Document 10642322

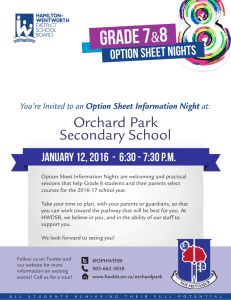

advertisement