(1965)

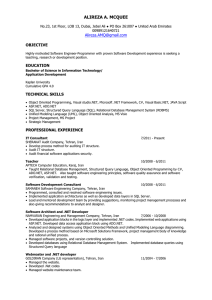

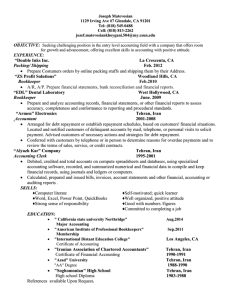

advertisement