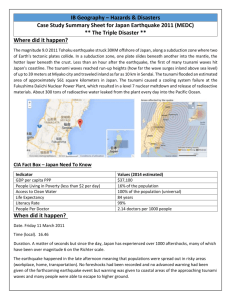

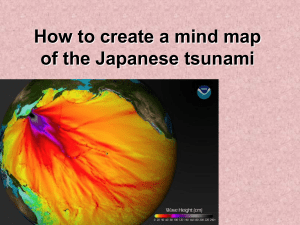

The March 11, 2011, Great East Japan (Tohoku) Earthquake Introduction

advertisement