere, with a fixed rotation rate of f=1. The tank was filled with ocean

water (p = 1.022 g / cm3 ) to a depth of approximately 15 cm.

The two rivers were simulated by pumping buoyant water at a constant rate at two

different locations on the side of the tank. The top view and side views of the

experimental set up can be seen in figure 3-1 and figure 3-2 respectively. The sources

were two pipes with diameters of 1.5 cm located 116 cm apart. In the figure, the northern

river is labeled with an N and the southern river is labeled with an S. To minimize

excessive mixing at the source, foam was wrapped around the end of the pipe.

A conductivity probe was positioned 59 cm away from the southern plume

(labeled with a P in the fig 2.2.1 and fig. 2.2.2). The probe was fixed to the side of the

tank so that it could be moved vertically and perpendicular to the wall of the tank.

Ile

"P

rr·

I

t-:~

I.

,· I

it6

Ii

i

/

S

z

/

· `P

Figure 3-1 Top view of tank set up. N and S indicate the locations of the northern and

southern plumes respectively. P indicates the location of the probe when closest to the

wall. (Graphic made by Valentina)

c

o

cn

a

I:

i:

ii:

ii

i:

i·

ii

210

Figure 3-2 Side view of tank set up. Dimensions are in cm.

3.2 Procedure

The two source waters were created by mixing sea water and fresh water. The

densities of these two fluids were determined with a model DMA58 Anton Paar

densitometer which has an accuracy of 10-5 g/cm 3.

The tank was rotated counter-clockwise at a rotation rate of f =1. After the

ambient fluid reached solid body rotation the two sources were turned on. After the

northern current came into contact with the southern current, a profile was taken near the

wall. The frequency of each profile was 1 point per 0.01 cm and only the downward

profiles were used.

Six mixtures of known densities ranging from that of fresh water to that of ocean

water were made. Their densities were first measured with the densitometer and then with

the conductivity probe. The approximate analytical relationship between voltage and

density is the following second order equation

V = aL

where p* = p -Po,

+a2

+ a3

(3.1)

po is the freshwater density and p ( g/cm3 ) is the density which

corresponds to the voltage V. Using this equation we can find the coefficients which best

fit the density and voltage measurements.

Solving equation 3.1 for density we find

2

P = Po

+

-(a 2 + a - 4ai(a

a+

2a(3.2)3

-V))

(3.2)

Using this equation and the calibration coefficients, voltage profiles were converted to

density profiles.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Summary of Experiments

Six variations of the experiment were done. In each one the densities and flow

rates of each river were changed. A summary of the experiments can be seen in table 3-1.

The table shows the densities (p) of the ocean water and fresh water which were mixed to

make the north and south river waters, the density of the tank water, the flow rate of the

northern plume (Qn) and the flow rate of the southern plume (Qs). The desired or ideal

density, reduced gravity and buoyancy flux for the northern river (pn, g'n, Bn) and the

southern river (ps, g's, Bs) are listed. The reduced gravity is defined as

g'g

(po-p)

o + p)/2

where Po is the density of the tank water. The buoyancy flux is defined as

B = g'Q.

In addition, the experimental values for the density, reduced gravity, buoyancy flux and

the error between the ideal and experimental value of g' for each river are listed.

Experiment

p ocean water

(g/cc)

p fresh water (g/cc)

p tank water (g/cc)

1.021

0.999

1.022

Qn (cc/s)

g'n ideal (g/cc)

Pn ideal (g/cc)

Bn ideal

Pn exp (g/cc)

g'n exp (g/cc)

Bn exp

5

1

1.021

5

1.021

0.950

4.75

Qs (cc/s)

g's ideal (g/cc)

Ps ideal (g/cc)

Bs ideal

Ps exp (g/cc)

g's exp (g/cc)

