Preface

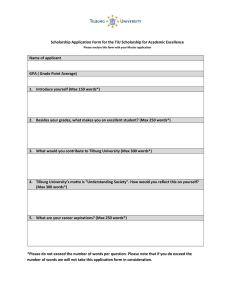

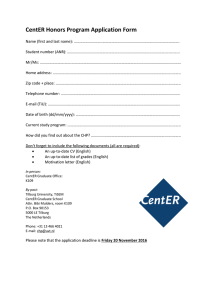

advertisement