The Rimrock Report

advertisement

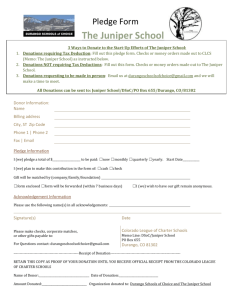

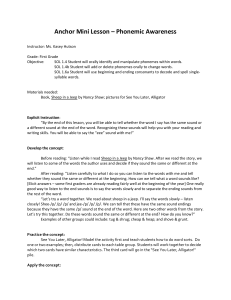

The Rimrock Report The University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources and the Environment January 1 2010 Volume 3, Issue 1 Introducing “Blue Collar Plants”: a plant collection and web page for the rest of us. Imagine if you will a physical description of you at the age of 18. You are hitting your prime years, men are at their peak, or nearly so. A description may include height, weight, hair color and eye color, much like the information on our drivers’ license. A more detailed description may go into the length of hair, if the hair is straight, wavy or curly. If the hair is described as curly is it a tight curl or a loose curl. Hi, this is John Kava, pinch hitting for Doug Tolleson. Now that you have revisited and embellished your youth, ask yourself, “does that description still apply today?” Unless you are still 18, chances are it doesn’t come very close. As we age, things change. Hair changes texture, color and may disappear all together! The size of blue jeans we wore at 18 have increased in size with our waist. Our weight has also changed, some more than others, but change occurs. One old timer once told me he had chest of drawers disease. Not the furniture. His chest had fallen into his drawers! Inside this issue: Introducing “Blue Collar 1 Plants”: a plant collection and web page for the rest of us. Johns Plant of the “week” 4 “TOP 10” PICTURES FROM 6 THE RANGE PROGRAM 2009 THE VIEW FROM THE RIM 6 JUST ME TALKING 6 What if I had a picture of you in your prime, without a written description? Say a prom picture or maybe your wedding photo. Could I give that photo to someone that doesn’t know you to use to pick you out of a crowded room? If we added the written description would they be successful? If you have ever tried to identify an unknown grass using one of those botanical books, either descriptive or with photographs, you might understand how frustrating identification can be. Often in the field we don’t see grasses when they are “18”, however most botanical guides use photos or descriptions of 18 year olds. Some animal may have stomped or chewed a part off, or drought might have affected normal growth. Maybe the grass you find is done living and the seeds have fallen off and the one leaf that remains is split and eaten by insects. Can it be identified? Some of you probably can’t think of a reason why you would want to identify a plant in this state, but as a researcher there are times we need to know the exact species of plant we find within our monitoring frame at any time of the year, not just at the peak of the season. Sometimes plant communities are used to determine condition of a rangeland site. A ranch or resource manager may need to identify a toxic plant or determine which forage species is most utilized. Bottom line, in the range profession, the ability to identify plants all year long and in varying degrees of growth or utilization is highly important. A program or website that allows one to identify plants with minimal effort would be a great value. “the ability to identify plants all year long and in varying degrees of growth or utilization is highly important.” The Rimrock Report Introducing “Blue Collar plants”...continued So, finding ourselves as frustrated as the rest of you non botanists, we decided to do something about it. We are collaborating with the Yavapai Master Gardener program to develop a “blue collar” plant collection and search engine. Blue collar plants, what does that mean? Dr. Doug Tolleson says it is a collection of plants “with their working clothes on.” Simply stated our goal is to provide a collection of photographs and collected specimens of the species of plants found in our area, “with their working clothes on”, to be used by the public to identify plants of interest. We don’t want to fill pages with botanical terms or descriptions of parts of plants as viewed through a microscope. We hope to provide enough information and details to allow you to match what you see in the pasture, meadow or forest to a name and description. Photographs are taken in the field with careful consideration to capture identifying characteristics of each plant as up close as possible. The botanical terms have been replaced with simplified definitions (words we normally use). Before unveiling this new tool, I want to provide a little history of how this all came about and give credit to those involved. When Dr Doug and I approached the Yavapai Master Gardeners in the summer of 2008 for assistance, they were already working on a collection of photos for trees and shrubs to assist the volunteers working the phone help line at the extension office. They currently have 65 trees and shrubs cataloged. Their goal is to provide an easy way for the volunteers to determine the species the caller was talking about through the use of photographs and common word descriptions. They were more than willing to join forces and start adding grasses to their collection and database. To