Bs exp

10

5

1.016

50

1.016

4.934

49.34

1

2

3

1.022

1.022

0.998

0.999

1.021

1.021

Northern Plume

10

10

10

5

1.011

1.016

100

50

1.011

1.016

10.111

4.984

101.11

49.84

Southern Plume

10

10

5

5

1.016

1.016

50

50

1.016

1.016

5.216

4.984

52.16

49.84

4

5

6

1.022

0.998

1.020

1.022

0.998

1.022

1.022

0.998

1.020

10

25

0.995

250

0.998

21.456

214.56

20

25

0.996

500

0.998

22.819

456.38

20

25

0.995

500

0.998

21.456

429.12

10

5

1.015

50

1.015

4.929

49.29

10

5

1.017

50

1.016

5.164

51.64

5

5

1.015

25

1.015

4.929

24.645

Table 3-1 Summary of experiments

3.3.2 Vertical Plume Structure

The density profile taken closest to the wall of the tank is shown in figure 3-3 for

each experiment. Each profile was filtered using a boxcar filter of 30 increments. Plotted

on top of the profile are the experimental densities of the northern plume, southern plume

and the ambient tank water indicated by red, blue, and green lines respectively. The sharp

gradient in density seen near the top of several of the profiles is a result of the probe

coming out of the water.

In these profiles we see various vertical structures. In experiment 1 there appears

to be southern plume water overlying northern plume water with a mixed layer between

these two water masses and between the northern plume water and the tank water. In the

second experiment the southern plume and the northern plume have the same densities

and, as would be expected, there is a single layer of both northern and southern plume

water with a shallow mixed layer between it and the ambient tank water. In the third

experiment we see the opposite of what was observed in experiment 1. There is a

northern plume water overlying southern plume water. The fifth experiment shows a

similar structure to the third. The difference between the measured densities of the three

water masses and the densities of each layer in the profile could be due to problems

during probe calibration. The fourth experiment has a slightly different structure. From

the profile it appears that there is a mixed layer with a linearly decaying density overlying

a layer of southern plume water. A similar structure is observed in the sixth experiment

however, the density profile in the upper layer is not quite linear. In both cases it is

possible that the probe did not come out of the water and may have missed a thin layer of

northern plume water that may have existed at the surface of the water.

Expedment

1

II

I

I

F

l

l

I

Ki

I

I

S

I

I

I

I

I

2

Experiment

I

I

I!

~I

I.

0.995 1

I I

_

I

It

lu

Ii

*

I

I.

I

.005 1.01 1.015102

I

1.02

Experiment

3

0.R

1

*

Ji *I

I

I

10051.01 1.0151.02 1.0

Expement 4

-2

4

EI

0~5

1

1.0051.01 1.015

Expeiment

5

Experment 6

25

35

Figure 3-3 Density profiles from each experiment taken closest to the wall of the tank.

Density is in g / cm3 and the y-axis represents the distance from the top of the profile in cm.

3.3.3 Mixing

To determine the amount of mixing occurring between the plumes after interaction the

Richardson number was calculated for each experiment. The Richardson number is defined as

- g

Ri = h,,,

where h, is the measured thickness of the mixed layer between the northern and southern plumes

and

Ugx

=ghpx

is the geostophic velocity calculated for each plume and

h

2Qxf

is the theoretical depth of each plume at the side of the tank. It is usually assumed that for Ri << 1

mixing is important. The values for h,, h,,, u, and Ri for each plume for all six experiments can be

found in table 3-2.

Exp

1

2

3

4

5

6

hm (cm)

1

0

0.55

1.75

0.9

1.5

hpn (cm)

3.24

2

1.41

4.48

1.32

1.37

hps (cm)

2.01

2

1.96

2.01

1.97

1.42

ugn (cm/s)

1.76

3.16

3.77

2.11

5.5

5.41

Ugs (cm/s)

3.15

3.16

3.2

3.15

3.19

2.65

Ri

2.04

0

8.14

6.4

2.98

3.25

hm* (cm)

0.5

0

0.07

0.27

0.3

0.46

Table 3-2 Summary of important parameters used to estimate the importance of mixing between the

northern and southern plumes.

In the second experiment the two plumes had the same buoyancy flux after interaction the

plumes are indistinguishable from each other and therefore no Richardson number can be calculated.

In all of the other experiments the Richardson number is considerably greater than one. To see how

sensitive the Richardson number is to changes in the measured value of mixed layer thickness, the

mixed layer thickness for a Richardson number of 1,

h,,, = abs

•

-

)

was calculated. In figure 3-4 the upper and lower bounds of the measured mixed layer are indicated

by green lines. The upper and lower bounds based on the mixed layer thickness predicted for cases

in which the Richardson number is equal to one are represented by red lines. As can be seen for all

experiments the mixed layer thickness for the case of Ri = 1 is considerably smaller than the value

measured and from the shape of the profiles it is not possible to define the mixed layer using those

bounds. Assuming that our equations are appropriate for plume interactions we can infer that mixing

is relatively unimportant between the southern and northern plume.

