'0

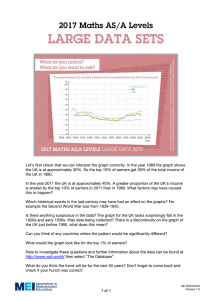

advertisement