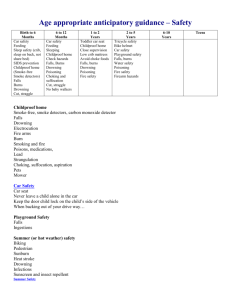

Child and adolescent Child and early adolescent drowning deaths in developing communities:

advertisement