EpeqOrimnt

1

fll

I

I

I

I

I

I

K

*1

I

I

1

1

1

0

1

1

' I

1.19 1.• 10I 1.0

1.018

1016 1.017

101

Expeime

4

Eqeiment 3

S

i

I

I

1

I

" I

I ·I

401

mh

2W

2M

a-

a

1.018

1.02

1.0I

4 1. . 1.01

1. 0141.014

1.0161.0181.02

1.014

1.011,012

Expefiment6

2W-

I

-

I

Exp

I 5

I

n

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

401

2W0

2M

n

0.U

-I

1

I

1.05

p1

I

1.01 1015

1.02

I

I

1 21 1

I

I

I

I

1.022

1014 116 1018 1.02

1 1 01

Figure 3-4 Comparison of measured mixed layer thickness between the northern and southern

plumes and the mixed layer thickness predicted for a Richardson number of one.

The same process was repeated for the mixed layer between the lower plume (northern or

southern depending on the experiment) and the ambient water. Since the ambient water was

motionless the equations for the Richardson number and mixed layer thickness for Ri = 1 simplify to

the following

Ri =

h,g'

2

Ug

h,,. =abs 9

where h,,,,

h, and ug are all calculated for the lower plume. The values for these parameters can be

found in table 3-3. In all of the other experiments the Richardson number is less than one.

Experiment

1

2

3

4

5

6

hm (cm)

0.6

0.9

1

0.65

0.7

0.65

hp (cm)

2.01

2

1.41

4.48

1.32

1.37

ug (cm/s)

3.15

3.16

3.77

2.11

5.5

5.41

Ri

0.3

0.45

0.71

0.15

0.53

0.48

hm* (cm)

2.01

2

1.41

4.48

1.32

1.37

Table 3-3 Summary of important parameters used to estimate the importance of mixing between the

lower plume and the ambient water.

In figure 3-5 the upper and lower bounds of the measured mixed layer between the lower

plume and the ambient water are indicated by green lines. The upper and lower bounds based on the

mixed layer thickness predicted for cases in which the Richardson number is equal to one are

represented by red lines. As can be seen for all experiments the mixed layer thickness for the case of

Ri = 1 is considerably larger than the value measured which leads to the conclusion that most of the

mixing occurs between the plumes and the ambient water.

Eperinmel

Experient2

II

I

-

I

I

II

I

I

I

I

U1014

1.01

1.01

1.018

1.I .I

1016 1.011.018

1,014

1.015

1019 1.02

Eqeero 3

Eperiment4

fill

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

IL-

MO

t

2M

0

I

I

I

I

II

1,011.012

1.014

1.016

1.0181.02 1.

I

I 1

1. 1.04

1 l. 1.01

1.012

1.014

1.016

1.018

1.02

Expeiment5

Experiment6

imi----__

[

I

I

i

I

LI

0.99 1

I

1.5

1.01 1.0151.02

1.02 1.0

4

1. 11 1.012 1.014

1 .0161018

1.02

1022

Figure 3-5 Comparison of measured mixed layer thickness between the northern and southern

plumes and the mixed layer thickness predicted for a Richardson number of one.

3.4 Summary and Discussion

In this chapter I try to quantify mixing between two river plumes through a series

of laboratory experiments modeling the interaction of two plumes with various densities

and flow rates. Based on these experiments it appears that much of the mixing occurs

between the plumes and the ambient water and that mixing is relatively unimportant

between the southern and northern plume. However, the profiles in these experiments

were taken downstream of the southern source and it is possible that mixing could be

occurring upon the initial interaction of the two plumes and has subsided by the time they

reach the location where the profile was taken. Therefore, from these experiments we can

conclude that, under these idealized conditions, if the A. fundyense did not enter the

second plume near the source they would have to find another way to enter the second

plume. One possibility is through their light seeking swimming behavior.

