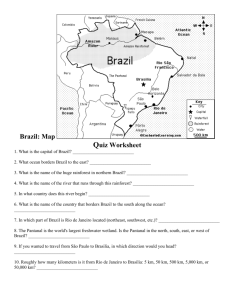

by 1961 Federal University of Rio de ...

advertisement