date we have added 76 grass species! The number of species and photos per species will continue to grow, in particular showing plants at different times of year and after grazing has occurred. The team leader for this project is Master Gardner, Sue Smith. Sue has done some plant collecting and captured grasses with her camera, but she is most appreciated for her ability as a database developer. She developed the website from the ground up. Debbie Allen, another Master Gardner has contributed to the project by collecting grasses in and around Prescott, mounting and identifying them. It has taken many hours in the field and at a computer to get to the point we are at today. So after many months of collection, organization, disorganization, meetings, photographing, a little push from Dr Doug (i.e. “git-r-done”), cooler weather to keep us all indoors, and the rumination of ideas that began over a year ago, we are ready to make available to the public, the fruit of our labor. I feel the best way to judge the value of a tool is to go and use it, so here is the URL for the website http:// yavapaiplants.info or click here Blue Collar Plants. We have also put together a short video tutorial. If you are still reading, here are a few tips on navigating the web site. Once on the main page, move your cursor over “Search Grasses” and click. This will take you to the Search page. At this point you may enter info by clicking on a button or using a pull down menu and making a selection. You can select one characteristic or multiple items. When you click on the “Submit Query” button at the bottom of the page, the results will be displayed on the right hand side of the page. If you don’t select any characteristics, all grasses will come back as a match. If too many records are returned you might try adding another characteristic to the search to narrow the number of matches. Once you have narrowed the number of records returned to a few, you can click on the picture and go to the grass description page. The grass Page 2 The Rimrock Report Introducing “Blue Collar plants”...continued description page will open in a new tab or window. If that particular plant does not match the one you are trying to identify, simply close that tab or window to return to the search results. You can then look at the other grasses that may match the one you are trying to identify. I suggest using the “leaf arrangement” and “seedhead structure” radio buttons as your first search criteria. The small illustrations next to the buttons are helpful to get started. If this does not narrow the search enough, you may click on the words “Click here for More Search Options” and you will be provided more detailed options to include in your search. As the name implies, this project was not just an academic exercise to entertain ourselves; we built this tool to be used. We certainly will use it, but we especially hope that you will too. If you find value in this tool or have suggestions on how to improve it, we would be happy to hear from you. Please contact me at: jakava@cals.arizona.edu. Click here to see our top pictures for the V Bar V range program in 2009 One of the helpful illustrations on the search page to guide you in proper identification of grasses. Page 3 Volume 3, Issue 1 John’s Plant of the “week” By now you know that John and I have switched places for this issue. Or maybe you don’t… maybe ya’ll are all a bunch of “plant junkies” that usually go straight to this article anyway. Oh well, I thought of several plants to write about; sideoats grama, saguaro, catclaw acacia, etc… and finally decided upon alligator juniper (aka, JUDE2 or Juniperus deppeana for all you plant-teamers). I have come to really like these trees since moving out to Arizona two years ago. Maybe it is because, in the immortal words of John Waynea, “…they remind me of me…” They are not too much to look at, usually all bent, scarred, and gnarly, off by themselves, but they just seem to hang in there. Maybe it is because of where you find them. Around here, the country with alligators is my favorite; mid-elevation savannah, transition to the pines, rough, rocky, hard to get to, fewer people, some problems and/or challenges to deal with, but lots of plant diversity, lots of critters… Whatever the reason, here are a few facts and figures for you. The following are selected excerpts from the USDA Forest Service Fire Effects Information System web site: Alligator juniper occurs from western Texas to northwestern New Mexico and reaches its northern limit in north-central Arizona near Flagstaff b. It extends southward into northern and central Mexico where it is described as "widespread". Alligator juniper is the largest southwestern juniper, but most commonly grows as a medium-sized evergreen tree that reaches 20 to 40 feet (6.1-12.2 m) at maturity. It can attain heights of up to 65 feet (20 m) and maximum diameters of 7 feet (2.1 m). A single short but heavy massive trunk is more typical than multiple stems. The plant receives its name from the thick, checkered, furrowed bark which is divided into