Chapter 4

Physical Model

Again consider a case where one river plume, carrying A. fundyense, travels along

the coast and comes into contact with a southern river plume without A. fundyense. This

time, the first plume is denser than the second and is therefore not likely to go above the

second plume but will probably go beneath it or around it. It is possible for A. fundyense

to enter the second plume, and then gain access to the coastal shellfish beds, through

vertical swimming. However, for this to be effective the first plume must go beneath the

second plume. If the northern plume is unable to go beneath the southern plume then the

coast might be protected from the A. fundyense and an outbreak of red tide. Using a series

of numerical model runs I investigate the effects of the southern plume on the path of the

northern plume and attempt to specify under what conditions the northern plume will be

subducted beneath the southern plume.

4.1 Model Formulation

In this work a simple 2 '/2 layer model is used to study the interaction of two river

plumes propagating along the coast in the direction of Kelvin wave propagation. Here the

basic model formulation is described. In the following equations the subscript s denotes

the top layer which originates from the southern river, n denotes the middle layer which

originates from the northern river, and 0 denotes the bottom layer or the ambient ocean

water. We assume that the pressure in the fluid is hydrostatic and, within each layer, the

horizontal velocity is independent of depth. The pressure within each layer can then be

written as

+h -z)

+h,

p, =gp (h,

p, = gpsh, + gp,(h, + ho - z)

Po = gPsh, + gph,+gPo (ho - z)

where p,, Px and hx are the pressure, density and thickness of the xth layer

respectively. Assuming that there is no horizontal pressure gradient in the bottom layer

the depth of the bottom layer can be written as

ho

=

_

h -

h,

Po

Po

Using this new definition for ho the equations for pressure can be simplified to

PS

Po - Ps hi

p,

PI, p h+ Po - P

Pn

Pn

Po - P

PO

h-z

Po

Po = -gz

If we set p, = (1- 6,)Po and p, = (1- 6,)po, the first two equations become

s= 6Sgh, + 6,gh, - gz

PS

g

hS +6h

16n

z

1-6n

with the Boussinesq approximation, the second equation simplifies to

P-

gs,h +gS,h, - z

Pn

The horizontal pressure gradients can therefore be written as

1

-Vp,

Ps

1

=

IVp,

gbsVh, + g6,Vh,

g6,Vh, + g6,Vh,

Pn

For the model we can now use the Bernoulli form of the momentum equations

U + (f +

x u = -VB

at

wheref is the coriolis parameter,

av

ax

au

ay

and the Bernoulli function is

B=P

p

(+1 2 +2)

2

The mass conservation equations for the model are

_w

VVW:F-=

0.

h

The model domain consists of a 25km x 300km rectangular basin. Fresher water

is discharged uniformly (in y and z) at the coastline from two rectangular river mouths, of

length L, and depth hr,, centered at a distance of 296km and 256km from the southern

end of the domain. The base case was run at both a .25km resolution in x and y with a 1

minute time step and .5km resolution in x and y with a 2 minute time step. No qualitative

differences were evident so for the rest of the runs the lower resolution was used.

All model runs presented neglect the influence of tides, winds and bottom friction.

Mixing is also neglected in the numerical model partially due to the experimental results

described in the previous chapter but also to keep the model as simple as possible. The

coriolis parameter fis set to 10- 4 s-' and the ambient ocean water remains motionless and

3.

maintains a constant density po of 1020 kg / m'm

In section 4.2 the base case and initial analysis is presented. In section 4.3 the

effect of the river mouth geometry is investigated. In these runs all parameters remained

constant except the river mouth lengths and depths. The following ranges were used for

both river mouths: depth of the river mouths 2 m < h, < 14 m , length of the river

mouths 1 km < Lr < 7 km . In section 4.4 the effect of varying river fluxes is investigated

by keeping everything constant except the flux of each river which was varied within the

range 1250 m3 / s < Q < 10,000 m 3 / s.

4.2 Base Case

As a base case (run I in table 4-1) we consider two almost identical river inflows.

Both have a river mouth 2 m deep and 1 km wide and a flux of 1250 m3 / s. The

difference between the two rivers is their densities. The density of the northern river ( p,)

is 1015 kg / m3 and the density of the southern river ( p,) is 1010 kg / m3 .The difference

in density was necessary to create the 2 ½2 layer system, as described, with the northern

plume being the lower layer.

