Document 10679467

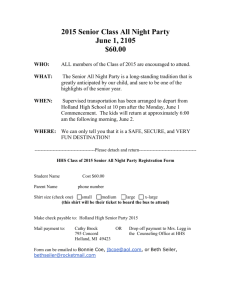

advertisement