scales resembling the back of an alligator. Mature alligator junipers often have a large portion of dead wood intermixed with living wood. Alligator juniper most commonly grows between 4,000 and 6,000 ft (1,220-1,830 m). Alligator juniper occurs in pinyon-juniper (Pinus-Juniperus spp.), pine-oak (Pinus-Quercus spp.), juniper-oak, Madrean evergreen, and riparian woodlands, and in ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa) forest. It rarely grows in dense stands. Typically, it occurs in small groves or as individuals interspersed with other junipers, ponderosa pine, oaks, or various understory species. Tree species commonly co-dominating with alligator juniper include pinyon, oneseed juniper, ponderosa pine, and gray oak. Common shrub associates include skunkbush sumac (Rhus trilobata), true mountain-mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus), desert ceanothus (Ceanothus greggii), pointleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos pungens), Apache plume (Fallugia paradoxa), and Parry agave (Agave parryi). Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), sideoats grama (B. curtipendula), vine-mesquite (Panicum obtusum), wolftail (Lycurus phleoides), bottlebrush squirreltail (Elymus elymoides), mountain muhly (Muhlenbergia montana), pine muhly (M. dubia), and bullgrass (M. emersleyi) are frequent grass associates of alligator juniper. Alligator juniper hybridizes with oneseed juniper (J. monosperma) from central Mexico through the Southwest to southern Colorado. Redberry juniper (J. pinchotii) is a stabilized hybrid of alligator juniper and oneseed juniper. (I did not know this…) Wood of alligator juniper currently has little commercial value. (But…) Alligator juniper can be made into particleboard and is occasionally milled as lumber. The wood is also used to make furniture. It is most commonly used to make various novelty products such as bookends, lamp bases, or small chests. Alligator juniper wood is fragrant with an attractive color and grain. Alligator juniper makes excellent firewood of relatively high heat value. The wood is light, easy to split, and burns with a pleasant aroma. It provides an estimated 243,000 BTUs/foot 3. Page 4 The Rimrock Report Alligator juniper cone-berries are believed to be an important component in winter wild turkey diets in north-central Arizona. Cone-berries may be particularly important to wild turkeys during drought years. The prevalence of juniper cone-berries may determine the densities of overwintering birds such as the Townsend's solitaire, western and mountain bluebirds, and the American robin. The foliage of alligator juniper is apparently somewhat more palatable than the foliage of most other junipers and, consequently, is more often utilized as browse. Research indicates that the mean volatile oil content of alligator juniper is less than that of either Rocky Mountain or Utah juniper. Foliage is also believed to have less of an inhibitory effect on bacterial rumen of deer. The foliage of alligator juniper frequently represents a major item in elk diets in Arizona ponderosa pine stands. It has little forage value for most livestock but is sometimes eaten by domestic goats. Many pinyon-juniper ranges in which alligator juniper is well represented are now in relatively poor condition. Humphrey reports that blue grama, sideoats grama, Stansbury cliffrose (Purshia mexicana var. stansburiana), silktassel (Garrya spp.), and Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) occur commonly on alligator juniper ranges of Arizona in good condition, with the cover of such species as bottlebrush squirreltail, goldeneye (Viguiera spp.), birdbeak (Cordylanthus parviflorus), and broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae) increasing with overgrazing. The following species are indicative of range condition on some Arizona alligator juniper sites: excellent: black grama (Bouteloua eriopoda), Indian ricegrass, blue grama, winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata), Stansbury cliffrose, and fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens) good: Indian ricegrass, black grama, blue grama, needlegrass (Stipa spp.), and spike muhly (Muhlenbergia wrightii) fair: blue grama poor: broom snakeweed, ringgrass (Muhlenbergia torreyi) Somewhat variable results have been obtained following alligator juniper removal aimed at returning woodlands to grasslands to increase forage production. In some Arizona alligator juniper savannas, early grass production is as much as 4 to 5 times greater under the crowns of junipers than in the interspaces. Forage species such as mutton bluegrass (Poa fendleriana), bottlebrush squirreltail, prairie junegrass (Koeleria macrantha), and western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii) particularly benefit from the shade of large alligator junipers. Alligator juniper canopies are often high enough so that fires scorch but do not severely damage the crown. The bark also provides protection from fire.Alligator juniper is generally capable of prolific sprouting after aboveground vegetation