The thickness of the northern plume (h , ), thickness of the southern plume (hs)

and the total depth of river input (h, + h, ) after a period of 15 days can be seen in figure

4-1. Both river outflows initially form bulges and then turn right to form a coastal

current. After 15 days two bulges have formed which are wider and deeper than the

downstream coastal current which forms to the south of the southern bulge. It is also

evident from these plots that the southern bulge is diverting a significant portion of the

northern plume away from the coast.

The horizontal velocities for the northern and southern plumes can be seen in

figure 4-2 and figure 4-3 respectively. As seen in the figures, the coastal current is

unidirectional with southward velocities of approximately 5 cm/s in the northern fluid

and 10 cm/s for the southern fluid. The bulge regions are anticyclonic and appear to be in

cyclostrophic balance. The maximum velocities in the bulge regions are 10 cm/s for the

northern bulge and 25 cm/s for the southern.

0

5

10 15

x(km)

20

5

10 15

x(km)

20

0

5 10 15 29

x(km)

Figure 4-1 The thickness of the northern plume (h,), thickness of the southern plume

(h, ) and the total depth of river input (h,, + h, ) after a period of 30 days are shown from

left to right (m) for the base case.

w1

06

05

0.4

03

02

01

.15

0l

~-

-

-

--

"

Figure 4-2 Depth (m) and horizontal velocities (m/s) for the northern plume.

06

105

04

-0.05

03

-0.1

0.2

01

0

.25

01

.3

111

0.36

10

20

30

40

50

Figure 4-3 Depth (m) and horizontal velocities (m/s) for the southern plume.

In Fong & Geyer (2002) it was discovered that in the absence of an ambient

current the bulge would continue to expand. In this model the rivers are flowing into a

motionless ocean so it wouldn't be unreasonable to assume that each bulge would

continue to grow in the absence of an ambient alongshore current. A growing southern

bulge could significantly affect the distribution of any pollutants or organisms originating

in the northern plume. As previously mentioned, in this base case the southern bulge

seems to divert the northern plume away from the coast. If the plume continued to grow it

is possible that it could shield more of the coast from the northern plume and anything it

may be transporting. In figures 4-4 and 4-5 the depth of the northern and southern plumes

as they vary in the cross shore direction at the latitude of their respective river mouths can

be seen at one day intervals for 30 days. (Note that in figure 4-4 the plume seems to

thicken which is probably due to a wall effect). As can be seen the depth of the northern

bulge continues to vary whereas the depth of the southern plume begins to converge. It

appears that when the northern plume comes into contact with the southern plume it acts

to control the growth of the southern bulge like the ambient current controlled the single

plume bulge in the model used by Fong and Geyer (2002). So at least in this base case, it

seems that that the southern bulge would shield the same section from the northern plume

over time.

I

I

I

Northern Plume

I

•

'

I

-0.2

E

~-----~--c7-.

~--c*

--L

-~---e

--

-0.4

--

:s

E

,

c-

`-·=--~-sz---.

-~c~C~C14~

'4-;;ts

-0.6

E

-0.8

E

-1.2

-

-1.4

-

-1.6

-

-1.8

-

I

I

I

I

--

--

I

I

I

I

I

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

-

0

50

x (km)

Figure 4-4 Change in the width (cross shore direction) of the northern bulge region over

a thirty day period

Southern Plume

.- b

u

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-1

-1.2

-1.4

-1.6

-1 R

0

5

10

15

20

25

x (km)

30

35

40

45

50

Figure 4-5 Change in the width (cross shore direction) of the southern bulge region over

a thirty day period.

4.3 Variations in River Mouth Geometry

As seen in the base case the southern bulge can affect the path of the northern

plume as it progresses along the coast. Fong and Geyer (2002) found that the shape of the

bulge in the single plume was found to depend mostly on the velocity of the river inflow

and the width of the river mouth. A large velocity and narrow river mouth resulted in a

bulge which extended farther offshore. In this set of numerical experiments the width Lr

and depth h, of both river mouths is varied in an attempt to alter the horizontal size of

both the northern and southern bulges. The fluxes of both rivers remain the same for all

runs (Q,,,

Q= 1250

m3 / s ) . By holding the fluxes constant the velocities of the rivers

will increase as river mouth size decreases. Both an increase in river outflow velocity and

a decrease in river mouth size should act to increase the horizontal extent of the bulge.

