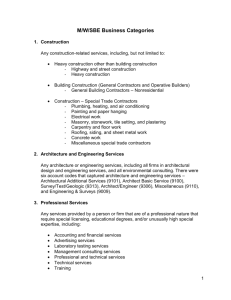

(1965) ASSISTANCE MINORITY CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTORS by

advertisement