is consumed by fire, particularly if the "resprouting zone" is covered by soil. By sprouting, alligator juniper may survive fires of even high intensity and quickly regains dominance on most sites. Mortality of even small trees generally appears to be low. Alligator junipers typically sprout from the root crown following fire. Susceptibility to fire may also be greater during drought years. So like many other plants, animals, or people; alligator junipers and the sites where they exist have their good points and bad points. Cows and elk seem to like them for shade, and I guess I agree. I have had some great lunches sitting under an alligator, sharing the solitude and enjoying the view. a As spoken by Rooster Cogburn to Ranger La Boeuf in one of the greatest movies of all time, True Grit (1969). b Map from USGS http://esp.cr.usgs.gov/data/atlas/little/ Page 5 The view from the Rim Any of you remember the scene in “Man from Snowy River” where Jim Craig rides down the mountain trying to catch the brumbies? Here is an excerpt from the original poem by Banjo Patterson in 1890 that inspired the movie… When they reached the mountain's summit, even Clancy took a pull, It well might make the boldest hold their breath, The wild hop scrub grew thickly, and the hidden ground was full Of wombat holes, and any slip was death. But the man from Snowy River let the pony have his head, And he swung his stockwhip round and gave a cheer, And he raced him down the mountain like a torrent down its bed, While the others stood and watched in very fear. He sent the flint stones flying, but the pony kept his feet, He cleared the fallen timber in his stride, And the man from Snowy River never shifted in his seat -It was grand to see that mountain horseman ride. Through the stringy barks and saplings, on the rough and broken ground, Down the hillside at a racing pace he went; And he never drew the bridle till he landed safe and sound, At the bottom of that terrible descent. Phone: 928-646-9113 x18 Fax: 928-646-9108 Cell: 928-821-3222 E-mail: dougt@cals.arizona.edu Web: http://cals.arizona.edu/aes/vbarv/ The University of Arizona School of Natural Resources V-V Ranch 2657 S Village Dr Cottonwood, AZ 86326 Note: Please email me if you would like to be added to the “mailing” list for this newsletter. Just me talking... Surely it is not already 2010. It seems like only yesterday we were getting ready to “party like it’s 1999”. It was the eve of “Y2K” and we were all going to die when our computers stopped at midnight… 1999 was my second year at the Gan Lab and we were just starting to branch out with fecal NIRS into things like detecting parasites or physiological status in grazing animals. It was pre-9/11, pre-PhD, I did not have a cell phone… Landmark years such as the turn of a decade or century cause us to look back at where we’ve been more so than in typical years. So, I took a look through the Journal of Range Management from 1999 to see if anything jumped out at me. Maybe because climate change, drought, rotational grazing, monitoring, and adaptive management have been on my mind, an article by Tom Thurow and Butch Taylor stood out (Viewpoint: The role of drought in range management. JRM 52:413–419). I especially thought this excerpt was applicable: “It is the responsibility of the individual rancher to be aware of how much forage is available and to anticipate current and future animal (livestock and wildlife) demand. Monitoring the extent of use on key vegetation species is a useful indicator of grazing pressure. By careful monitoring and control of grazing, the rancher can quickly identify and respond to the beginning of a forage deficit.” As usual, I would add to that statement that it is equally important for range and or ranch managers to be prepared for and ready to respond to adequate or above average precipitation/forage/fuel conditions as this will facilitate ecologic or economic gains that help offset the downturns. I know I am biased but I think the range profession is making strides in doing just that; I hope our efforts in the range program at the V Bar V will generate significant contributions. Speaking of which, we had another busy year at the V Bar V. Range Rocks! continues to gather momentum, Blue Collar Plants is up and running. Please give us feedback on this, we really want to produce a useable product for you. We have ramped up our fire related research, including the application of fuel modeling with data collected on tablet PC’s and VGS software. Diet quality work via fecal NIRS continues as does other portable NIRS projects (i.e. soil and plant C/N), we wrapped up the utilization on weeping lovegrass study, spent some time in Africa, went on the Hopi Range Trail Ride… but other than that we just sat around getting fat and lazy. The Aggies and Wildcats both went to bowl games. I’ll just leave it at that. Oh well, the autumn colors were pretty spectacular this year, even in the desert. Check out our “Top pictures” for more great Arizona scenery and some “action shots” from the V Bar V range program. Till next time… Doug Page 6