However, it is not certain a priori whether variations in river mouth size will have an

effect on horizontal bulge size in the two plume case, especially in regards to the southern

bulge which seems to be affected by the northern plume. In this set of experiments I

attempt to discover if variations in river mouth size have any effect on bulge size and the

effect of these variations on the path of the northern plume. A summary of the

experiments can be found in table 4-1. All numerical runs were analyzed after a period of

thirty days.

Run

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

hrn (m)

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

14

14

14

14

14

14

hrs (m)

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

14

14

14

14

14

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

Ln

(km)

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

Ls

(km)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

un (mis)

0.63

0.63

0.63

0.63

0.63

0.63

0.63

0.16

0.07

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

us (m/s)

0.63

0.16

0.07

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.07

0.16

0.63

Rn

6.250

6.250

6.250

6.250

6.250

6.250

6.250

0.781

0.231

0.098

0.050

0.029

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

Rs

6.250

0.781

0.231

0.098

0.050

0.029

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.018

0.029

0.050

0.098

0.231

0.781

6.250

Rn/Rs

1.0

8.0

27.0

64.0

125.0

216.0

343.0

42.9

12.7

5.4

2.7

1.6

1.0

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.1

0.0

0.0

Table 4-1 Variations in river mouth geometry

Looking at plots of the northern plume thickness (h,), the thickness of the

southern plume ( h, ) and the total depth of river input (h, + h, ) for all of the runs there

appears to be two different qualitative results. For the majority of cases (runs 1-17) the

northern plume detached from the coast near the location of the southern bulge. In runs

18 and 19 the northern plume remained connected. The plots of the northern plume

thickness ( h, ), the thickness of the southern plume (h, ) and the total depth of river input

( h, + h, ) for run 17, representing the first case, and run 18, representing the second case,

can be seen in figures 4-6 and 4-7 respectively. In figure 4-7, it can be seen the maximum

depth of the southern plume is approximately 0.6 m; this is probably the reason that the

northern plume was able to remain attached to the coast and is not a very realistic case.

1.5

6E

>1

0

5

10

15

x*m)

20

5

10

15

x(km)

20

0 5

10 15 20

x(m)

Figure 4-6 The thickness of the northern plume (h,,), thickness of the southern plume

(h,) and the total depth of river input (h,, + h, ) after a period of 30 days are shown from

left to right (m) for run 17.

U

5

10

15

x(m)

2J

5

10

15

x(km)

J

U 5

I

15

I

J2

x(km)

Figure 4-7 The thickness of the northern plume (h,), thickness of the southern plume

(h, ) and the total depth of river input (h, + h, ) after a period of 30 days are shown from

left to right (m) for run 18.

The Rossby number, defined as

R =

Ur

fZr

where u,. is the velocity at the river mouth, has been found to best characterize the shape

of the bulge in the case of the single plume (Fong and Geyer, 2002) so, in an attempt to

quantitatively describe the effect of variations in river mouth geometry on the path of the

northern plume, the Rossby numbers were estimated for each river mouth. Since the size

of both river mouths was varied the ratio of the northern Rossby number and the southern

Rossby number was also calculated. To estimate the extent to which the northern plume

is deflected away from shore, the location of the center of mass of the northern plume at

the latitude of the southern river mouth is calculated. The distance between the coast and

the center of mass of the northern plume for various Rossby number ratios is shown in

the three plots in figure 4-8. The middle graph shows runs which all had an R, of

approximately 0.018. variations in R, under these conditions did not seem to alter the

location of the center of mass of the northern plume. The top graph shows runs which all

had an R, of 6.25 but varying R, values. For lower R, values which indicate a low source

velocity and a large river mouth, the Rossby ratio is higher and the distance between the

center of mass of the northern plume and the coast increases. The bottom graph shows

runs which all had an R, of 0.018 but varying R, values. Variations in R,, gave similar

results as those described for the runs with an R, of 6.25. It appears that for lower R,

values the southern bulge does not extend as far off shore but becomes thicker and it

therefore seems that the thickness of the southern bulge has an impact on the path of the

northern plume.

Rn=6.25

5•'

t

23.

-

23 1

22.

E 22.5-

21.521 -

20.50

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

250

300

350

400

RnlRs

Rs=0.018

B.

*

20 E

m 10

50

0

50

100

150

200

RnlRs

Rn=0.018

.

