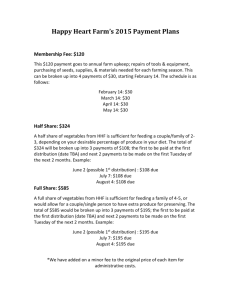

Changing Farm Structure and the Distribution of Farm Payments

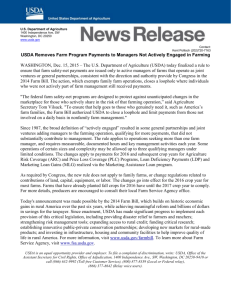

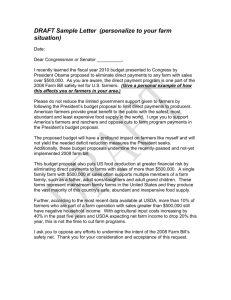

advertisement