20-

E

'4*

15 -

C

! 10 5-

0

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

RnlRs

Figure 4-8 Comparison between the ratio of Rossby numbers for both river mouths and

the distance between the coast and the center of mass of the northern plume near the

southern river mouth

4.4 Variations in River Fluxes

The following numerical experiments were used to explore the effect of variations

in both southern and northern river fluxes on the path of the northern plume. In all of

these runs the southern and northern river mouths are 3 km wide and 6 m deep. The flux

of the northern and southern rivers vary within the range of 1250 m3 I s < Q < 10,000

m3 / s . The variation results in a change in velocity at the river mouths and therefore a

change in the Rossby numbers for each river plume. A summary of the experiments can

be found in table 4-2. Since the model has periodic boundary conditions, when the

southern river reaches the southern end of the domain it will then reappear at the northern

end. Due to the greater fluxes in these runs, the southern plume reached the southern end

of the domain in a much shorter time period so all of these numerical runs were analyzed

after a period of only twenty days. Some wrap-around still occurred, but we hope did not

impact the results.

Run

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Qn

1250

1250

1250

1250

2500

2500

5000

5000

7500

7500

7500

7500

10000

10000

Qs

2500

5000

7500

10000

1250

7500

1250

7500

1250

2500

5000

10000

1250

7500

un (mis)

0.07

0.07

0.07

0.07

0.14

0.14

0.28

0.28

0.42

0.42

0.42

0.42

0.56

0.56

us (mls)

0.14

0.28

0.42

0.56

0.07

0.42

0.07

0.42

0.07

0.14

0.28

0.56

0.07

0.42

Rn

0.231

0.231

0.231

0.231

0.463

0.463

0.926

0.926

1.389

1.389

1.389

1.389

1.852

1.852

Table 4-2 Variations in river fluxes

Rs

0.463

0.926

1.389

1.852

0.231

1.389

0.231

1.389

0.231

0.463

0.926

1.852

0.231

1.389

RnlRs

0.5

0.3

0.2

0.1

2.0

0.3

4.0

0.7

6.0

3.0

1.5

0.8

8.0

1.3

In terms of whether the northern plume separates from the coast due to the

southern bulge, all of the runs fit into three categories based on their Rossby number

ratio. In all of the runs with R, / Rs < 0.6 the northern plume separated from the coast at

the location of the southern bulge. In runs with R, / Rs> 1 the northern plume was able to

pass directly under the southern plume. For the two cases where Rn / Rs was between

these values part of the plume was able to go under the southern bulge but most of the

plume went around the bulge. Plots of the northern plume thickness (h,), the thickness of

the southern plume (hs) and the total depth of river input (hn + h, ) for runs 6, 8, and 10

are shown in figure 4-9, 4-10 and 4-11 respectively. Run 6 is an example of the first

regime with Rn / R,<0.6, run 8 is an example of a case where 0.6 <R,, / R,<1 and run 10

is an example of a case where R, / R,> 1.

0

5

10 15

x(km)

20

5

10

15

x(km)

M0

0 5 10 15 20

x(km)

Figure 4-9 The thickness of the northern plume (h,, ), thickness of the southern plume

( hs ) and the total depth of river input (h,, + hs ) after a period of 30 days are shown from

left to right (m) for run 6.

0

5

10

15

20

5

10

15

20

0

5 10 15 20

Figure 4-10 The thickness of the northern plume (h, ), thickness of the southern plume

( h ) and the total depth of river input (h,, + h, ) after a period of 30 days are shown from

left to right (m) for run 8.

0

5

10

15

x~n)

20

5

10

15

I(km)

20

0

5

10 15 20

x(km)

Figure 4-11 The thickness of the northern plume (h,), thickness of the southern plume

(h, ) and the total depth of river input (h, + hs ) after a period of 30 days are shown from

left to right (m) for run 10.

To quantitatively compare the effect of flux on the path of the northern plume we

again compare the Rossby ratio of each run to the distance from the coast to the center of

mass of the northern plume at the latitude of the southern river mouth (figure 4-12). For

small Rossby ratios the distance of the center of mass of the northern plume from the

coast increases quickly as the ratio approaches zero. For Rossby ratios greater than one

the distance is approximately 12 and 18 km.

0